After calling Scarlett Johansson “the smartest, toughest female action star,” film review Justin Craig declared: “it’s time ScarJo gets her very own Marvel franchise.” But when asked if a Black Widow film is in the works, Johansson had to fumble her way through a politic non-answer: “You know, I think it’s something that, um, again I think Marvel is is certainly, um, listening, and if, you know, working with them for several years now, you kind of see how, ah, they respond to the audience, um, demand I think for something like that.”

Marvel president Kevin Feige says it’s “possible,” but makes no promises. Meanwhile, Johansson is creating her own superwoman franchise. She literalizes her Black Widow codename by playing an actual man-eating spider in Under Her Skin, and her voiceover computer operating system Samantha in Her is way way beyond anything Tony Stark could build.

But I had my highest hopes on Luc Besson’s Lucy.

If there’s a director geared for writing and shooting a superheroine movie, it’s Besson. His 1990 Le Femme Nakita spawned an immediate Hollywood remake (though there is no reason to see Bridget Fonda in Point of No Return) and later a Canadian-made TV series (thank you, USA Network, for keeping the French name). The Fifth Element was a bit of a mess, but an entertaining one, especially the fact that the “supreme being” is supermodel Milla Jovovich cloned from a severed hand to protect Earth from a giant black cloud of evil space death. I think magic space stones were involved too—the same plot Marvel seems to be headed toward now. And let’s not forget The Professional, Besson’s hyper-violent pedophiliac action-thriller co-starring twelve-year-old Natalie Portman (no wonder she fell for Chris Hemsworth when he and his hammer dropped out of the sky in 2011).

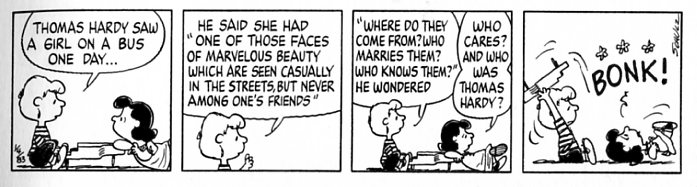

I’m not really sure what Besson has been doing since the 90s, but it did not further hone his film-making skills. Lucy is not a good movie. But it is a superheroine movie. Lucy, like so many of her comic book counterparts, is the next leap in human evolution, one accidentally triggered by a ruthless drug cartel that continues to supply the script with shootouts and car chases. Lucy has Professor X’s mind-reading and telekinetic skills, invulnerability to pain, a cybernetic ability to interface with machines and airwaves, and the power to change her hairdo at will. Johansson doesn’t wear an “L” on her chest (the t-shirt is cut too low), but her name does meet Peter Coogan’s requirement of “a superhero identity embodied in a codename” since Lucy, as we’re told very early, is the name of the first human being (who also makes two pleasantly bizarre cameos).

Morgan Freeman, reprising his science-guy helper role from the Batman trilogy, delivers some painfully scripted superpowers-science in the form of a literal lecture, complete with Powerpoint bullets and audience Q&A. Besson intercuts these with Johansson’s literal bullets and scantily costumed T&A. The film begins in Taiwan and ends in Paris, with occasional French and Korean subtitles. It would be significantly improved if the subtitles were deleted and the English dialogue dubbed in Latin or Old Norse or any other language the majority of viewers won’t understand. Because then we could enjoy the sequence of spectacle, which is Besson’s well-disguised strength.

Freeman’s faux-science voiceover distracts from the fun by pretending that the film suffers from internal logic. It doesn’t. Although the plot ostensibly follows Lucy’s brain growth, intercutting incremental percentiles from 10% to the climatic 100%, her actual superpowered behavior is random. When a kick to the stomach bursts the bag of drug-mule super-serum in her intestines, Besson flings Johansson around his rotating prison set till she’s writhing on the ceiling. This doesn’t really make sense—is she flying?—but it looks cool. The CGI team tries to disintegrate her during her flight to Paris, which looks cool too, but what exactly does that have to do with Freeman’s immortality soundclip? Once recovered, Lucy can dispose of a dozen armed cops with a flick of her hand—although for some reason those pesky martial arts gangsters require time-consuming one-by-one levitation. Also why, as she’s teetering on omnipotence, is Paris traffic quite so challenging? Oh, and why do her very first acts of drug-induced super-intelligence include hand-to-hand combat and two-gun marksmanship? Are those skills about brain capacity?

I prefer Johansson’s performance before her robotic transformation. Imagine the Black Widow quivering in fear and vomiting on herself at the sight of a blood. Johansson fans could argue that Lucy should only be analyzed in relation to Her, since Lucy builds a supercomputer and downloads herself in her final moment of corporeal existence, ending the film with a text to her cop boyfriend: “I AM EVERYWHERE.”

But I’m gong to reroute us to 1933 instead.

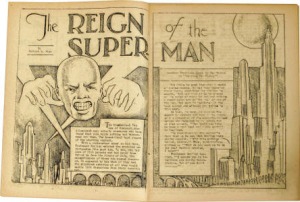

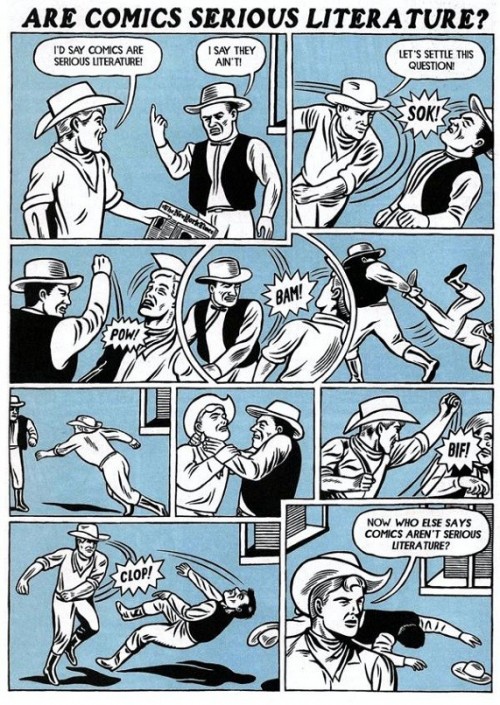

If you don’t think Lucy counts as a superhero movie, read Jerry Siegel’s short story “The Reign of the Superman.” Before teaming up with Joe Shuster to create their comic book Superman, Siegel wrote a tale about a ruthless scientist who uses a starving vagrant as his lab rat. Lucy is a privileged college student, but she’s equally clueless when abducted and implanted with a mysterious super-drug. Siegel’s is derived from an asteroid, but its effects are similar. Soon his anti-hero is reading-minds and projecting his thoughts across the universe too.

Unfortunately such unlimited power transforms him into a hate-mongering monster bent on world domination. Lucy’s transformation leaves her morally challenged too. She murders a hospital patient to make room for herself on a surgical bed with the excuse that the guy wouldn’t have lived anyway. When her cop sidekick comments on the tourists barely scrambling out of the way of her car and the string of exploding wrecks she’s leaving in her wake, Lucy says something about the illusion of death, which apparently gives her a license to kill and collaterally damage.

But, like Siegel’s second and far more famous Superman, Lucy finds a way to hold on to her humanity. When her hunky sidekick complains he’s no help to her, she kisses him. She needs him because he’s a “reminder,” she says. One of the students in my Superhero course made exactly that argument about Lois Lane.

So while Lucy is not the leap forward in superheroine evolution I’d hoped for, perhaps Johansson, like Siegel in “The Reign of the Superman,” is running some experimental test work before delivering a full dose of her superwoman prowess.