This is part of a roundtable on the work of Octavia Butler. The index to the roundtable is here.

__________

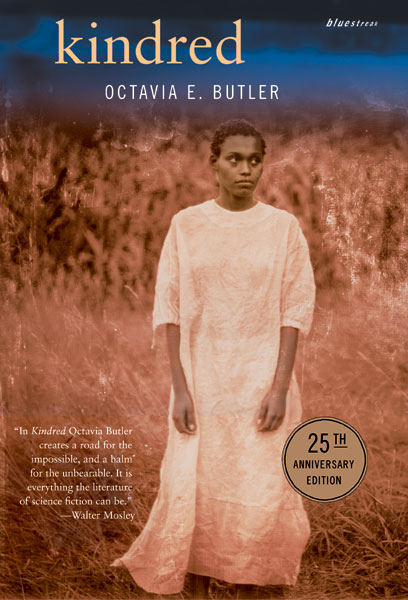

When I got into college, Pasadena City College,…I heard some remarks from a young man who was the same age I was but who had apparently never made the connection with what his parents did to keep him alive. He was still blaming them for their humility and their acceptance of disgusting behavior on the part of employers and other people. He said, “I’d like to kill all these old people who have been holding us back for so long. But I can’t because I’d have to start with my own parents.” When he said us he meant black people, and when he said old people he meant older black people. That was actually the germ of the idea for Kindred (1979)

I’ve carried that comment with me for thirty years. He felt so strongly ashamed of what the older generation had to do, without really putting it into the context of being necessary for not only their lives but his as well. I wanted to take a character, when I did Kindred, back in time to some of the things that our ancestors had to go through, and see if that character survived so very well with the knowledge of the present in her head. – Octavia Butler

First, a spoiler-free refresher on Kindred if you haven’t read it, or if you can’t remember it: On July 9, 1976 (which was contemporary when it was written), Dana feels dizzy, and then collapses, while unpacking in her new house. She comes to on the banks of a river she has never seen before. Luckily, space and time travel have a short jet-lag period in this world, because almost immediately after she arrives 161 years in the past, she saves the life of a little red-haired boy drowning in the river beside her. We later learn that the boy is Rufus, her great-grandfather. Rufus will grow up to have several children by one of his future slaves, Dana’s great-grandmother Alice. But for now, he is a boy who needs saving, and so she saves him. Dana continues to save him over the course of the story, because consanguinity has bestowed upon Rufus the ability to call Dana into his time when his life is in danger.

Now, a spoiler free plot point: Dana loses her left arm on her way back from the last of these travels. It has to be amputated in the present-day, as a result of an injury she sustains while coming back. She also sustains a permanent scar on her face from being kicked by a slave-owner after falling down.

Amputation and scarring are permanent, and should not be the metaphor to represent the injuries that slavery has caused to those racialised-as-Black in this day. This isn’t to say that there are people racialised-as-Black living outside of structural racism, or that if you ignore reality, injustice goes away. Rather, what I want to hold up for scrutiny is the notion that injury and impairment are necessarily and perhaps even inevitably, a part of identity for descendants of slaves and those who look like them in contemporary America.

If you’ve read Wendy Brown, you’re probably familiar with what I’m getting at. If not she’s a political science professor at University of California, Berkeley, and my question is related to the one Brown poses in States of Injury. That is, “how does a sense of woundedness become the basis for a sense of identity?”, but my response is different. Brown argues that its the capitalistic superstructure that we need to jettison in order to bring about liberation. You see, by getting mad that the path to your piece of the pie is unjust, you maintain that the pie really is the thing you value. “The reviled subject becomes the object of desire,”she warns.

The horrors of the slave trade seem to lend its support for her proposition. What were the slaves doing? They were making things for people to buy while keeping the cost of production minimal. They were working on sugar plantations so the land owners could have cookies, and cakes, and boiled sweets. They were working on cotton plantations so the land owners could look fashionable. They were building Georgian colonial homes to shelter the plantation owners from the brutal southern heat and the back-breaking work of beating people within inches of their lives. Though slavery is not capitalism proper, it has the capitalist’s existential project at its core: that the making and buying of things for profit, determined by membership in stratified social classes, should be the primary preoccupation of state and society. All the while, the slaves wanted what the slave owners had- the spoils of the American Dream, despite the fact that it was the Dream that justified their enslavement. We still do this in various forms today.Many groups and movements criticise the state as a monolithic site of oppression qua unjust dominance, but then seek its protection under the logic that state dominance is only unjust if its dominating the wrong demographic.

I’m not convinced that capitalism is the problem though, or that anarchy or communism are potential solutions. Perhaps domination is inextricable from capitalism, but domination doesn’t belong to any particular political economy any more than religion has monopoly on morality. Yes, her experience of enslavement permanently impairs Dana. But let’s not elide over the fact that her impairment would not be a disability if her society did not make safety and self-actualisation a two-handed commodity.

So that’s why I loved Kindred, but am also a little wary of it. I loved that it shows so vividly the kinds of things that happen when you put ego and profit above universal human dignity and justice. But it also seems to suggest that injustice is primarily a problem of unjust commodity distribution, rather than a problem of us valuing a questionable set of social goods. It also reifies various forms of injustice by suggesting that we need to expand the class of people who can afford freedom, rather than question why freedom is so closely tied to desert and not something else. Do we really want to say that freedom is a cookie given only to those who have worked hard enough at the right things? Perhaps so, but then we’d need an account that can explain why freedom’s metaphysics only kick in after you’ve joined the right social club. If you’re really free, you need to be free from the start, not after conquering (or being born having conquered) a set of social ordeals.

“I never realized how easily people could be trained to accept slavery,”Dana thinks to herself, after a few travels back into the past. I now think to myself, “You can make a person accept nearly anything, if you tie acceptance to their livelihood”. The characters in Kindred that question slavery either attempt to run away, or hope to one day get their free papers. I sympathize with the characters who tried to run away, but I’m sympathetic of the stance of waiting and hoping. It’s just that, waiting for your free papers suggests that you really are property (as many slaves had been convinced), and continues to hold the plantation owner as the ultimate arbiter of freedom. If we untie our livelihood from needing to dominate others, we can start to live differently, and oppression becomes a social condition, rather than a permanent personal injury.

No, oppression is not an amputation, but a sign that you want to use that two-handed tool too. Whether or not that’s a bad thing is perhaps another conversation. What’s important though, is that we distinguish between “I want to be free”and “I want what those who deem themselves free have”. Pursuing the latter has the unfortunate and pernicious effect of stopping the conversation about whether self-professed free people are really any freer than those they dominate. There’s no need clamouring over one another for pie when what you really want is chocolate cake anyway. The metaphor might be trite, but you’d miss it if you took the injustice-as-amputation metaphor at face value.