I realized about halfway through a recent interview with Cult Youth founding member Chairman Ca that I was asking the wrong questions. I was nearing the end of my stay in Beijing when I finally got a meeting with Ca, who was seeming more and more like the leader of the only real contemporary comics’ collective in China. In him I sought proof that Chinese comics (or “Manhua”) not only had a present, but a future; a future that would create a discursive political/social space for young critics like it had for so many countries before China. In him I found not the leader of a comics’ revolution, but a very talented dude who likes to make comics about Zombies.

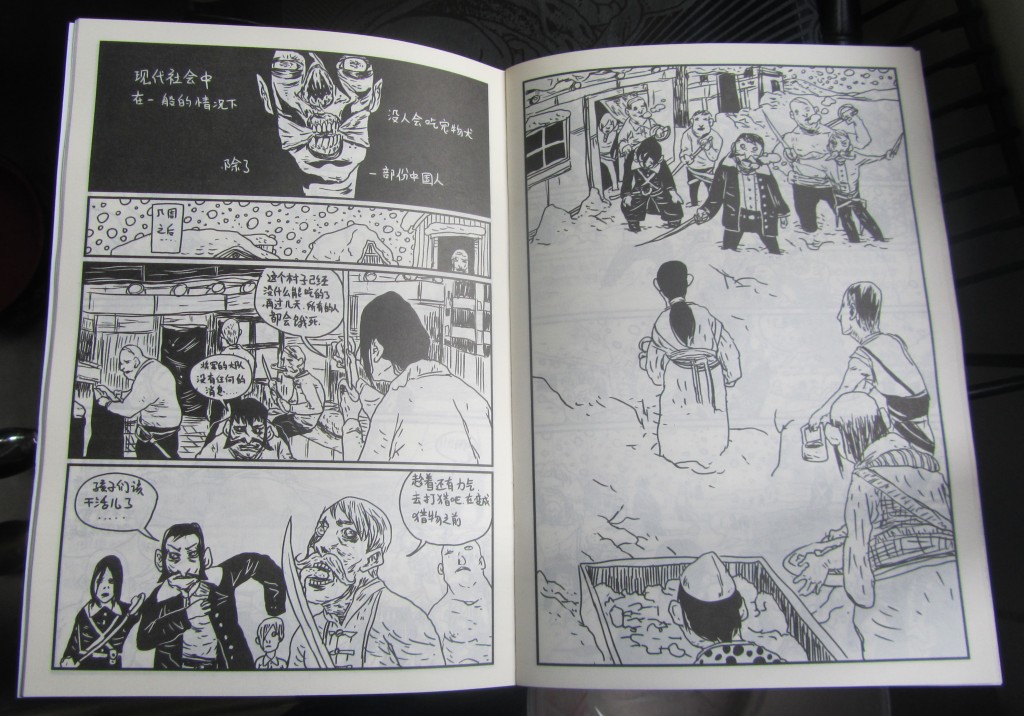

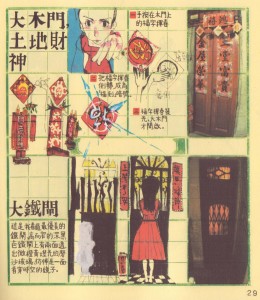

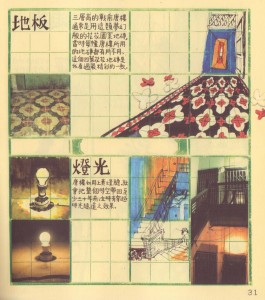

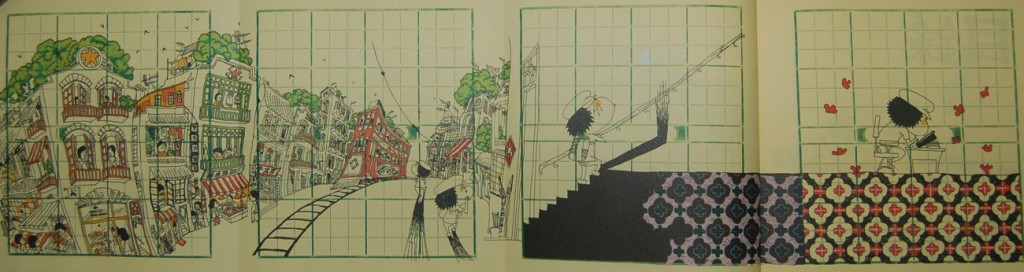

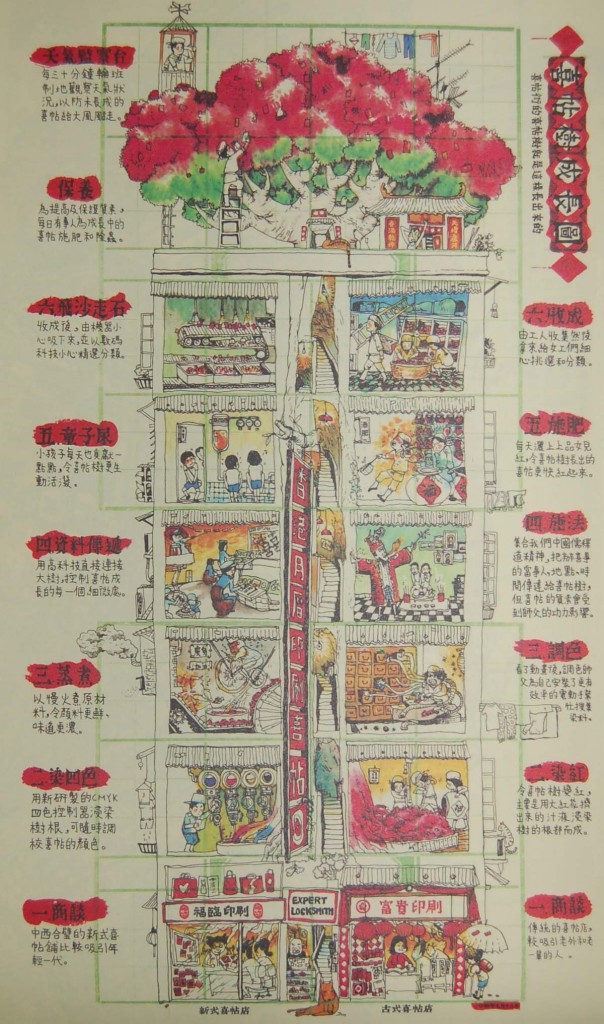

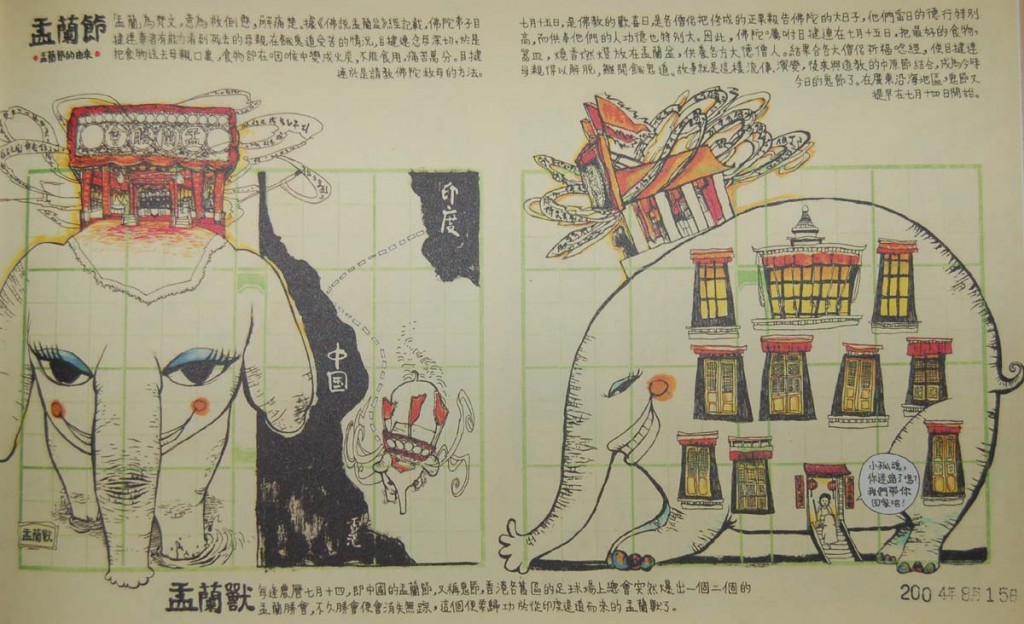

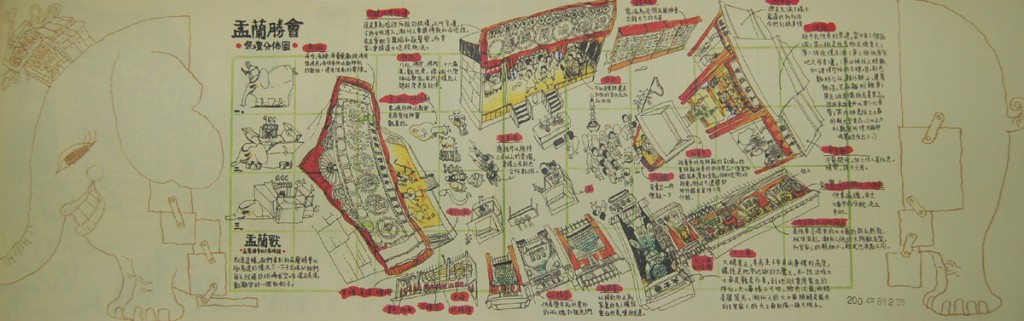

Pages from Chairman Ca’s Zombie Pie

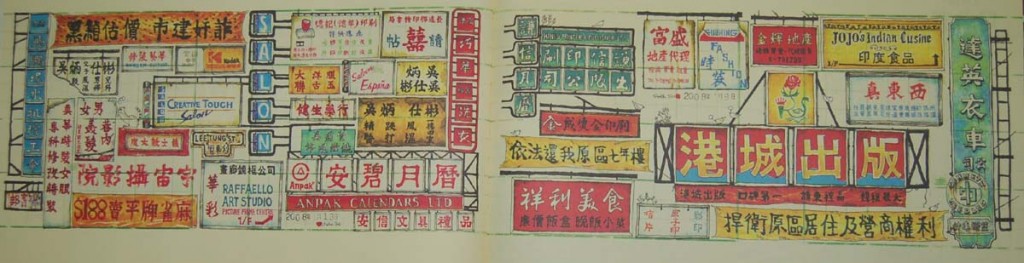

But before we discuss the salience of Cult Youth (CY), it is important to understand the larger comics’ community (or lack thereof) in which they operate. To put it simply, besides CY and a few rare exceptions, there aren’t any contemporary Chinese artists producing comics. However, this doesn’t mean that Chinese people aren’t avidly consuming comics on their iPhones and knock off iPhones alike. You see, the comics that are popular in China aren’t made in China, they’re translated Japanese imports. If you are remotely familiar with the history of China-Japan relations — from The Rape of Nanking all the way to the Diaoyu Islands — hearing that China openly embraces Japanese culture might appear contradictory to popular opinion. And for scholars of Manhua’s history (which you are about to get a primer on!), the reality would seem even stranger. As I’ll explore today, it somehow works that the culture which has youths actively devoting weekends to reading translated Japanese comics is the same culture where you can still read bumper stickers like this:

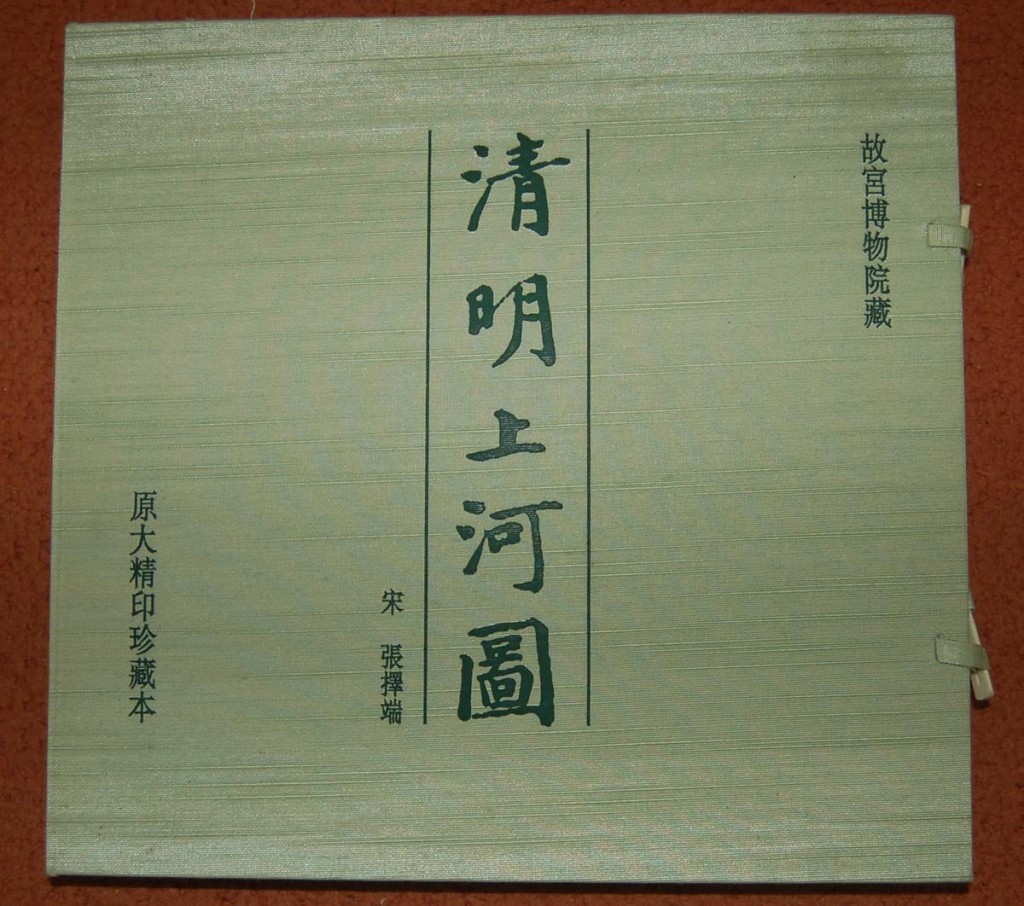

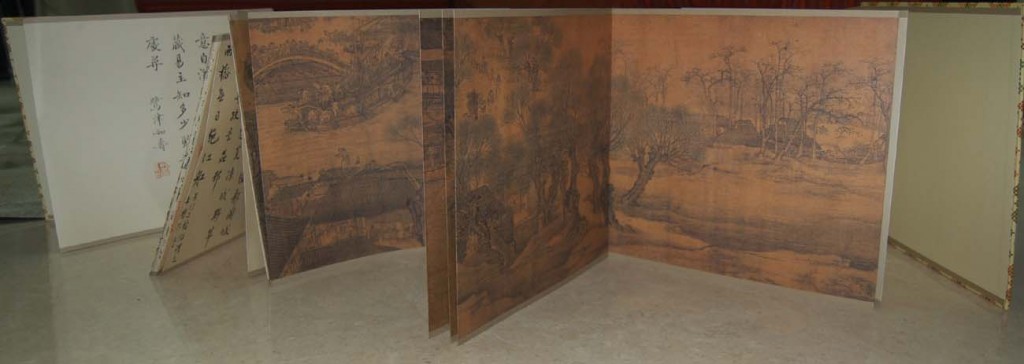

The history of Manga and Manhua have long been intertwined. The shared heritage should be evident from the name “Manhua” itself, a term adopted by Chinese to approximate the name “Manga” that Japanese caricaturist Hokusai Katsushika famously gave to his depictions of everyday life back in 1814. For a long while after that, Japanese held regional dominance over what was produced under that term, including work like Li De’s strangely Western-like The Rat’s Plaint in 1891. But as Japan-China relations soured under the weight of Japan’s imperial tendencies in the early 1900s, Manhua and Manga saw a clean break.

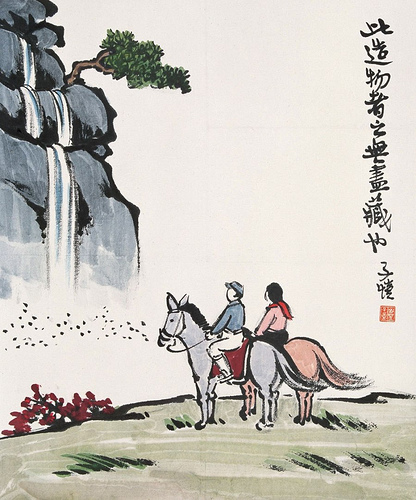

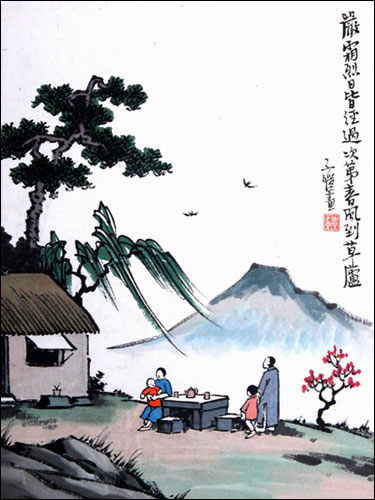

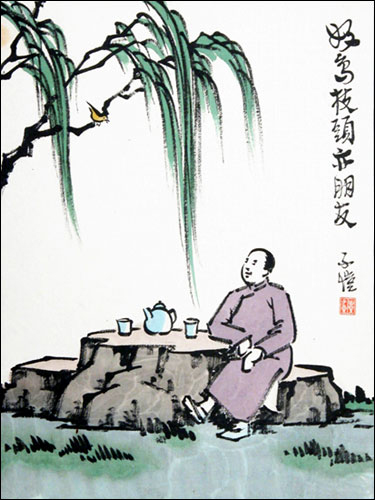

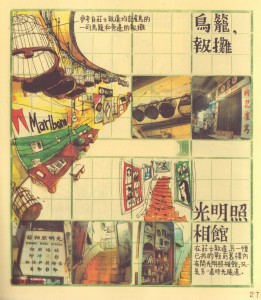

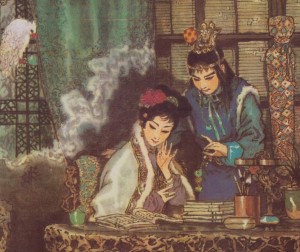

That clean break is perhaps best exemplified in the clear lines of Feng Zikai, who emerged in the early twentieth century as China’s preeminent comics artist. According to the wonderful Hong Kong Comics: A History of Manhua by Wendy Siuyi Wong, it was Zikai’s first published collection of cartoons, Zikai Manhua, in 1925 that better defined “Manhua” as a distinct art form in Chinese society. Through the work of Zikai, Manhua transformed from a loose pan-Asian signifier to describing a specialized Chinese art form with a common aesthetic. I’ll pause here to share some of Zikai’s art, which understandably galvanized a whole nation to define a term around it:

These Feng Zikai’s illustrations come via Cultural China and China Online Museum (where I encourage you to take in many more pieces)

Before long, Manhua became a venue for the political as the nation grew increasingly resentful of Japan’s growing regional dominance. In 1927, the Shanghai Cartoon Association — the first cartoon society of its kind in China — formed as a gathering point for a growing roster of Manhua artist. Founding members included Ding Song, Zhang Guangyu, Lu Zhengei, Wang Dunqing, and, of course, Feng Zikai. “The association helped to solidify the loosely organized network of artists that made up the comics industry,” argues Wong in HK Comics, “and it encouraged efforts to raise the quality of its products.” Indeed, the Chinese artists not only used the organization to better their art, but through it explicitly defined Manhua as an art-form and a nationalistic enterprise. Like most nationalistic enterprises, Manhua came to define itself in opposition to other nations; namely Japan. At the Shanghai Animation and Comics Museum the association’s emblem hangs proudly near the entrance with an explanation:

“The association’s emblem is a Cartoon Dragon, representing a caricatured dragon awakening, taking off, determined to fight for the future of the homeland. Members of the association played a leadership role in the cartoon circle at that time, acted as hardcore force in cartoon creation and initiated many periodicals.” (Text from Display)

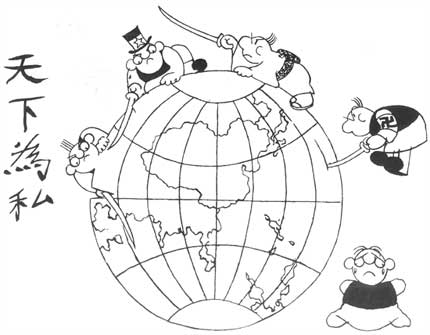

The dragon awakened within the pages of Chinese cartoon magazines and newspapers alike in the 1930s, determined to fight for its homeland at the start of the Sino-Japanese War. In this especially heated time, many artists became popular for creating anti-Japanese characters. One such artist was Huang Yao, who developed the character Niu Bi Zi. Here is perhaps Yao’s most famous cartoon, which depicts Niu Bi Zi (as China) helplessly crying in the wake of the West’s selfish gutting of the world:

Image via Lambiek

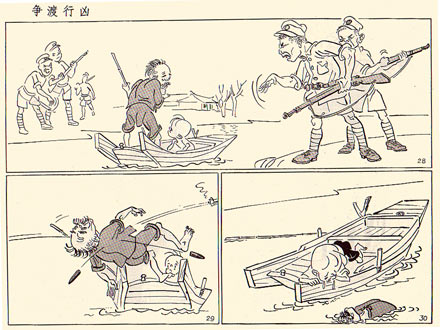

Then there is Zhang Leping, one of the most revered Manhua artists of his generation who is best-known for creating the cartoon character”Sanmao.” For decades the very popular Sanmao represented the struggle of the Chinese people and helped expose the cruelty of occupying Japanese forces. Take for example this typical anti-Japanese Sanmao comic, which shows the Japanese soldiers as senseless and ruthless killers.

Image via Lambiek

The members of the Shanghai Cartoon Association stoked the nationalist flame of China with hatred of Japanese, a fuel source that the PRC has repeatedly used through history when needing to drum up nationalism quickly. The work of these mainland artists from the 1920s until the early 1950s distinguished Manhua from Manga, seemingly putting the two countries in a race for regional dominance in the world of comics.* Today, it takes just one foot inside a Manhua store in any Chinese city to see that the two-way race was won by Japan long ago.

This all leads me back to Cult Youth, an independent Beijing-collective who at first blush looks like a 21st Century incarnation of the Shanghai Cartoon Association. I discovered Cult Youth through this short documentary of them floating around online:

(Click For Video)

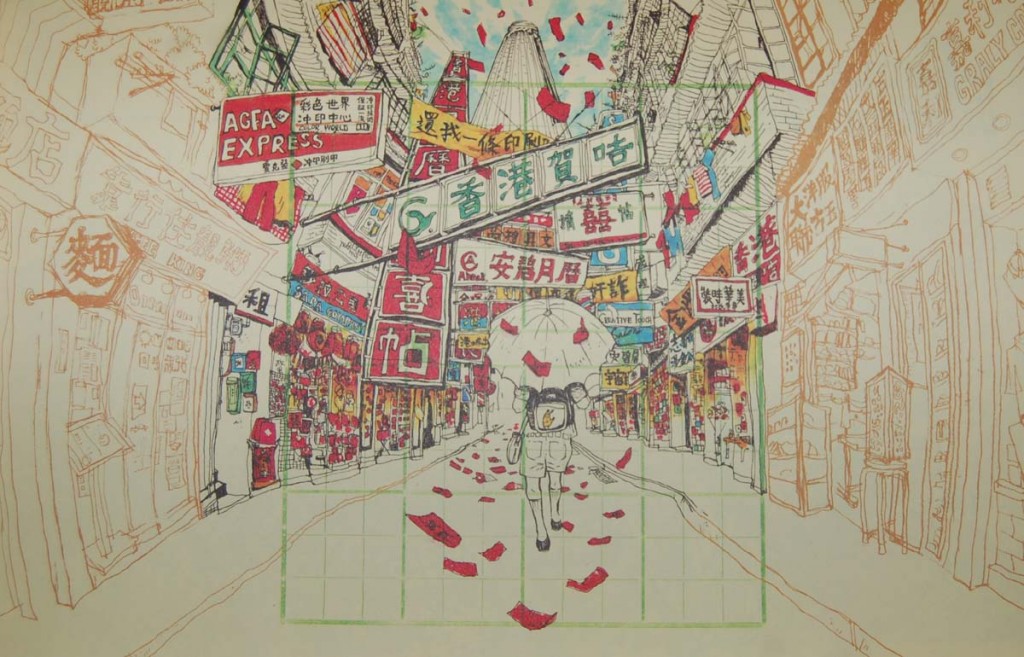

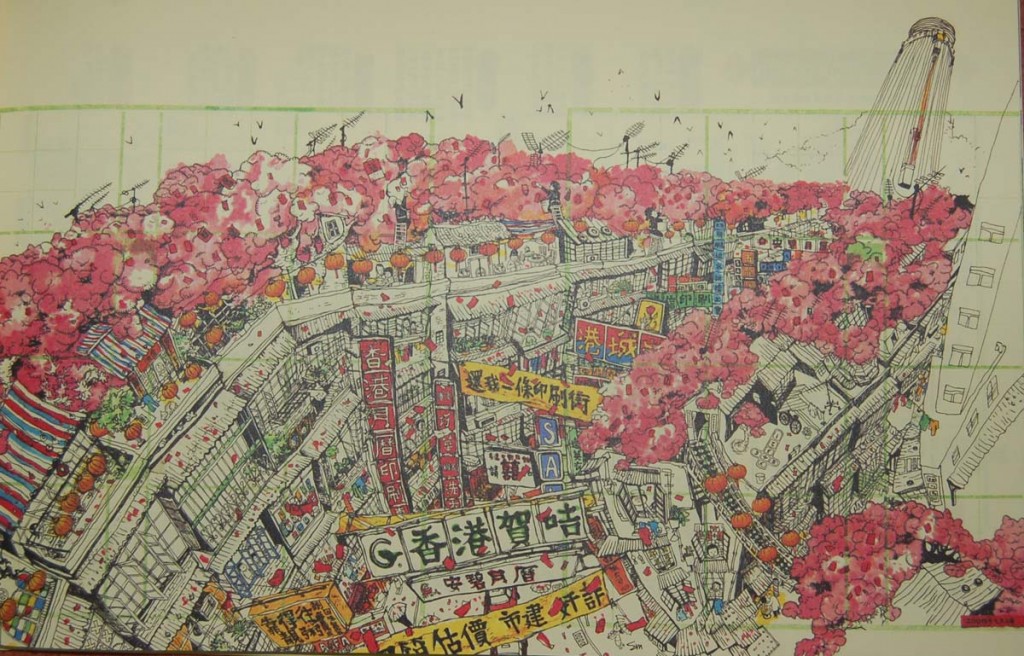

Just like the Shanghai Cartoon Association did in the 1920s, Cult Youth have formed a community built around making (and re-defining) Manhua. A productive community at that: since 2007, Cult Youth has self-published three jam-packed collections of work that they sell online. They come across as a rare creative force in an otherwise stagnant market, willing to embrace “DIY” touchstones and break a few rules in the name of putting out relatively provocative comics. “If you were not born in the 80s and couldn’t decode the plots, then give up! This is not for you!,” reads the CY manifesto at the video’s start, “this is a new generation free of the reasons and worries of the past.” In the context of mainland China this bold self-determinative statement feels radical (at least to an outsider like myself). Which is why when I finally met founding member Chairman Ca I was expecting him to embody the language of young revolutionaries, when in reality he was much more modest about his ambitions.

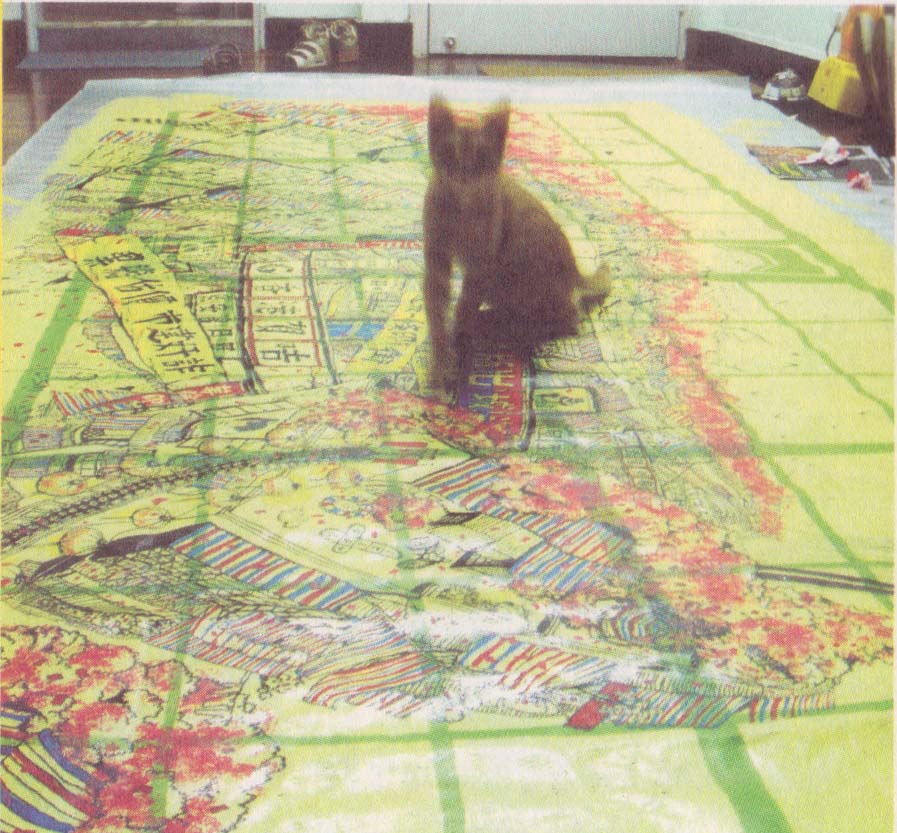

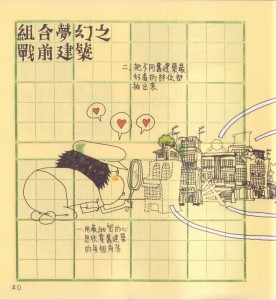

Chairman Ca in his studio.

In my interview with Ca, he politely deflated my suggestions that maybe China was on the verge of a new comics renaissance. Instead, he explained that for him comics are more about a group of friends having fun on the side of their day-jobs, not a potential career path. Ca is an immense talent who has been actively making comics and other art since his days in university, yet he doesn’t keep a portfolio because he doesn’t feel like he needs one. When I asked him about the influence of luminaries like Feng Zikai or where he sees himself in the larger continuum of Manhua he gave me an unexpected answer: “Growing up here we come into contact with more Japanese comics. Only after the Internet became prevalent did we learn about European or North American comics.” Which is to say, the major influences of Ca and Cult Youth’s creative aspirations are not found in the history of Chinese comics, but downloaded copies of R. Crumb and translated Manga. Where the forefathers of Manhua defined themselves in opposition to Japan, Ca represents a generation that defines themselves in collaboration with Japan.

According to Ca the prevalence of translated Japanese comics in today’s market arose because while Manga was establishing itself as an industry in 70s, 80s, and 90s, independent comics were ostensibly made illegal in mainland China. Meanwhile, while the mainland had run dry of original content, Japanese publishers responded to a continued demand for comics in Taiwan and Hong Kong by translating Manga series into Chinese. Hence, Ca and his peers grew up in the mainland with the only new comics available in their language being pirated Manga translations from Taiwan and Hong Kong. Ca’s reference points are then Western reference points: Rockabilly was his first musical love, Zombies are cool, and he identifies philosophically as a Existentialist. For Ca, the fact that Japan is the chief-purveyor of comics in the region isn’t a cultural defeat as older generations would understand it, but simply a reality.

“The industry does well there, it has certain principles and successful cases. It’s easy for young people to turn themselves into that comic industry because it’s an established business,” says Ca of Japan’s Manga market, “For a Chinese person to make a living out of comics it takes a lot of resolute determination to get there. Maybe too much.” Ca’s stance exemplifies a generational shift in Chinese society in the wake of Mao. A generation who now unabashedly embraces Japanese culture through Manga is perhaps the logical extension of Deng Xiaoping’s market-oriented reforms from 1978 onwards: for better or worse, China shifted from a self-contained market to a interdependent player in the world’s economy by opening up. It appears that in the last twenty years the definition of “Manhua” has itself opened up. No longer in a vacuum where it is used as a political tool to encourage nationalism, Manhua is now a term that encompasses a rich history, a translated marketplace, and a few stray youths.

—-

* The 1950s marks the formation of the PRC by Mao, and the point where innovative Manhua fled with many Chinese to Hong Kong. While Manhua continued in the mainland during the twentieth century, it was mainly in a bastardized and government sanctioned-only form unlike its early creative years.

A very special thanks to my friend Alec Sugar who served as my fearless translator during the Chairman Ca interview.

And one more Zikai for the road: