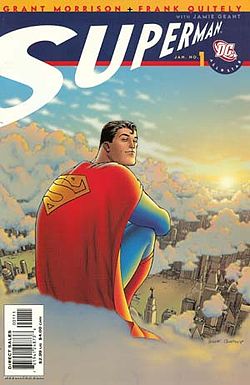

A while back I expressed skepticism about All-Star Superman; Marc Singer replied with a long and eloquent defense, which I’m reprinting here. His comment is below.

Thanks for the link and the comments, Noah.

Your point about ideals without content is well taken, but the call for placing superheroes in “some sort of coherent moral framework,” particularly the point about superheroes skirting “political or social engagement,” seems a little musty, a bad leftover (or hangover?) from the eighties. Comics have been doing that for twenty years, and they usually reach the same tired conclusions about fascism (Animal Man being one of the rare exceptions). It’s to Morrison’s credit that All Star Superman largely avoids that well-worn path. With the exception of Luthor, he avoids talking about crime and justice; maybe one or two other criminals appear in the series and they hold absolutely no importance. Decoupling the superhero comic from these serious, meaningful discussions of law and order, most of which end up with a guy in a costume hitting another guy in a costume anyway, is probably one of the freshest moves Morrison makes.

That isn’t to say he avoids the other issues you raise. Issue #9 tackles that hoary old idea, the fascist (or at least cultural imperialist) superman, and finds him wanting. But what superhero comic in the last two decades hasn’t tackled it? This is one of the reasons I was left so cold by the issue, until subsequent ones made it clear that the comic was doing another job as well, motivating Superman to increase his commitment to a different set of ideals.

What are they? As seen in the last four issues in particular: compassion (even for his rivals or enemies), forgiveness (ditto), progress (particularly through scientific research), responsibility for others’ well being, curiosity, creativity, and a commitment to put these other ideals into action. These aren’t tied to any political ideology, but they absolutely are ethical stances (and some of them, like Superman’s commitment to building a better future through scientific progress, imply certain political ideologies, at least in our current cultural moment).

No, this is not a party platform and it doesn’t offer the kind of explicit political engagement you call for. I’m not sure that a Superman comic needs to, for some of the very reasons you list. Superman is a long-lived character with a cultural meaning much larger than any one political ideology (even the two-fisted New Deal liberalism he started out with). Tying him down to a single politics would be both difficult and reductive, especially given the premise Morrison has chosen for his project–synthesizing all prior versions of the character into a seamless whole.

Superman now stands for a kind of general, free-floating concept of decency and inspiration, as seen by all those Obama comparisons I linked to in the previous post (and the many, many more I did not link to). It’s not tied to ideology, but to idealism–Obama’s fans see him as a good guy, as one of the most openly moral figures in liberal politics in decades, as someone who inspires their own hope, so they post a photograph or a video that explicitly compares him to Superman. QED. Superman has become one of the first figures our culture calls to mind when we thinks of these traits. (The other being Jesus, and Morrison does not shy away from Christian references and narrative structures any more than Obama or the Daily Show shy away from manger jokes.) Morrison did not invent this trait, obviously, but he knows the character comes with it and he’s chosen to make it the centerpiece of his comic, building his ethical argument where the character already stands.

The line about having to invent Superman ourselves was a too-cute reference to something that happens in issue #10, which attempts to supply the tradition you say he’s lacking. I have to agree with Nick–I think your post would have been written very differently had you read the last half of the series, especially the last four issues, where all this plays out. Which is not to say you would have liked it, but you would find it hard to say the comic doesn’t articulate any ideals or place anything at stake. Any vagueness in my review is mine, not Morrison’s. But then, an eloquent apologist would say that. :)

Actually, that may be the biggest error in your post–I don’t see myself as an apologist, eloquent or otherwise, because I don’t see All Star Superman as having anything to apologize for.