Noah, I’m guessing your mixed feelings on your first read of Left Hand of Darkness had something to do with the fact that the male protagonist and his androgynous companion never consummate their relationship. Setting aside the fact that the book was written in 1968, I think it would have been weaker if they had “done the deed” and possibly lived happily ever after. The fact that the protagonist is left to live with his regrets makes it all the more realistic, and, for me anyway, that much more powerful.

____

This is part of the Gay Utopia project, originally published in 2007. A map of the Gay Utopia is here.

Tag Archives: Matt Thorn

Voices From the Archive: Matt Thorn on Jack Kirby

Translator and manga scholar Matt Thorn replied to some of my thoughts on Jack Kirby a while back. I thought I’d reprint his comments here (I’ve added some markers just to make it clear who’s speaking.

[Noah:] He [Jack Kirby] draws awesome monsters, though. Which is no small thing, and which I really appreciate about him.

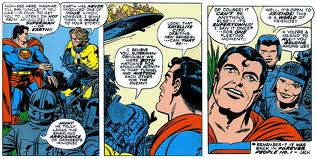

Matt Thorn:What you said. Kirby was much, much better (IMHO) at drawing the ugly and grotesque than at drawing the beautiful, which is probably why D.C. took the embarrassing step of having someone re-draw Kirby’s Superman. I prefer Kirby’s take, but the whole thing about Superman is that he’s all shiny and handsome and sparkly, right? Kirby’s Superman looks like a college wrestler with a chip on his shoulder. Which is very cool, but, yeah, not the image of Superman D.C. wants to convey (then or now). The Thing is probably the character that is most iconically Kirby in my mind. Grotesque, and yet sympathetic, and somehow just very cool, in a very anti-Superman kind of way.

[Noah:] Haney’s not subtle, and the quality varies obviously. But he’s way more attuned to a world outside his skull than Kirby is.

[Matt Thorn:] Noah, I think you nailed it there. Kirby seems unable to successfully step outside of the world inside his own skull. His half-hearted attempt to write “groovy slang” illustrates that he didn’t know much about or really care much about the world outside his skull, at least not after WWII. And that is of course fine. As others have noted above, many great artists are enormously successful at being what I controversially characterized as “self-indulgent,” and what Mike more generously characterized as doing work that is “personally meaningful to them.” Whether you see it as a feature or a bug, I think it’s fair to say that Kirby’s worlds are more or less self-contained, and while they may speak to “the human condition” at large, he was never one whose work really reflected the world outside his door.

Which, AGAIN, is PERFECTLY OKAY.

Voices From the Archive: Matt Thorn on Bianca and Other Moto Hagio Stories

Matt Thorn, the translator and editor of Moto Hagio’s Drunken Dream from Fantagraphics, commented on a number of my posts about that volume. I thought I’d reprint one of his discussions here.

Wow! I just found this today. Sorry to come so late to the party. I’ll respond to your reviews the same way you did to the stories, i.e., as I read them.

I don’t want to argue the merits of the works, because if you don’t like something, you don’t like it, and no amount of exegesis can change that.

But just some factual clarifications. 1977 is the *copyright* date of the first stories, not the year they were published. “Bianca” was published in 1970, when Hagio was 21, but was actually written/drawn a year or two earlier. “Girl on Porch with Puppy” was published in 1971, when Hagio was 22, but this one, too, was actually created a year or two earlier. “Autumn Journey” was also published in 1971.

And now for some cultural/historical background. This was a time, both in Japan and throughout most of the developed world, when youth culture was pretty melodramatic and more than a little self-indulgent. Things that seem clichéd and embarrassing today were seen as “real, man,” and the kids could “grok” it, you dig? Just think about “Easy Rider.” It is worshipped by Baby Boomers as anthem of their generation, but most young people watching it today would probably think, “What the hell are these people doing and why the hell should I care? And what’s with the random redneck drive-by shooting ending?” The Baby Boomer response is, “You had to be there.” Ditto for these stories. Perhaps I should have written a brief introduction to each story in order to provide this sort of context, but it never occurred to me, probably because I’m too close to the work.

As a social scientist (of sorts), this context is interesting to me, and it is a matter of historical fact that these stories were considered to be groundbreaking and fresh in the world of shoujo manga, and were extremely influential. If you’re going to measure them against something, it would be more fair to measure them against 1) other shoujo manga of the day, or 2) English-language romance comics of the same period, keeping in mind that the target audience here was considered to be girls aged 8 to about 15.

On a personal level, I chose these stories not only because Hagio aficionados consider them representative or her work at the time (they are), but because, 1) “Bianca” is just damned pretty to look at, and showcases her technical skills as a young illustrator (if not storyteller), 2) “Girl on Porch with Puppy” captures the kind of quirky, Twilight Zone, sci-fi/fantasy element that was influenced by such male artists as Shinji Nagashima, but which was practically taboo in shoujo manga of the day, and 3) “Autumn Journey” embodies the vaguely-European adolescent boy romance that was influenced by European cinema of the day, and which Hagio went on to develop in more sophisticated ways, in works like “The Heart of Thomas.”

In short, I wanted to represent her whole career, not just collect a bunch of first-rate stories that modern anglophone readers today can easily appreciate. If I had wanted to do that, I would have selected very different stories, and there would probably be none from the first few years of her professional career.

But, hey, at least nobody dies in “Autumn Journey.”

The Japanese Superman

I did a couple of posts about Matt Thorn’s classic essay, The Face of the Other, in which he explains:

I have given presentations on manga to Western audiences many times, but regardless of the particular themes of my talks, when the floor is opened up for discussion I am invariably asked the same question: “Why do all the characters look Caucasian?” You may have asked yourself the same question.

I answer that question with a question of my own: “Why do you think they look Caucasian?” “Because of the round eyes,” or the “blonde hair,” is the common response. When I ask then if the questioner actually knows anyone, “Caucasian” or otherwise, who really looks anything like these highly stylized cartoons, the response may be, “Well, they look more Caucasian than Asian.” Considering the wide range of variation in the features of persons of both European and East Asian descent, and the fact that these line drawings fall nowhere remotely within that range, it seems odd to claim that such cartoons look “more like” one people than another, but I hope you will see by now that what is being discussed has nothing to do with objective anatomical reality, but is rather about signification.

Still, this can be a hard sell;a cartoon character with wide eyes looks white to us; it’s hard to believe they look Japanese to the Japanese. As commenter awb says:

The article seems to be telling me not to believe my lying eyes. I think he is saying that people are trained to accept the western european look as “standard” or even preferred and because Japan was never dominated by a western society the see themselves as the “standard” and therefore their manga is reflective of that. But, jeez, they don’t look asian! Yes, there are some Japanese without the folds on their eyes and those with frizzy hair but is he telling me the vast majority don’t?

After a whole thread of my constant nagging, awb did eventually (and perhaps just to shut me up) agree to accept Matt’s expert opinion that the Japanese see the manga characters as Japanese. But…it’s not that easy to shut me up. And, moreover, I’ve thought of a really good example to explain how it is possible for the Japanese to see the round-eyed manga characters as Caucasian. So, I give you….the Japanese Superman.

That’s the original Joe Shuster version of Superman, of course. And if you’ll look closely, you’ll see that…he looks Japanese. He’s got dark hair. He’s got narrow slanting dark eyes. Shuster’s ideal man is Asian. An inferiority complex, perhaps?

No, of course not. Even though Superman iconographically “looks” like he could be Asian, we see him as white, because of the context and because our iconographic default is “Caucasian”, even when, as in this case, the signs actually point somewhere else. In Japan, it works the same way, but in reverse; Japanese is the default, and if you want to represent, say, a Caucasian, you have to take some specific steps to get there.

So why is Superman stylized like that? I don’t have any idea, really…but I’d like to think it’s for the same reason that manga characters look “white”. That is, there’s iconographic influence. Tezuka borrowed his iconography from Disney; it’s not impossible to believe that Shuster got some of his iconography from a generalized Art Nouveau illustrational milieu, which was in turn heavily indebted to Japanese prints. Those older prints represent Japanese faces in a way similar to what we still (perhaps influenced by those very prints?) think of as iconographically Asian.

Update: In comments, Tom undoes my elegant theory with a tiny little squiggle. Darn it.

Update 2: But…Mitch defends the Japaneseness of the design. Phew!

Gaijin Love

I’ve mentioned before Matt Thorn’s great article about why characters in Japanese manga are not, in fact, meant to represent, or even to suggest, Westerners, despite those round eyes.

Japan, however, is not and never has been a European-dominated society. The Japanese are not Other within their own borders, and therefore drawn (or painted or sculpted) representations of, by and for Japanese do not, as a rule, include stereotyped racial markers. A circle with two dots for eyes and a line for a mouth is, by default, Japanese.

It should come as no surprise, then, that Japanese readers should have no trouble accepting the stylized characters in manga, with their small jaws, all but nonexistent noses, and famously enormous eyes as “Japanese.” Unless the characters are clearly identified as foreign, Japanese readers see them as Japanese, and it would never occur to most readers that they might be otherwise, regardless of whether non-Japanese observers think the characters look Japanese or not.

… the notion that the Japanese harbor an inferiority complex vis-a-vis the White West seems to me based on the largely unconscious assumption that non-Western peoples envy the West, and more specifically on the American fantasy that everyone in the world naturally wants to be American. Of course, the scholars and intellectuals who note such tendencies in Japan do not applaud it; on the contrary, they cluck their tongues and wring their hands and wish loudly that the Japanese would shun the temptations of the West and remain true to and proud of their heritage. But the eagerness with which they seek out evidence of a desire to be “white,” and the stubbornness with which they ignore evidence to the contrary, suggests to me that their apprehension of social reality is heavily filtered through an unintended ethnocentrism.

Matt points out, among other things, that the characters in the comic are stylized; they don’t look all that much like people of any ethnicity. Definitely read the whole thing if you haven’t already. I found it very convincing.

And yet….well, look at this:

That’s the cover of Japanese Vogue from January, purchased on ebay by my fashion-magazine-obsessed-significant other. Probably the first thing you’ll notice in the picture above is that the woman is clutching her crotch. After that, though, you might observe that she’s not Japanese. Furthermore:

All the covers from Japanese Vogue I found seem to feature Westerners. Most of the interior pictures do too.

(And for those wondering, no, all foreign issues of Vogue don’t feature Western models. Indian Vogue is mostly devoted to Bollywood, for example.)

Obviously, none of this refutes Matt’s argument about manga. And Japan (as my significant other pointed out) is something of a mecca for magazines; there are far more per capita than there are in the U.S., and the vast majority of them feature Japanese models. Maybe Vogue just uses Western models because it has overseas connections, and it helps it stand out on the shelves? Still, it’s hard not to conclude that there’s some suggestion here that the Japanese are taking beauty standards and beauty cues from Western models. It seems, anyway, a little more thoroughgoing than the Western fetishization of Asian women, which definitely exists, but probably wouldn’t be indulged quite so exclusively in an entire mainstream publication.

I don’t know. Anybody have other thoughts? Like maybe Bill, or somebody else who, unlike me, actually knows something about Japan?

Update: Pallas in comments points me to this fascinating link by W. David Marx about Japanese fashion magazines. Here’s part of what he says:

High-end fashion magazines, on the other hand, mostly feature clothing from European houses and luxury brands, pegging the center of legitimacy in the West. In order to ensure that the presentation harks back to the larger Eurocentric fashion world, magazines like Spur or Ginza — almost without exception — use non-Japanese and mostly Caucasian models. This prevents Japanese female readers from self-association, but that’s the point. Like the old Groucho Marx quote, “I don’t care to belong to any club that will have me as a member,” Japanese high-fashion fans do not want to see the clothes they desire on real-life Japanese people. There may be a tad bit of self-effacement in this sentiment, but it generally questions more elite Japanese consumers’ feelings about their own locale. The fantasy, therefore, requires a staff of non-Japanese models.

ViVi and Glamorous‘ overwhelming use of half-Japanese and three-quarters-Japanese models like Fujii Rina, Hasegawa Jun, and Iwahori Seri begs a more pointed question: what does race mean when it’s not a pure reflection of either here nor there? These magazines are not targeting some massive half-Japanese readership, nor do these models look foreign enough to recenter the magazine atmosphere outside of Japan.

Herein lies lingering issues of perceived racial inferiority. I’ve been told numerous times in Japan that “clothes look better on foreigners,” by which they mean “white or black people.” This is not objectively true (nor subjectively true, in my view), but editors have long used half-Japanese models on this principle to bridge the gap between Japanese self-association and cool “foreign” fashion. A half-Japanese model looks “foreign” enough to enhance the image of the clothing, but close enough to the reader to send a message of commonality. Things are changing, however. Male fashion magazine Popeye previously used only half-Japanese models but moved to more foreigners once readers voiced less need for racial similarity in considering the clothing.

So that would be at least a qualified vote for some level of “lingering issues of racial inferiority.” Though, again, that doesn’t mean that such lingering issues are reflected in manga iconography, necessarily.

Update 2: I just wanted to point out as well: Matt says that Japan “never has been a European dominated society.” That’s not true, if Europe includes America. Post-war Japan was absolutely American dominated. It was occupied; it’s government was restructured; cultural changes were handed down by fiat; etc. etc. Admittedly, that all took a relatively brief amount of time compared to the experience of a long-time colonial possession like, say, India. Still, it was pretty important, and had long-term consequences, both structural and, I would assume, psychological. To say that Japan was never under Western domination is not a supportable statement, I don’t think.

Update: And I’ve got a follow up post here