I began writing this piece before the announcement of the depressing verdict in the case between the Estate of Jack Kirby and Marvel Comics and by consequence Stan Lee. In the simplest terms, Marc Toberoff, the Kirby Estate’s lawyer claimed Kirby was the originator of all the properties in question. Toberoff’s strategy was the same as that he deployed for the heirs to the Superman creators Jerome Siegel and Joseph Shuster in their fight to reclaim copyrights from DC Comics, a division of Warner Brothers Entertainment. He lost. Even the most ardent Kirby fan acknowledges that for a while the two men, Kirby and Lee, collaborated comfortably to produce seminal comics in the American canon and all but a few claim that to make Kirby the sole creator across the board is not defensible. The Kirby lawyers overstepped the mark in the attempt to regain control of early copyright and collect remuneration for the proceeds from early works that were subsequently developed. For those of us on the sidelines, perhaps more painfully the result legally diminishes Kirby’s place in history.

All parties have been less than candid in their presentations.There is plenty of blame to go around, which I am forced to say even as an artist and long time supporter of the Kirby camp. The result of this case will affect all who deal in creative and intellectual property, whether literary or otherwise and unfortunately the Kirby lawyers mishandled what should have been a landmark case in the protection of creative properties.

Some suggest that Kirby himself signed his rights away when he agreed to create as “work for hire,” but I would point to a parallel in the music industry where early recording artists similarly originally gave up their rights. They later won cases to reclaim them because they could not have foreseen the new media that would offer alternate distribution platforms and uses for their creative property. Contract law, which to validate any agreement depends on a “meeting of the minds,” might be applied as Kirby could not reasonably have imagined the rapidity and growth of media technology. Kirby though often accused of having an overly vivid imagination when it comes to Sci-fi, was not actually clairvoyant.

The shambles that has ensued after Lee’s courtroom default from history because of his contractual and financial allegiance to the company leaves the creative world a sadder place. Revisionist history diminishes all. This dispute between artist and Marvel is sublime in its scope. The immense edifice of the corporation dizzies the individual.

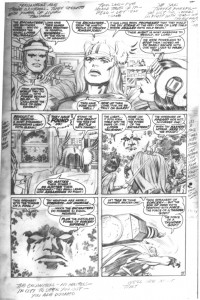

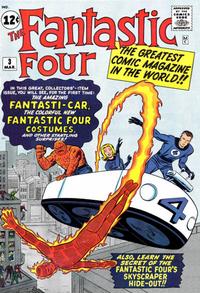

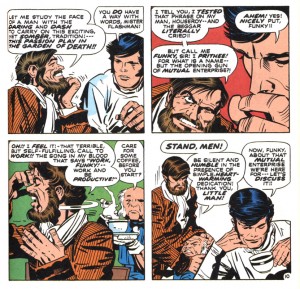

The team's creative frisson as written by Jack Kirby from Fantastic Four Annual 5, 1967.

Another aspect of this debate, which has become so reductive in its claims of creative primacy, suggests that the idea is the only criteria for original creation. Even if hypothetically Lee originated characters, I would argue that where there is no previous model then the artist creates the image and reifies a concept. If there is no model to work from, then one must create the original figure, which henceforth will become that model. Pushed to a logical limit, one could point to the fact that though Bernini did not originate the myth of Apollo and Daphne, he certainly produced his original sculpture. His rendering of the narrative is creatively unique.

Apollo and Daphne by Bernini

On the other hand, in the consideration of the various statues of “David” created by numerous artists, Donatello, Michelangelo and Bernini for example, one might say that these are all “works for hire” and only the divine source of the narrative is significant, with the plot supplied by the church. The church, like any other giant institution or corporation has interests in controlling its mythologies. This labor, artistic or not is at the service of a larger ideology.

Donatello's David offers a model sheet in 3D.

As Louis Althusser, a psychology-driven sociologist says, “assuming that every social formation arises from a dominant mode of production, I can say that the process of production sets to work the existing productive forces in and under definite relations of production.” I shall return to Althusser momentarily, but for now I wish to affirm that both Kirby and Lee were proud to work within the ideology of American capitalism. In the legal case, neither side stands or challenges American capitalism on ideological grounds overtly, despite a strong undertow of class and labor issues that largely go unspoken. And while I have framed many of the issues within the sphere of artistic production, certainly both Kirby and Lee saw themselves in the business of selling comics. Elsewhere, Althusser helpfully casts light how problems might arise undetected by two men who had not only served in the military as a system of American ideology, but had become a part of the means of production for that ideology.

Ideologies are perceived-accepted–suffered cultural objects, which work fundamentally on men through a process they do not understand. What men express in their ideologies is not their true relation to their conditions of existence, but how they react to their conditions of existence; which presupposes a real relationship and an imaginary relationship.

Kirby perhaps presupposed himself a participant in a post WW2 America that had fought and earned the right to play fair. He imagined that a handshake would suffice as he saw himself a part of an institution that in reality would later belittle his role. Lee working in a family business, saw himself as management rather than worker and this self-elevation transferred to how he interpreted his creative relationship, which gave more import to words, as though they signified his class and its rights and its sanction.

In comics, men of words hire men of images. The historical system of patronage is codified by capitalism and is supported by critics who use words and instinctively “read” comic text as though it is merely supported by images that stand in for verbal metaphors. In the arena of commercial art, class ties to and debases visual literacy and text reigns supreme. (Comics are annexed from Art History, which might disrupt labor relations by elevating the artist in relation to the writer. This would threaten an instiutionalized ideology in which the journeyman artist is kept in his imaginary place.)

Terry Eagleton expresses another intersecting perspective that helps illuminate how the comics industry positioned itself in a self-perpetuating Western capitalist society:

‘Mass’ culture is not the inevitable product of ‘industrial’ society, but the offspring of a particular form of industrialism which organizes production for profit rather than for use, which concerns itself with what will sell rather than with what is valuable.

Kirby and Lee became engaged in a culture that conflated their cultural output with their commercial product. Their value as artists was secondary to their commercial potential. This is a trap that concerns all work in the arts and in scholarly fields as the pressure to deliver a “product” can easily obscure the “value” of one’s work. Kirby and Lee worked within let us say, “popular” culture and there were undoubtedly certain sacrifices to deadlines. However it would be difficult to imagine that either worked deliberately below his potential “in the definite relations of production” of their industry and society.

Longinus on Where Words Count, Stan Lee as a Prince of Rhetoric.

I had intended with the second in my series about the sublime and comics to return to the (fragmented) work of Longinus to help elucidate the relationship between Kirby and Lee. Longinus, a Greek teacher of rhetoric or a literary critic who lived in the 1st or 3rd century AD, wrote a treatise “On the Sublime,” which discusses language in relation to the production of the sublime. His observations, which are delivered in the form of a letter, in fact represent the underpinnings of a textbook of advice for the writer and probably speechgiver, on the creation of sublime text, though much of this latter advice is lost. His interest is in identifying and delineating the elements of writing that operates in the presence and construction of sublime language and pointing out the pitfalls that can derail the would-be rhetorician. He offers:

The Sublime leads the listeners not to persuasion, but to ecstasy: for what is wonderful always goes together with a sense of dismay, and prevails over what is only convincing or delightful, since persuasion, as a rule, is within everyone’s grasp: whereas, the Sublime, giving to speech an invincible power and [an invincible] strength, rises above every listener.

Longinus further says the sublime rhetoric of the speech-writer resides in “great thoughts, strong emotions, certain figures of thought and speech, noble diction, and dignified word arrangement,” which might also begin to expose possibilities in the interactions between words and ideas in comics. All of these elements one would hope to discover in the pages of a heroic narrative of the superhero comics, but might be particularly explicit in a production such as Jack Kirby and Stan Lee’s “Thor.”

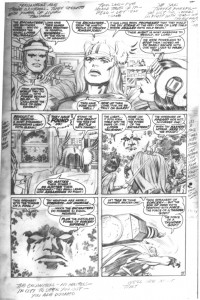

When I presented the Kirby /Lee “Thor” page in my previous discussion of the sublime, I did not address how the notes in the outside borders written in Jack Kirby’s hand might inform the final text/speech in the finished word balloons written by Stan Lee. Here on face value, it appears as though the initial “ideas” and their visual rendition come from Kirby, but are reconfigured by Lee. Lee’s diction transforms Kirby’s side notations with amplified language and words that are of a suitable weight to match the visual narrative and content. This is achieved as he uses repetition and emphasis to create a heightened language that inspires and moves the reader. Thor and his cohorts never articulate outside of their quasi-archaic parlance.

For the reader, the strange tone and historicity add weight to the narrative. This language is that of great men doing great things. Most of us as youth ( although I except that somewhere there are probably religious groups who still use the “thee” and “thou” of second person singular ) only experience this type of highly wrought diction in the formal realm of “literature,” as in Will Shakespeare and John Donne, or in the script of the Bible. Lee’s écriture, the grammar of which delightfully and frequently deviates from recorded “English” & its real variants is meant to be understood as a heroic language and it is Lee’s generosity of style that allows the reader to formulate this language internally in his or her own linguistic terms. In other words, one is able to participate imaginatively in the construction of the characters’ syntax and diction. Further, the reader is able to engage and even deploy the system of language, to think without fear of error within the construct of Lee’s linguistics. The effect would be comical beyond its acceptable level of dramatic kitsch if the entire comic were to be spoken in Kirby’s New York slang circa the Bowery Boys. As the language is transformed by Lee it is able to support its authority within the ideological tenor of received historicity.

All the same can one say that Lee is dangerously close to the ridiculous, but that as children this giant nuance escapes us? Perhaps his flexible English reinforces an independent American ideology and the desire to escape from the vestiges of British ligusitic tyranny, or to become a “noble” American writer.

In the border notes in Kirby’s recognizable hand, “Thor says – I’ve heard tales of it – well—let em come,” written clearly in the American mid-century vernacular. This is transformed by the rhetorical skills of Lee who gives: “The Enchanter from the mystic realm of Ringssrjord!…It has long been prophesied that they would one day strike at the very core of Life itself where Asgard doth hold reign!” Issues of class manifest themselves in the “superior,” declarative language of the Gods. The vernacular of Kirby’s voice must be corrected to reflect that of the upper class heroes.

Both men recognize their own class in relation to the content. Kirby, who remained proud of his heritage as the son of a Lower East Side immigrant, does not write his text in “Thor-speak” but uses his working class action voice to express his ideas. This forces questions about how class operated between the men. Implicitly, art is produced in a strangely abased position in the social hierarchy of production. Art appears to be the tool of the intuitive, untamed mind, while writing evidences intellectual precision and authority. Logocentrism is bound to class structures and it seems Thor-speak claims the authority of the noble class and that its writer represents a conduit to this class with its values of duty and honor. Remember as Longinus says: “The great speech maker speaks great thoughts.”

In his essay “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses,” Althusser suggests capitalist society reproduces the relations of production in such a way that this reproduction and the relations derived from it are obscured. Capitalist exploitation hides its presence from direct sight, but the ideology of capitalism, which is imaginary, interpellates us in such a way that we recognize our place in that ideology and accept the rightness of it. This occurs through a series of erroneous recognitions and assumptions that follow a fallacious logic… It must be so because it must be so, right is right and so forth. Althusser’s explanation of this process runs: Ideology calls out to (or hails, interpellates) individuals. A (metaphorical) illustration of this: Ideology says, “hey, Joe” and Joe responds, “Yes?” In doing this, Joe recognizes himself via ideology, situates himself in the position it tells him he is in. Since he knows he is, in fact, Joe, just like Ideology says he is, ideology seems natural and obvious, not ideological.

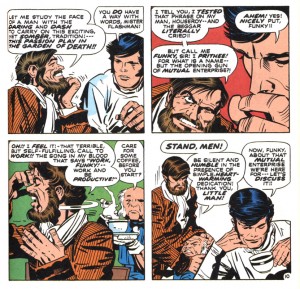

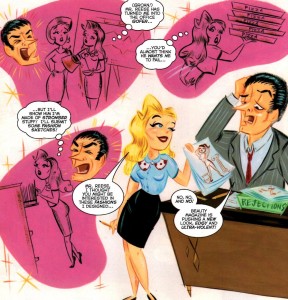

Kirby scripts Stan Lee's dialogue as Funky Flashman with Scott Free in Mister Miracle 5, November 1971.

In the panels above, Funky Flashman tries to manage Scott Free, who suggests that they collaborate on a mutual enterprise. Flashman internalizes and operates within the ideological system, even as he toys with transgressing boundaries which he would like to assault through language. Further, he uses words as a device of control, he does not recognize his own position within the ideology. Flashman describes how his words elicit emotion and comprehends this advantage as one of power. He ironically recognizes himself as a subject and self-imposes through pleasure and duty his own imaginary inherited desire to work. “Oh I feel it the terrible, self-fulfilling call to work!! The song in my blood that says “Work Funky!!! Work and be productive!”

Kirby as the writer of this text, lampoons the writer, a thinly-veiled depiction of Lee, and frames Flashman as an effete, decadent. But his mockery does not release either from the cycle of production. Althusser states that free will is essential for this continual state of self-delusion (false consciousness) to persist. The subject must feel that he is free to act as he chooses, but his self recognition within the social structure ensures that he will continue to be productive and remain within an ideology that he believes he has created and sanctioned. As we read comics we are identifying ourselves as within an ideology. Whether as adult readers we see comics as escapist “lower” literature, a developing underserved art form, or we read them as kids and adults who internalize their ideological positions, we recognize a cultural production when we look at and read a comic and as such we have agreed to become part of the Ideological State Apparatus.

Althusser suggest that capitalism is held in place by Repressive State Apparatuses (RSA), the Law and State. As in Marx, Althusser posits that a superstructure of political and legal repressive systems stands on an economic infrastructure with repressive state edifices (RSA) supported in turn by Ideological State Apparatuses (ISAs). ISAs are found in the educational system, the religious system, the family, the cultural systems of literature, the arts, sports. While the RSA controls by force, the ISA functions through promises and seduction. Althusser suggests that education is the dominant ISA, because school teaches “know-how” wrapped in the ideology of the ruling class which enbles the subject to adhere to their role in class society. Althusser further notes that children are given into the hands of institutions of education to be indoctrinated for years, from pre-k -til…well some of us never leave.

Without making this a full blown discussion of Althusser, one can draw from his position the idea that a subject freely submits to subjugation through ISAs. The Flashman and Scott Free passage points to the irony of the belief in “work” creative or otherwise, yet simultaneously recognizes the value of work as inherently worthy. Scott Free promotes a silent acceptance of the workingman’s role, while the entitled Flashman proclaims about the difficulties of creative work.

As readers of this passage we willingly accept the need to fulfill our role as workers, even as we privilege class and even as we admire the nobility of the work ethic. Intriguingly, as readers we willingly identify with Scott Free, the self-recognized “actual” worker and accept an appellation that sets us within the mythologization of honorable worker. The comic book here is an ISA, by which we willingly reinforce statifications of class and labor, which directly maps on to how we prioritize text over image. The debate that surrounds Kirby and Lee slips past any consideraton of equality of medium into issues of class and artistic stratifications.

Colonel Corkin’s Sublime Call to Capitalism.

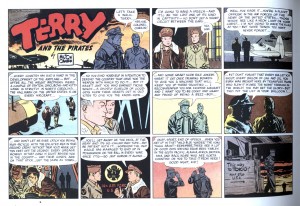

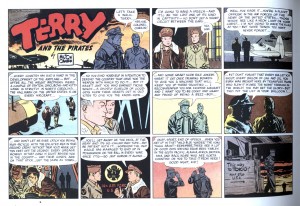

Elsewhere the rhetorical power of comics literally moves from the page into the Congress as the wartime Terry and the Pirates’ Colonel Corkin speaks to his young charge a speech of such sublimity that it moves the reader who cannot help but respond to the noble sentiments expressed. This at least is the opinion of the Hon. Carl Hinshaw of California, who addressed the House of Representatives on Monday. October 18, 1943. Here the comic is celebrated as a vehicle of ideological repression. Hinshaw s remarks follow thus:

Mr. Speaker, I have long been addicted to scanning the so called comic strips that appear in our daily and Sunday papers. I have followed the careers of the characters, such as Uncle Walt and Skeezix, Little Orphan Annie, Sgt. Stony Craig, and others for many, many years. Among these characters the most interesting and exciting of them all are Terry and Flip Corkin. On yesterday, Sunday, October 17, Milton Caniff, the artist, presented one of the finest and most noble of sentiments in the lecture which he caused Col. Flip Corkin to deliver to the newly commissioned young flyer, Terry. It is deserving of immortality and in order that it shall not be lost completely, I present it wishing only that the splendid cartoons in color might also be reprinted here. The dialog follows:

Milton Caniff's Terry and the Pirates moves from ISA to RSA.

It is primarily the dialogue that counts for the Congressman, though he responds to the overall novelty of the cartoon and its sentiments. In the comic, the uniformed, everyman hero reaches a sublimity that moves beyond the “normal” linguistic constraints of his class. Spurred by duty and patriotism Colonel Corkin is able to raise his diction to one that moves and inspires. He is sublime. His speech to Terry through the vehicle or mechanism of heroic diction outlines Terry’s place in the system of production as a part of “something” larger. The passage offers an ideological rationale for capitalism, through the aegis of classical values. Honor and glory inform one’s duty to engage the state as a function of the larger industrial war complex. All of which alerts the reader to the ability of cultural institutions to move into the service of instruments of state repression. In panel nine, the drawing reproduces a government logo, a trademark of America the corporation, which supports the text. Terry the innocent, is educated by the Platonic wisdom of Colonel Corkin in an easily recognizable trope of “high class” wisdom. In the last panel, Terry walks in the direction indicated by the textual sign: “This way to Tokyo, Next stop U.S.A.” His hands are bound in the constraints of his pockets in a self-imposed gesture of submission and passivity.The sublime language moves us into alignment with the government position which not only requires courage in the face of adversity (the merits of WW2 are not in question here,) but also requires that structures of class are concretized and accepted in order for Terry to behave honorably.

The depth of the RSA's gratitude.

“On April 3, 1989, on the first anniversary of Caniff’s death, the Air Force officially discharged Steve Canyon from the service and presented his United States Air Force discharge certificate, service record, flight record, personnel file, and this shadowbox featuring Canyon’s service medals to the Caniff Collection at The Ohio State University.”

Originally, before the Kirby /Marvel result, I had intended to offer this passage about “Terry and the Pirates” as evidence of the power of the sublime as a political tool and to discuss the slippery parameters of cultural institutions and government bodies. I wanted to interrogate how diction in comics elevates or otherwise shapes response and meaning. In the end, the colonization of the Colonel Corkin speech by a government representative suggests that elevated diction is recouped by the ruling class, even in the ambigous guise of applause. Rhetoric, especially sublime rhetoric is a commodity like any other; it is a currency in the capital of the state and its many means of self-reproduction. For the moment, the comic image is undergoing the same recoupment as its rhetorical counterpart. Its value and its final place in American ideology will continue to be down played until its full financial worth can be ascertained. The constantly evolving new medium of technology and the fiscal world of “not as yet ripe for deals to be sealed” offers a climate of uncertainty for those who would capitalize the image.

Kirby ‘s work cannot be valued: the market is not ready.