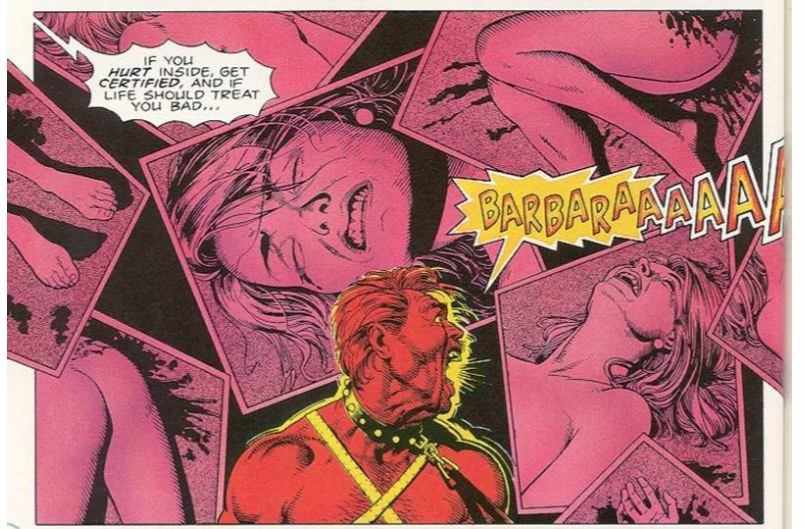

Whisper by Steven Grant and Rich Larsen

Far too long ago now, in the early ’90s when the comics business was fat & I worked on all sorts of books for all sorts of companies, I was a guest at a convention in Michigan. In a highly unorthodox move, the convention organized a “writing comics” panel & filled it with every comics writer in attendance, an approach that packed the stage with some 14 or 15 writers. The panel had no specific agenda, and when the introductions were over we threw it open to questions.

Inevitably, up piped someone – there’s always someone – who asked in a voice deeply embittered by the world’s failure to acknowledge his genius why, since so many comics are clearly crap, was he unable to get any editor anywhere interested in buying his stories instead of using the worthless shlubs they regularly used?

Obviously, none on the panel numbered among the tired, unimaginative, untalented hacks he was referring to. Obviously. (I should mention the non-exclusive emphasis of the panel, the show and his question was on work-for-hire superhero comics. Full disclosure and all that.) As it happened, we were running a system where the first person to answer one question became the last to answer the next. I’d answered first the previous question. With that many people on the panel, it was a long time coming back to me. I was a bit numb by the time it did.

My fellow panelists rambled through the standard answers. The “for public consumption” ones. Pleasant, inoffensive if occasionally stern platitudes with which everyone replies to questions like that, responses designed to gently shuffle the querant out the metaphoric door while maintaining the delusion of hope and allowing the respondents to feel as though they haven’t been total rat bastards. Above all, don’t offend the fans, since your livelihood depends on them. It’s not like the panelists were trying to con anyone, it’s just you stick around a business, any business, long enough, you pick up the pleasant lies they feed the customers and on some level it’s often easier to tap into those lies than to come up with something else. You believe them, at least for as long as you need to believe them. It’s a survival reflex.

All in all, I also prefer not to crap on other people’s dreams. But if a dream’s strong enough there’s no way to adequately crap on it. In college, I had a fiction writing course where we critiqued each other’s stories weekly, and the teacher repeatedly asked that we should be gentle and positive because the writer’s ego is a fragile thing and it would be terrible to drive someone away from writing with harsh criticism. I always thought that was a terribly wrong approach. Anyone who wants to write will do it regardless of what anyone else says. Sooner or later they may – may! – end up with something someone besides their mother or their best friend likes. (Bias puts blinders on us all.) Anyway, to get back to the panel, I’d just about gone comatose when whoever sat next to me said, “Steve probably has something to add” and shoved the mike in front of me.

I didn’t have anything to add.

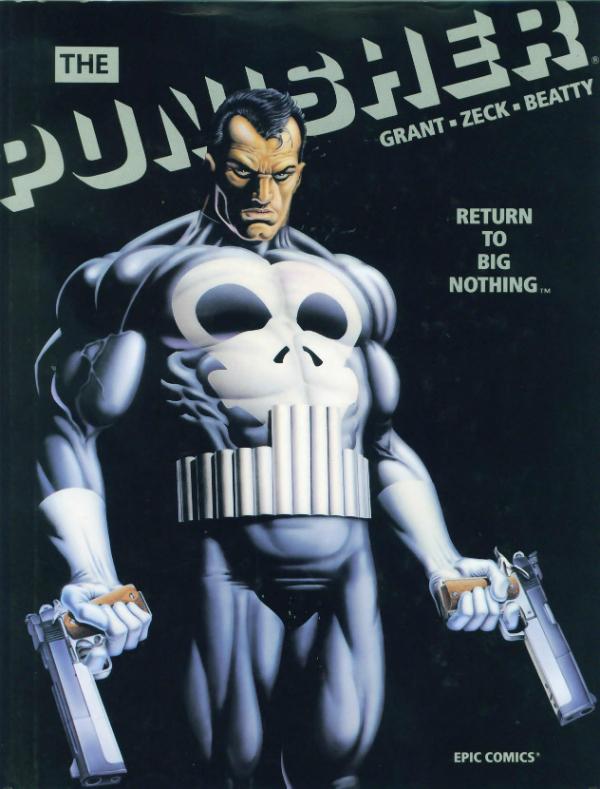

Punisher by Steven Grant and Mike Zeck

Then, just like that, I did. I was bored, I was tired of hearing the same old crap, figured sooner or later someone ought to lay the facts out, and was acutely aware I was the end of that particular road. I took a deep breath, and launched into the following tirade:

Why won’t an editor consider your work instead of the crap he accepts?

1) Your work may not be as good as you think it is.

2) It’s not actually an editor’s job to find new talent. It’s the editor’s job to get his books out. While most editors do try to look for new talent, that’s something that gets relegated to after all the required work is done, and the required work is never done.

3) Because editors have to get their books out, they usually prefer to work with talent they know can get the job done, professionally and on time. Professionally doesn’t necessarily mean great. It means publishable. New talent always represents a risk.

4) Every editor has parameters for the material his office produces. You may not understand those parameters. Just because you want to do something doesn’t mean what you want to do fits editorial needs.

5) Everyone’s taste is different, and any editor may actually like the books he’s producing, and he may think they’re good comics. Even if you don’t. He may think the talent producing them is top notch talent. Even if you don’t.

Finally:

6) Even bad work is harder than it looks.

Let me repeat that now: even bad work is harder than it looks.

I know. I’ve produced a lot of bad work. I hope I’ve produced some good work, I produced projects I think are good work, but – and far too many people in comics can’t get this simple concept through their heads – I’m not the one who gets to decide these things. Unfortunately, I also can’t afford to pay attention to anyone else’s assessment. There are projects I’ve written that I thought – in some cases, still think – were very, very good that were almost universally vilified, when anyone bothered to pay attention to them at all. I’ve done projects that got raves that I thought, still think, were just utter crap. Then again, I knew what I intended, and, generally, how short I fell. Readers/critics knew what they wanted. The problem is the two sets of criteria don’t necessarily, maybe even rarely, match up.

The fact is that what I consider the bad work was never easier than the good. In my experience, good work takes much less effort to produce than bad. It requires less forced focus, usually builds more organically. But that’s deceptive. If you go by those criteria, you can easily trick yourself into believing that effortless work is good work and that’s nothing like a universal principle either. From a creative standpoint, any rigid criterion for distinguishing good or bad is both handicap and crutch. Creating comics is less a question of good and bad than a question of success and failure. Failing to produce good work isn’t hackwork. Hedging your bets is. Counterproductively, hedged bets are frequently what readers and critics respond best to.

Distinguishing good comics from bad is something of a fool’s errand, partly because they remain mostly a commercial enterprise (it’s around this point in these discussions that art/alt comics fans write me off as “a superhero guy” and that’s supposed to invalidate my arguments, but, trust me, I’ve been around this insanity we call comics enough to know that a) if you ain’t self-publishing, you ain’t the person who ultimately decides whether your work is publishable, and whatever market your publisher is targeting is still intended to be a commercial market, and b) if you don’t know the ratio of sharp-to-crap is roughly the same in art/alt comics as in “genre” comics, you haven’t been paying attention) and commerce is always something of a distorting force on creativity, kind of the way gravity naturally distorts spacetime in Einsteinian physics, and partly because so very few people are able to differentiate what they like from what’s good. There’s an embarrassment factor there; nobody wants to believe they like crap. Let me put it bluntly: there’s nothing wrong with liking crap. Everybody does, hopefully not exclusively. What’s wrong is declaring crap to be good because you like it. That’s how you end up with the recent spectacle of Fletcher Hanks and his incoherent inanity being dug up from its grave after 65 years and marketed as surrealistic genius, or Jerry Siegel & Paul Reinman’s ugly, clumsy Mighty Comics misreproductions of Stan Lee & Jack Kirby’s pivotal Marvel work recategorized as “camp.”

Then again, I had a TV production professor in college who refused to allow anyone to discuss television in terms of good and bad. He had a term for it: buttermilk. He liked buttermilk. But some people like buttermilk and some people don’t. Does that make buttermilk good or bad? It’s not a question with an answer.

I grew up reading bad comics. What choice did I have? It was the ’60s. The early ’60s. Until underground comix got widespread later on (and, man, did I devour them when I found them) it was a rigged game. Someone recently asked me if I started out as a Marvel or DC fan. DC, no question. Marvel wasn’t even around then. But y’know what? If you were a 7 year old in the vanilla Midwest in the early ’60s, less a new decade than a drab runoff from the gray ’50s, DC Comics, specifically the superhero comics edited by Julie Schwartz, were it, man. There was nothing better anywhere that a kid my age back then could get their hands on that similarly promised, even at their most insipid, that things might possibly someday be more than the, as GK Chesterton put it, “cold mechanic happenings” the world back then seemed to be made of. A few years on, that wouldn’t be the case, but then The Flash, Green Lantern, The Atom, the Justice League, they were the closest you could come to the strange. They were pretty much the only door to genuine excitement available in the day, and walking through that door eventually got me here.

But good? I liked them, so, sure. I’d have said good. I’d have insisted. Look back now, what you’ll likely see is character-thin and plot heavy, straitjacketed into structures developed and preferred by Julie in the science fiction comics he edited. For all his reputation for infiltrating scientific fact into his comics, and he did, he cheated. A lot. Deathtrap escapes hinge on semantics, heroes miraculously develop exactly the (temporary) power needed to stop the threat du jour. In maybe the most egregious bit of stupidity in all Julie’s titles, world-hopping quasi-astronaut Adam Strange, collaborating with the Justice League, reasons that if kryptonite, a piece of Superman’s homeworld, will stop Superman, then a piece of a super-powered alien’s homeworld will lay the alien low. What the hell?

Mystery in Space #75 by Gardner Fox, Carmine Infantino and Murphy Anderson

It’s easily the worst Adam Strange story in the run. Fans of the day declared it the finest Adam Strange story ever. (If you reasoned out “Justice League!” the odds are with you.) Hell, the whole of comics history is punctuated with widely praised material that wasn’t very good. Comics fandom itself is built on twin delusions that ’40s comics represented a “golden age” and ’50s comics (aside from EC Comics) a Carthagenated wasteland only marginally redeemed by the late return of superhero comics. Neither is remotely accurate. While hardly devoid of good comics, the “golden age,” once the cherrypicking stopped and much material became available, turned out to be a vast dumping ground of utter swill, while ’50s comics are a gold field for those willing to go panning for it.

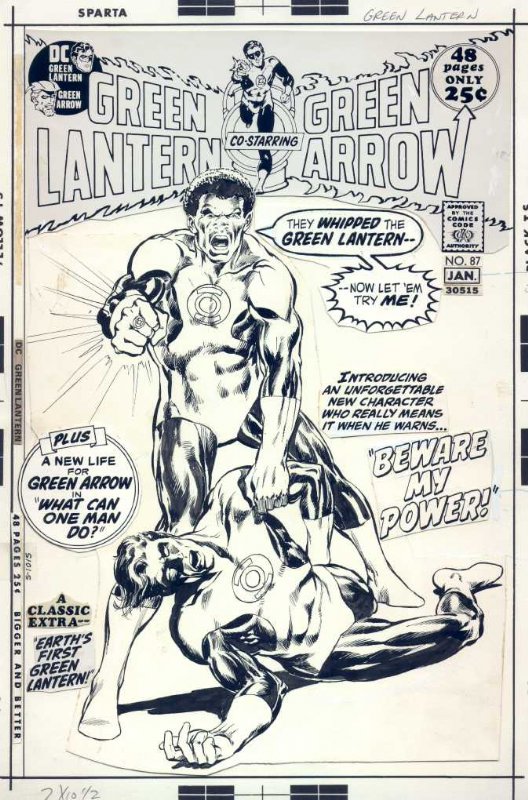

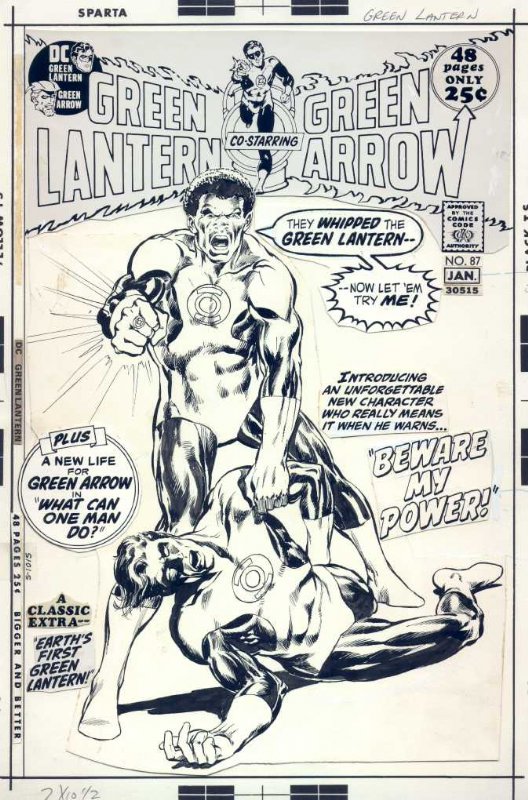

Green Lantern/Green Arrow #87 by Denny O’Neil and Neal Adams

As mainstream comics go, the most influential of the late ’60s may be Denny O’Neil & Neal Adams’ Green Lantern-Green Arrow, which briefly staved off cancellation in a decaying market by launching a short-lived move toward “relevant comics.” This was pretty quickly crushed by the urge to “make comics fun again” (i.e. avoid controversy) but it came back with a vengeance in the ’80s as GL-GA fans broke into the business and launched their own variants. Not too long ago, out of morbid curiosity, I asked various contemporaries in comics if there were any comics they loved when younger that they find embarrassing to read now. Almost without fail: Green Lantern-Green Arrow. Yet it was still a huge breakthrough in its day and its influence continues to ripple through the medium.

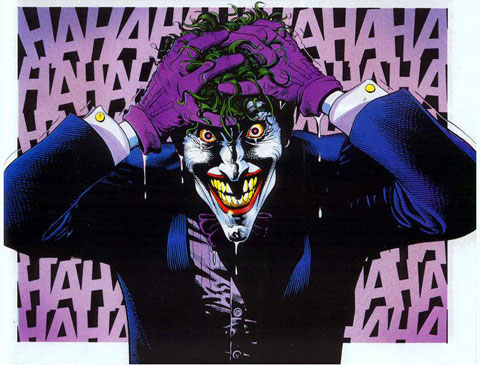

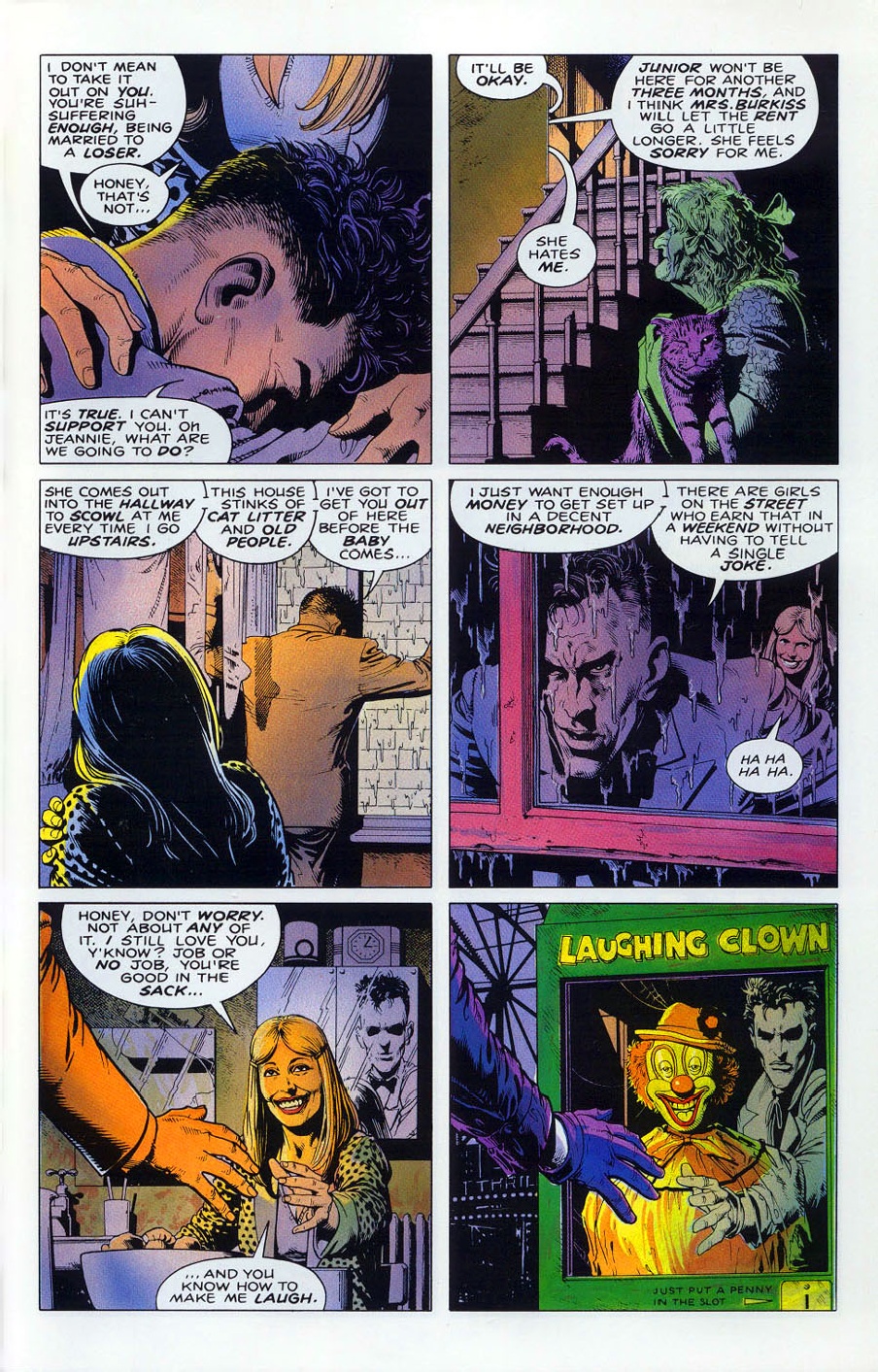

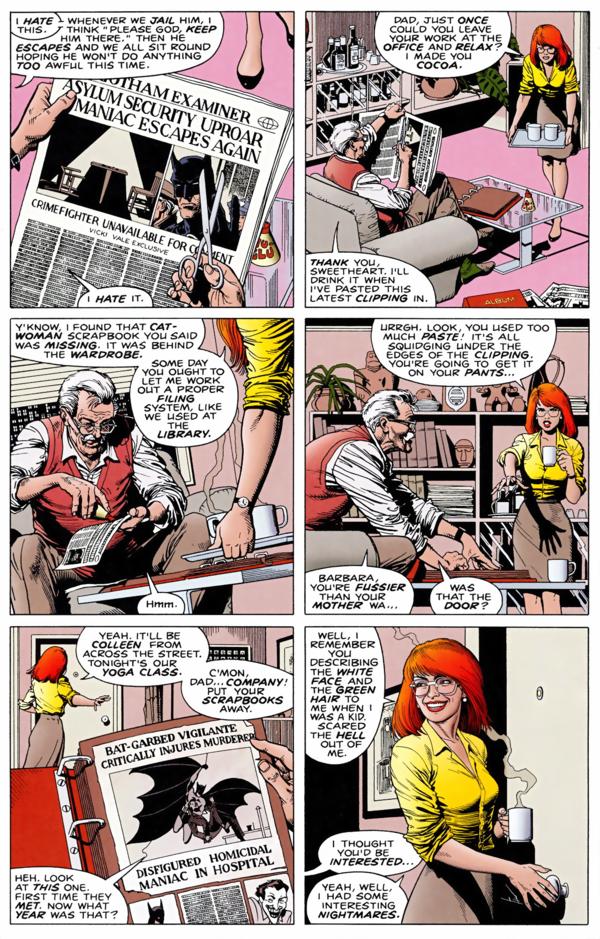

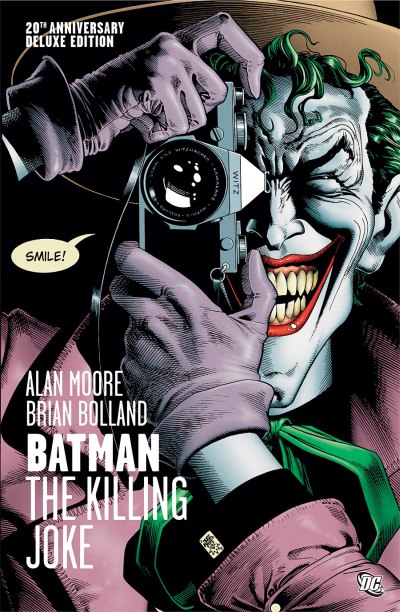

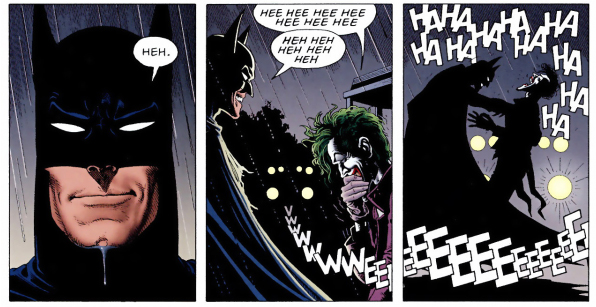

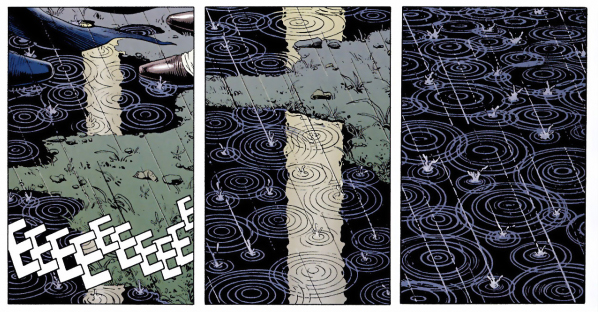

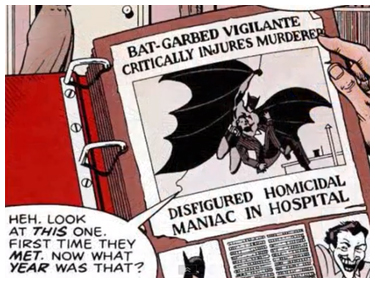

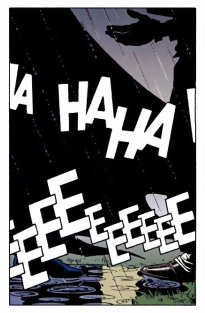

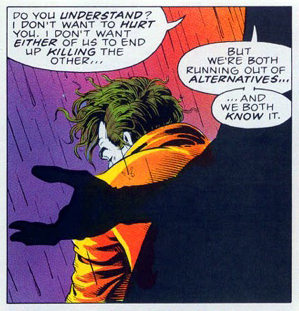

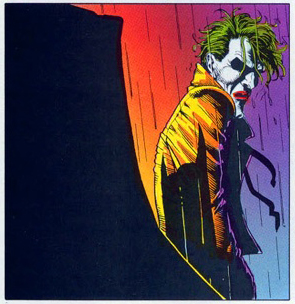

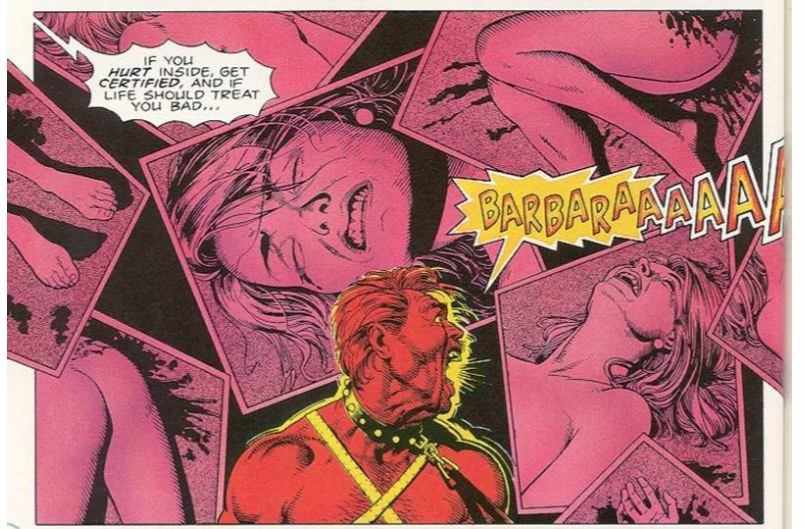

Killing Joke by Alan Moore and Brian Bolland

The list of highly touted bad comics go on and on. Few stories, even Batman stories, are as bad as Alan Moore’s The Killing Joke, an empty exercise in cruelty that depends on sleight-of-hand, Alan’s always splendid use of language and Brian Bolland’s phenomenal art to keep audiences from seeing the joke not only doesn’t have a punchline, it doesn’t even have a joke. That didn’t stop it from becoming, with The Dark Knight Returns, one of the two lynchpins of virtually all subsequent Batman interpretations. Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman is among the most lionized series in comics history, but its champions conveniently overlook the almost literal deus ex machina endings diminishing many early arcs, with hero Morpheus appearing from left field at the climax to terminate all storylines with languid boredom and a wave of his hand. That’s not a quality you traditionally find in good endings, in any medium. (Ever see that SCTV fake ’40s crime film that features a crusading DA trying to take down a mob boss that ends with a courtroom-standoff-at-gunpoint abruptly broken up by news “the Japs” have attacked Pearl Harbor, whereon all players throw down their weapons and rush out together arm in arm to sign up for military duty as Patriotic Americans? Same principle.) On the alt side, I’ve always wondered if fans of Craig Thompson’s breakthrough graphic novel Good-Bye Chunky Rice, which helped trigger mainstream publisher interest in alt comics, were unaware it was sentimentalized treacle, were willing to ignore it, or if that’s where its main appeal lay.

I cite these as bad comics not only because they all changed the course of comics in some way, but also because they were each, in their way, quite good. (With Sandman, it fully merited its reputation the moment Neil dropped that annoying gimmick.) If this seems a contradiction, welcome to comics. I’m not suggesting they shouldn’t be read, or enjoyed. I’m not even suggesting badness is an especially good reason to not read a comic book. There are worse things for a comic book to be than bad. A problem with discussing bad comics is that while there are a few really bad enough to be memorable, there are very few really bad enough to be memorable. Many are good enough to be momentarily enjoyable, like eating a Twinkie. Some, like those mentioned in the previous paragraph, are good enough to have altered the business.

Most bad comics are simply forgettable, and it’s more trouble to try to remember then than they’re worth.

As we grow up reading comics, we end up expecting maybe a little too much from them, or end up expecting things the medium maybe just isn’t built for. It’s a medium of shorthand, of tricky balance. As much as many have wanted comics to take their place among the literature of our time – some have even tried making “comics literature” an accepted term – it’s not really a literary medium. It’s not movies either. It’s that words and pictures thing that confuses everyone. It’s a pop medium, a commercial medium, a strangely hermetic medium, where, sure, we may adore Will Eisner and Harvey Kurtzman and Jack Kirby and whoever else someone has put forth at one point or another as developing the “rules” of comics, but, really, it’s a medium without rules, where no theory ultimately holds sway. It has boundaries – no sound, no real movement, space limitations – but no orthodoxies, no matter how many publishers, editors, critics, readers, artists and writers have tried inflicting them. No matter what theory, what orthodoxy anyone produces about what comics should or shouldn’t be, someone else produces a comic that shatters it. A lot has changed in comics since I began reading them, but, as they were long before I began reading them and despite all the many, many efforts to gain respect for comics and have them declared “legitimate,” we remain an outlaw medium. Virtually anything goes here. This is the wild west.

In that context, terms like good and bad have considerably less resonance, given there’s no authority of any merit and “badness” has never been much of an impediment to sales, popularity or, frequently, enjoyability of a comic. What does it really matter if a comic is ultimately good or bad, by which we really mean, let’s face it, appealing or disappointing? Allow me to suggest we replace thinking in terms of good or bad altogether with a different and arguably more useful (if equally subjective) yardstick:

Is the comic/graphic novel in question interesting?

That’s what we all really want from comics, right? That what I wanted when I was 7, certainly, it’s what many comics I read delivered whether I ended up deciding I liked them or not, and it’s what I look for today, along with (I suspect) everyone else who still reads comics.

Anything else, however welcome, is gravy.

__________

Click here for the Anniversary Index of Hate.