We are all reeling from the recent, devastating attacks in Paris that claimed the lives of too many and changed the lives of many, many more. The attacks were carried out on behalf of Daesh (ISIS), the chaos being another stake to further drive away reasonable discourse and chances at real communication. A day before these attacks, Beirut—with only a whisper in the media—suffered a similar fate at the hands of Daesh.

In the middle of this, a comics anthology with roots in Beirut and many ties to French-speaking Europe fights to keep its doors open, its mission is to open worldwide communication without national borders. They may buckle under the weight of censorship.

The irony here is notable, to say the least.

Samandal is a French, English, and Arabic language international comics anthology, in production for a decade. It is funded by the Belgian publishing house L’employé du Moi, the French Cultural Center in Beirut and the Belgian Ministry of Culture in Brussels, but it is on the brink of collapse due to charges that it has contributed to sectarian strife.

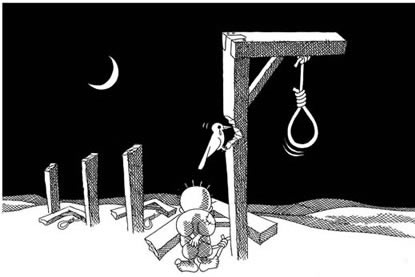

Back in 2009, Samandal released its seventh issue, titled “Revenge.” In this particular issue were two comics that, according to the comic’s editors, were taken out of context and reported to the Lebanese authorities.

In the first comic in question, “Lebanese Recipes for Revenge,”—created by Lena Merhej, who is also one of Samandal’s editors—common Lebanese phrases (analogous to English phrases like “go eat shit” or “buying the farm”) are illustrated literally. The phrase “May [God] burn your religion” is portrayed with a Christian and a Muslim being doused with gasoline and lit with a match.

The second comic, created by Valfret, is titled “Ecce Homo.” It follows the story of a Roman centurion who has drunken sexual relations with a legionnaire. The legionnaire is killed by the centurion due to his own disgust, and the centurion then leads his army to a Christian sect in order to pin the murder on someone else. The very last page of this comic is a scene of a crucified member of that Christian sect, with the centurion thinking to himself, “It’s you who’s gay.”

These two pages were flagged and investigated due to complaints lodged by unknown Christian figures, “expressing their disapproval concerning the publication of some comics … that are offensive to the Christian religion.” In an unusual move, three of the four editors of Samandal—not the artists who created the comics—were accused of wrongdoing. Take into consideration that Merhej is an editor herself, and things seem even more puzzling.

After several years of court cases, the results are not good. Samandal has been found guilty and must pay 30 million liras ($20,000) in damages, wiping out their savings and threatening them with extinction. Unless they receive an infusion of cash, their next book, Geographia, is slated to be their last. In response to this, Samandal has launched an Indiegogo campaign to fund the publishing of two more books. As of this writing, there’s still time to contribute, and plenty of money needed.

Why is this important?

Samandal is truly a worldwide institution. How many comics anthologies have you seen that are in multiple languages? It’s a fantastic microcosm of the alternative comics trend outside of the tiny, tiny American market. In the “Revenge” issue alone, I see contributors hailing from France, Belgium, Quebec, Lebanon, the United States, South Korea, and the United Kingdom.

I’m a big believer in open communication. In the face of such travesty, the way to truly “win” is by talking more, opening more channels, being more in touch with the world. Samandal has always embodied that universal spirit to me. What better time is there to reinforce that speech should remain free?

Please consider donating to the Indiegogo campagn and check out their website for more information on the case.

Lastly, here’s Merhej’s comic describing the scandal, in her own words. Take it away, Lena:

A number of years ago, I had the pleasure of speaking to a group of young artists at the Museum of Comics and Cartoon Art. It was spectacular evening, and I’ve made a point of keeping in touch with several of the talented young people I met there. A few years later, at the annual MoCCA event, I ran into one of those young artists, Marguerite Dabaie. She handed me a self-published comic about transvestites during the Weimar Republic. I was instantly hooked by her personal style of story-telling that communicated emotion, without beating you with it.

A number of years ago, I had the pleasure of speaking to a group of young artists at the Museum of Comics and Cartoon Art. It was spectacular evening, and I’ve made a point of keeping in touch with several of the talented young people I met there. A few years later, at the annual MoCCA event, I ran into one of those young artists, Marguerite Dabaie. She handed me a self-published comic about transvestites during the Weimar Republic. I was instantly hooked by her personal style of story-telling that communicated emotion, without beating you with it.