According to Borges, copulation and mirrors are abominable in that they exist to multiply the number of men. Similarly, education and art are abominable in that they exist to multiply that part of man which is speech. And the speech they say is that they have said.

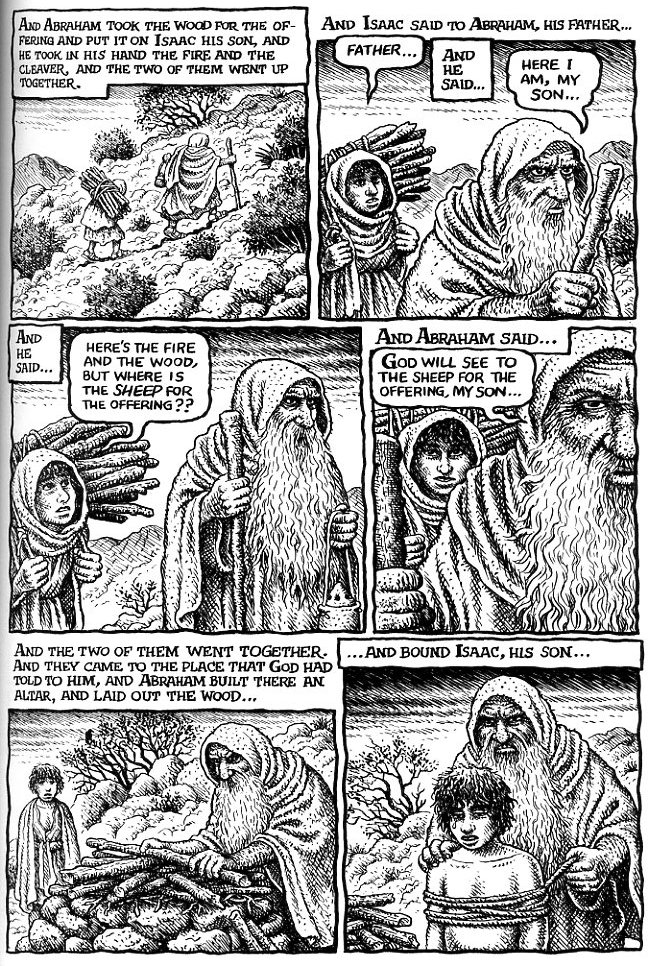

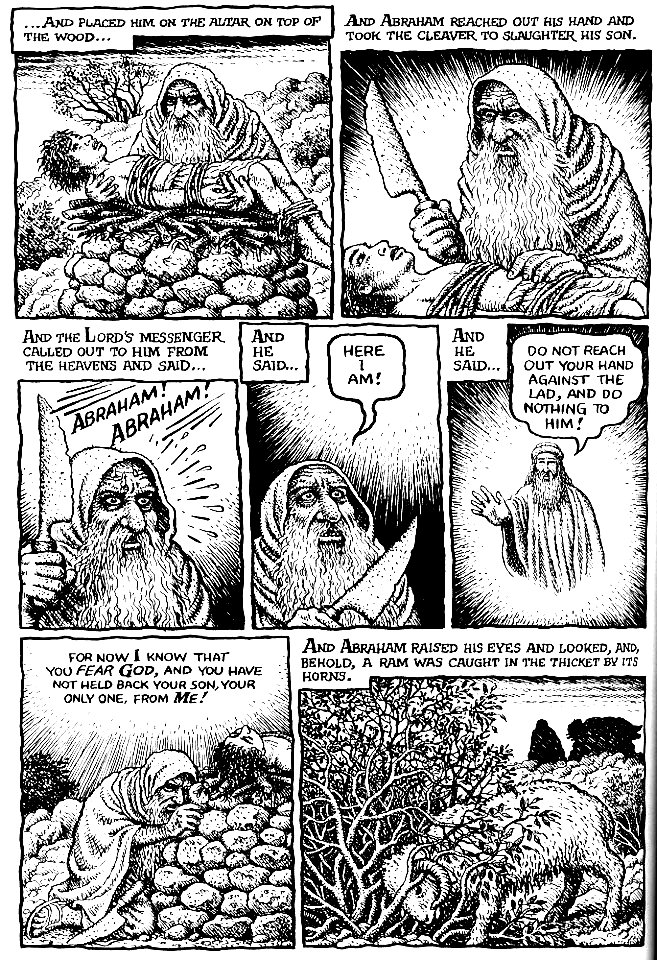

And it came to pass after these things, that God did tempt Abraham, and said unto him, Abraham: and he said, Behold, here I am. And he said, Take now thy son, thine only son Isaac, whom thou lovest, and get thee into the land of Mori’ah; and offer him there for a burnt offering upon one of the mountains which I will tell thee of. And Abraham rose up early in the morning, and saddled his ass, and took two of his young men with him, and Isaac his son, and clave the wood for the burnt offering, and rose up, and went unto the place of which God had told him. Then on the third day Abraham lifted up his eyes, and saw the place afar off. And Abraham said unto his young men, Abide ye here with the ass; and I and the lad will go yonder and worship, and come again to you. And Abraham took the wood of the burnt offering, and laid it upon Isaac his son; and he took the fire in his hand, and a knife; and they went both of them together. And Isaac spake unto Abraham his father, and said, My father: and he said, Here am I, my son. And he said, Behold the fire and the wood: but where is the lamb for a burnt offering? And Abraham said, My son, God will provide himself a lamb for a burnt offering: so they went both of them together.

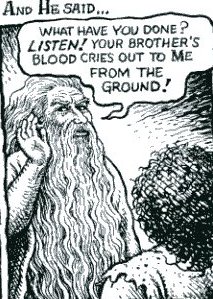

Isaac is asking to be educated; where is the sacrifice? Abraham replies with an answer that is no answer, “God will provide himself a lamb for a burnt offering.” The statement is true — God will provide the offering, though not in the way Isaac thinks. The statement is even more true — God will provide the offering, and exactly in the way that Isaac thinks. But the truth swallows itself. The answer is an irony when the reader sees it the first time, and a different irony when read through again. It does not so much cancel out as freeze; it conveys knowledge, but the knowledge it conveys is indeterminable. The point, in the end, is not what Abraham says, but that he says something — and “so they went both of them together.” Abraham teaches Isaac, God teaches Abraham, God and Abraham and Isaac teach us, and what they teach is a story of sacrifice; that there can be no sacrifice without a story. Isaac is bound before he is bound; his education delivers him to Abraham.

It was early morning. Everything had been made ready for the journey in Abraham’s house. Abraham took leave of Sarah, and the faithful servant Eleazar followed him out on the way until he had to turn back. They rode together in accord, Abraham and Isaac, until they came to the mountain in Moriah. Yet Abraham made everything ready for the sacrifice, calmly and quietly, but as he turned away Isaac saw that Abraham’s left hand was clenched in anguish, that a shudder went through his body – but Abraham drew the knife.

They turned home again and Sarah ran to meet them, but Isaac had lost his faith. Never a word in the whole world is spoken of this, and Isaac told no one what he had seen, and Abraham never suspected that anyone had seen it.

In this passage from Fear and Trembling, Kierkegaard imagines a different end of the Biblical narrative, an untold amendation. That untold amendation is silence — “Never a word in the whole world is spoken of this.” Kierkegaard’s poetry creates a loss that has no trace except the poetry; the words serve solely to mark the words that are not spoken. Isaac’s education is that his education is violence; the point of the knife separates language and meaning. The story is that the story is violence; it is Kierkegaard’s left hand that is clenched in anguish, his body that shudders, his right hand that draws the knife, and his word that is spoken to never be spoken. Innocence is sacrificed to art for the sake of some other; a God who does not speak in this text. The lack of speech is the story; a absence beneath which lies a secret. And that secret is no secret, an other that is no other.

If [Abraham] were to speak a common or translatable language, if he were to become intelligible by giving his reasons in a convincing manner, he would be giving in to the temptation of the ethical generality earlier referred to as that which makes one irresponsible. He wouldn’t be Abraham any more, the unique Abraham in a singular relation with the unique God. Incapable of making a gift of death, incapable of sacrificing what he loved, hence incapable of loving and of hating, he wouldn’t give anything more.

Derrida in The Gift of Death is here teaching us about Abraham. What he is teaching us is that there can be no teaching about Abraham. When Abraham becomes comprehensible, he ceases to be himself; he becomes a general Abraham. He might as well, then, be Isaac, who can give no gift of death, who sacrifices nothing, who cannot even be said to love or hate, for if his love and hate do not figure in the words of the story, where are they? Or he might as well be Derrida, who is paraphrasing Kierkegaard expanding on the Biblical story, and whose love and hate and faith and lack thereof disperse like smoke, a sacrifice of nothing to no Other. We don’t know Derrida or the meaning of Derrida, but we know his teaching. If he were to become intelligible by giving his reasons in a convincing manner, he would be giving in to the temptation of the generality. Then he might as well be Isaac, who has only the secret which Kierkegaard gives him, a gift of death which is nothing but Kierkegaard speaking.

And the angel of the Lord called unto Abraham out of heaven the second time. And said, By myself I have sworn, saith the Lord, for because thou hast done this thing, and hast not withheld thy son, thine only son; That in blessing I will bless thee, and in multiplying I will multiply thy seed as the stars of the heaven and as the sand which is upon the sea shore, and thy seed shall possess the gates of his enemies.

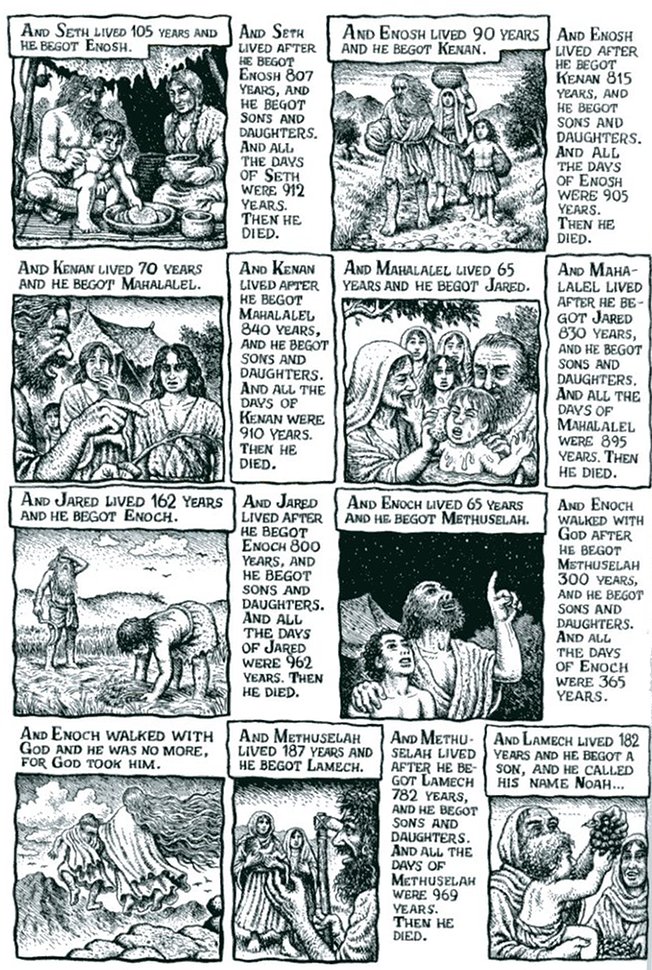

Derrida notes that God swears here by himself. What he promises is a repetition of the covenant he promised Noah: as Derrida says “a terrifying sovereignty, whose terror is at the same time felt and imposed by the human, inflicted on the other living things.” The gift of death multiplies; to offer nothing is to reap a story, another self made of words and desire. God says Isaac is “thy son,” Abraham’s love and Abraham’s seed . The sacrifice is the sacrificer. It is that which says, “Here am I.” When there is not Isaac, there is Abraham, or Kierkegaard, or Derrida, or me. Someone must ask, where is the lamb? How else could the answer be the answerer and the knife? Education and art say that Isaac was brought down from the mountain. But something was sacrificed there, a lamb or a ram. Or rather a nothing, a thing with no voice. God speaks for it. Then He devours its heart.

______________

This essay first appeared in Proximity Magazine #8, edited by Bert Stabler.