This is something of a follow up to my review of Dan Clowes show at the MCA which ran in the Chicago Reader last week.

_______________________

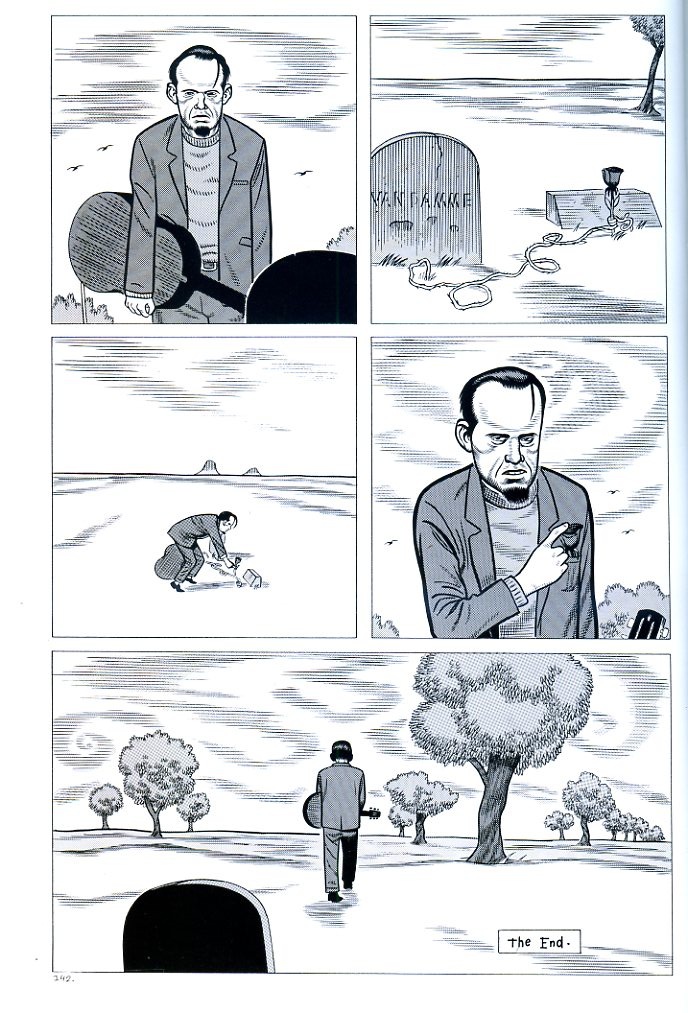

Dan Clowes published Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron as a collection in 1993; he published Wilson in 2010. The first is a surreal, dream-like pulp grotesque; the second is an exercise in the quotidian mundanity of literary fiction. Yet, despite their separation in time and genre, the two books have a major plot strand in common. That plot strand consists of two parts. (1) A man searches for his wife who has sunk into sexual debasement. (2) She dies.

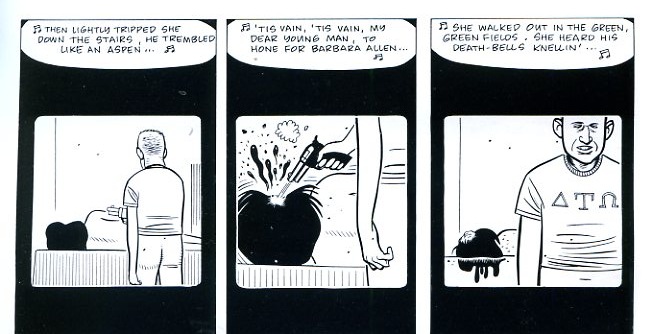

In both comics, also, the women’s stories are simultaneously the center of the narrative and marginal to the psychodrama of the husbands. In Velvet Glove, Barbara Allen’s death happens in a blink-and-you’ll miss it off there on the panel edge joke, and is “retold” through a filmed showing for Clay Loudermilk’s benefit.

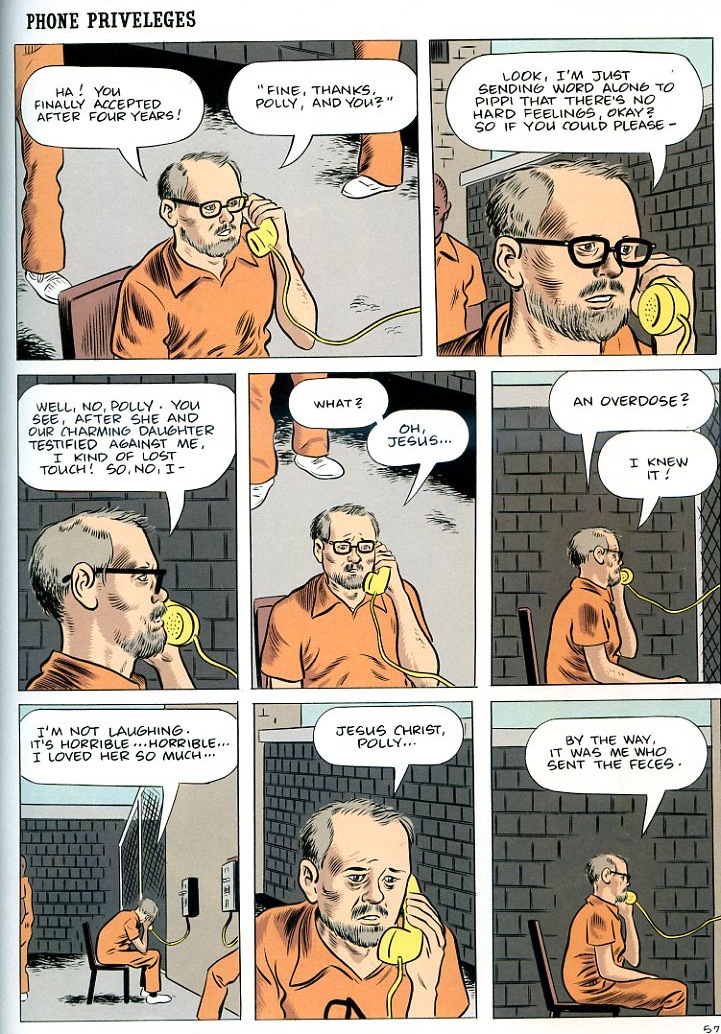

In Wilson, Pippi’s death occurs completely off-panel, narrated to Wilson over the phone as he sits in prison. Both deaths are carefully, deliberately degrading. Barbara is shot in the head during a pornographic fetish film; Pippi dies of a drug overdose. The anti-climactic awfulness of their passings is both a joke and a validation, underlining the nonsensical, adult viciousness of Velvet Glove and the banal, adult viciousness of Wilson. As in a gangsta rap song, or in one of the country death songs that both the names “Barbara Allen” and “Loudermilk” reference, coolness and a kind of manliness or maturity is conveyed through the killing of women, and, through the studied casualness of that killing.

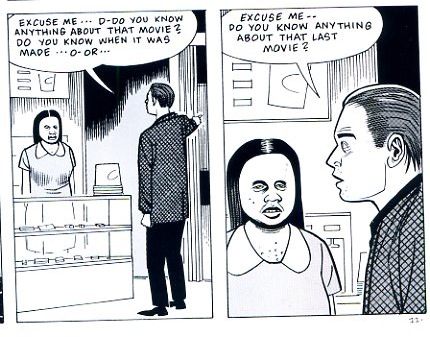

That maturity is in fact what is at issue is made quite clear in both books, albeit in different ways. In Velvet Glove, the search for Barbara Allen is tied repeatedly to the obsessive search for pop culture collectibles…and thereby to the comics medium. Clay Loudermilk discovers Barbara in the opening pages of the comic performing in a violent, bizarre cult fetish film — a provocative, unique bit of alternaculture which stands in for and references Like a Velvet Glove itself. Loudermilk’s shocked need-to-know following the exhibit is diegetically because his wife was in the film, but for alternative comics fans it also has to reference the awakened passion of the collector.

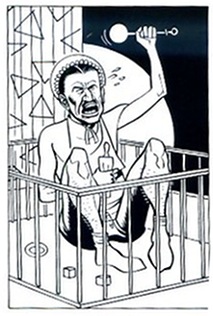

This is only underlined when the search for Barbara becomes obscurely enmeshed with an iconic cartoon character, Mr. Jones, who appeared in old-time advertisements and is improbably tattooed on Clay’s foot — as if his search for obscurities has become a mark of personal identification, so that he has become his own infantile obsessions. When he shakes Mr. Jones, it is not to transcend him, but to embody him. His arms and legs (and Mr. Jones tattoo) are torn off by a steroidal, adolescent-power-fantasy of an antagonist, and Clay becomes a swaddled stump, cared for and fussed over like a baby.

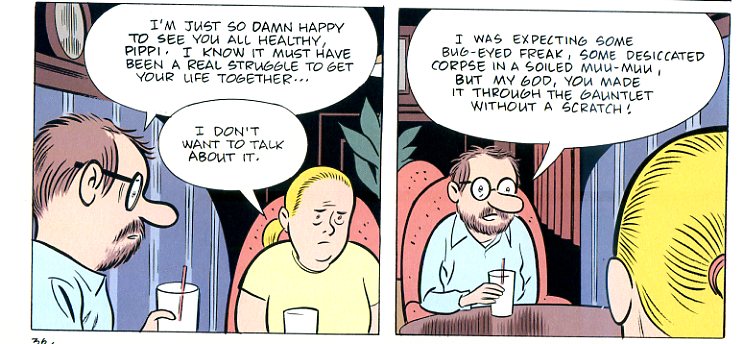

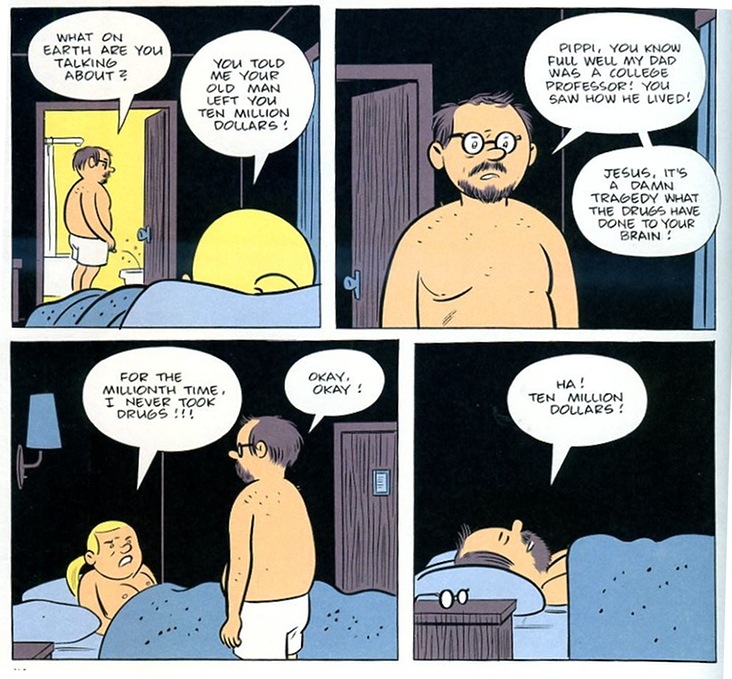

In Wilson, the connection between women, comics, and childhood is routed (as is just about everything in Wilson) through Charles Schulz’ Peanuts. The non-funny gag strips substitute glib profanity and gallow’s humor for Schulz’s bizarre aphasiac non-sequitors and odd tangents, but the model is still clear enough. Pippi, then, is a grown up little red-haired girl; Wilson a grown-up Charlie Brown who, of course, hasn’t really grown up. The shifting styles veer back and forth between cartoonish/neotenous and more realistic, so that Wilson exists in a constantly vacillating iconic no-man’s land between kids’ fodder and serious fiction.

In both works, then, comics, cartooning, childishness, and women function as a knot of meaning, loathing, and desire. Clowes is a very self-aware cartoonist; I don’t think it’s an accident that the initial fetish film Loudermilk sees includes an image of a grown man dressed as a baby and crying.

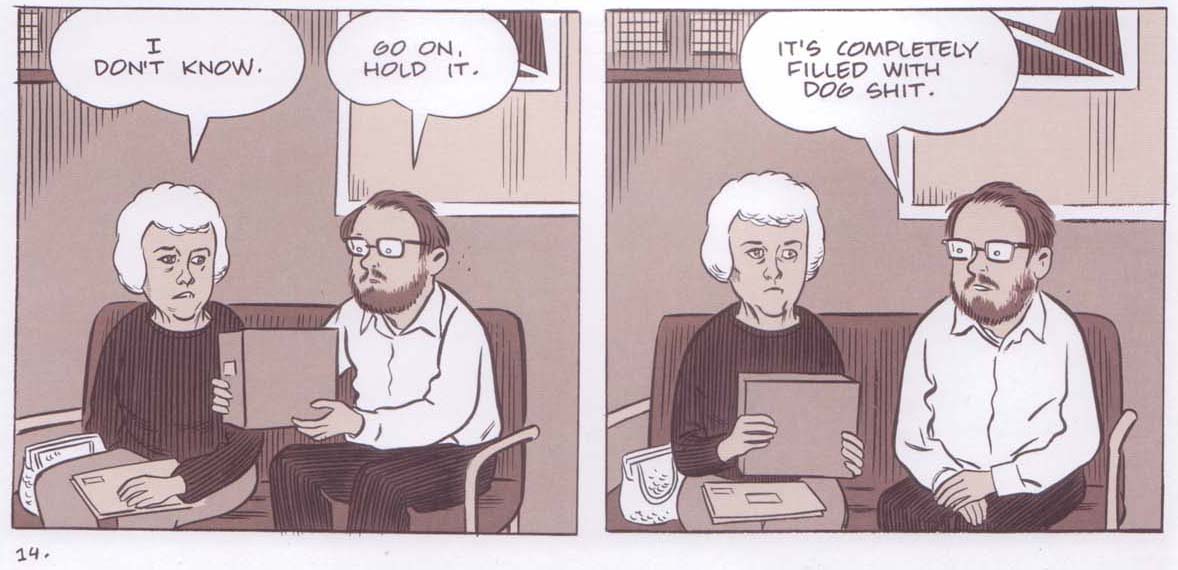

Similarly, I’m sure the Freudian connotations of arrested development and desperate, childish bid for control are entirely intentional when Wilson sends his in-laws a giant box of dog shit. Both books present their protagonists as infantile, or in danger of, or tempted by, infantilization. Both books in turn, link their own medium of comics to that same infantilization. The narratives then become engines for demonstrating and reveling their own childishness, while simultaneously disavowing it.

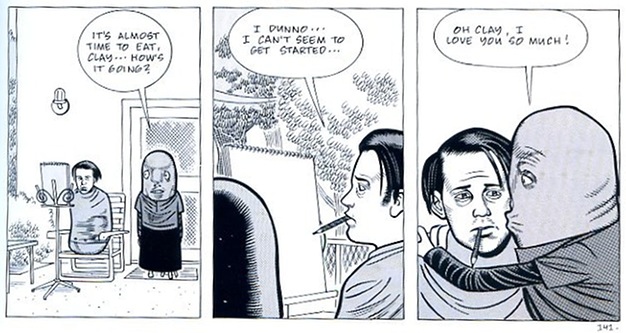

Both the reveling and the disavowal are accomplished in no small part by making comics women, and then killing them. As Clowes is I’m sure well-aware, a fetish is technically a displaced symbol of the mother. Barbara as collectible, then, functions as a doubly referring, vacillating system, feminizing comics and comicizing femininity. Again, the final image of Clay, armless and legless, trying to draw on a pad with a pencil in his teeth while his monstrous fish girlfriend declares her love, fits neatly here.

It’s a masochistic, self-pitying vision of comics artist as child — distanced both through its own adult violence and through its vision of the femininity as monstrous. Similarly, Barbara’s brutal death is commanded by a young girl who spins out the stories that are used in the fetish film. The comic, then, is, Clowes tells us, under the control of a feminine infant — whose whims result in very adult violence and femicide. The narrative’s grown-upness is guaranteed by the fact that it makes sexualized violence out of a child’s story.

In Wilson, Clowes actually self-reflexively acknowledges the comics own investment in female degradation. Wilson insists that Pippi, after leaving him, ended up on the streets, in a life of prostitution and drug use. She keeps telling him that much of this is not true, but he either doesn’t believe her, or doesn’t want to listen to her.

In the terms of the narrative, Wilson wants Pippi to have fallen apart after she left him because he wants her to have made the wrong decision. But the comic itself seems to have its own motivations. Yet, despite all her denials, Pippi does in fact die of a drug overdose. Clowes, like Wilson, it seems, just can’t quite resist the idea of Pippi, or Barbara, humiliated and dead. And no wonder; violence, sex, perversion, death — everything that separates Clowes from Charles Schulz, or from the infantilized medium of comics, is neatly summarized in the image of a woman’s corpse. If, Bloomian poets must kill their fathers to replace them, Clowes suggests that serious comics creators must kill their mothers to escape them. Genius comes out of her grave.