Hating comics is a strage business for me. I’m not against it – I’m not a Team Comics guy, worried about hurting Brian Bendis’ feelings. I’m a big Comics of the Weak fan, and I’m writing for the Hooded Utilitarian. I’m down with hate. But I find it unexpectedly difficult to hate comics.

Most comics, even some corporate ones, are the product of one or two idiosyncratic minds putting pen directly to paper. Even if I don’t particularly care for them, they tend to fascinate me as art objects. And the truly focus-grouped editorially-driven corporate comics? I’m frankly not invested enough in most of them to care if they’re all that bad. A bad comic of that sort is far more likely to inspire mere apathy. It takes something more than poor quality to drive me to hate.

To hate a work of art, I have to feel trapped or confronted by it in some way. Popularity will do it, sometimes. I almost wrote this essay about 100 Bullets, and then almost again about The Walking Dead. Neither of those books are the worst things I’ve ever read, but I also don’t find much to value in them, and their various levels of critical and commercial success serve to turn my general distinterest into a sneer of disgust. (You might think that sounds petty, and at one point I would have agreed with you. But I’m more inclined these days to see the general public reaction to a work as a legitimate part of that work’s existence, and worth reacting to in its own right. Plus, frankly, it’s just sickening to hear constant praise of work you consider undeserving.)

But most comics aren’t really that popular or that talked about. And unlike a movie, for which you sit passively in a dark room for a predetermined amount of time with nothing to focus on but Bradley Cooper’s “punch me” face, reading a comic at all requires active participation. If I’m not enjoying a comic, my energy for that participation just slides away, and I toss the book aside. I’m not trapped in it.

I can’t even fall back on old, reliable superhero nerd rage. Up until embarrassingly recently, I could become greatly offended by terrible superhero comics that violated my vague platonic ideal of what a superhero comic should be. A few years ago, I might have found it in me to write this entire essay on Identity Crisis, or a Mark Millar comic. But now, I try, but it fizzles. Superhero comics were never the most relevant things to begin with, and for me they’ve now spiralled off into utter inconsequence. (Superhero movies, on the other hand, are a constant presence in the cultural conversation, as well as being formally dominating experiences, and I have little to no problem hating THOSE. I hate that new Batman movie and I haven’t even seen it yet.)

So to write about a comic that I truly hate, I have to pick one that affected me on a personal level. I’ve picked a comic that, although it isn’t particularly important, let me down tremendously, and that I came to hate through sheer disappointment. That comic is Matt Wagner’s Batman/Grendel II.

I wonder for how many people Matt Wagner’s name still resonates. Briefly glancing over a chronology of his work, most of his output over the last decade-and-a-half seems to be scattered projects from DC or Dynamite, mostly writing franchised characters like Zorro or Madame Xanadu; some short work writing his own characters, some work drawing Batman. But nothing much to suggest that, for a time in the late eighties and early nineties, Wagner was one of the most consistently interesting and experimental of mainstream-minded American cartoonists. His was a mixture of complex but balanced geometric page layouts, high fashion and art deco-influenced design, a deliciously cartoonish line embellished with painterly colors, all mixed with a strong, semi-modernist writing style.

His earliest major work, Mage, a traditional fantasy quest recast to then-current ’80s urban America and strained through a cheeseclotch of comic book iconography, was the kind of thrilling learn-on-the-job opus that only a young cartoonist can deliver – from page to page and chapter to chapter you can see Wagner gaining confidence and competence in equal measure, his skill rapidly catching up to his ambition. In the middle of Mage, Wagner began his other major early work, Grendel: Devil by the Deed, a re-make of his first comics series, a crude but vibrant entry into the ’80s black-and-white boom called Grendel, about a young, wealthy sociopath named Hunter Rose who becomes the world’s greatest criminal mastermind out of want for a challenge. Foregoing the previous work’s lightly-manga-influenced adventure comics style, and having substantially improved as a draughstman, Wagner re-told (and expanded) the entire Grendel story in a series of tableaus and captions, the panels of the comics page divided up to somewhat resemble the composition of a stained-glass window. It was an experiment that earned high praise from then-fresh superstar Alan Moore in his introduction to the collected edition, and arriving as it did simultaneously with the virtuoso final issues of Mage, together they announced Wagner as most definitely someone to watch.

Wagner’s career post-arrival followed what now seems like something of a familiar path for eye-catching independent artists working in a mainstream idiom. He only occasionally drew his own characters again in comics form, instead making the likely economically expedient (as well as, admittedly, often aesthetically interesting) choice of writing a long run of Grendel stories for other artists to interpret, and plying his drawing skills on various franchise characters (including a Terminator comic that was actually fairly excellent, if memory serves) and many, many cover art jobs. Through the ’90s he did draw several short Grendel stories (the character of Grendel long-since transformed into a sort of freefloating symbol of the evils of mankind, with many different characters through time and space taking on the persona of the devil), and delivered a long-awaited sequel to his Mage series. The latter, though, is best discussed through the prism of the twin projects that are my true, belated subject today: 1993’s Batman/Grendel and 1996’s Batman/Grendel II, or rather, the aesthetic distance between these two works, both written and drawn by Wagner himself.

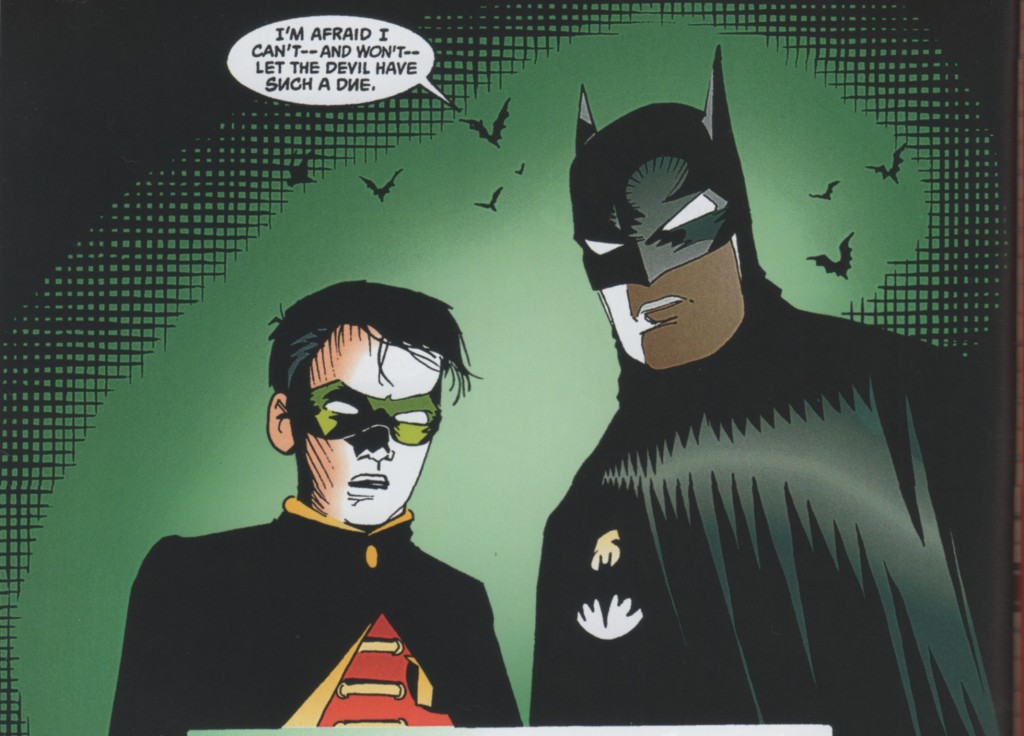

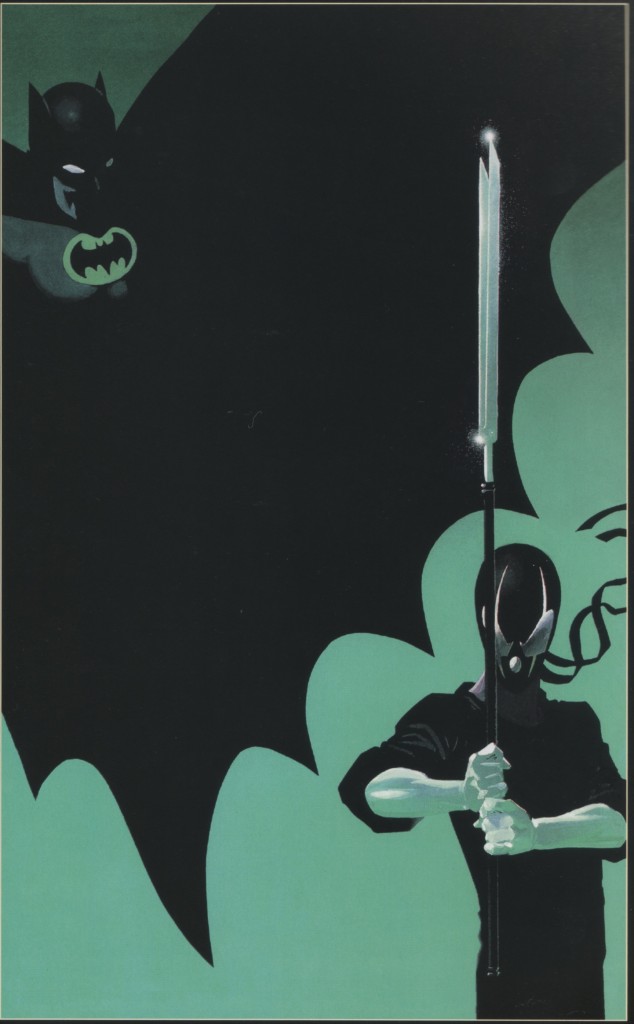

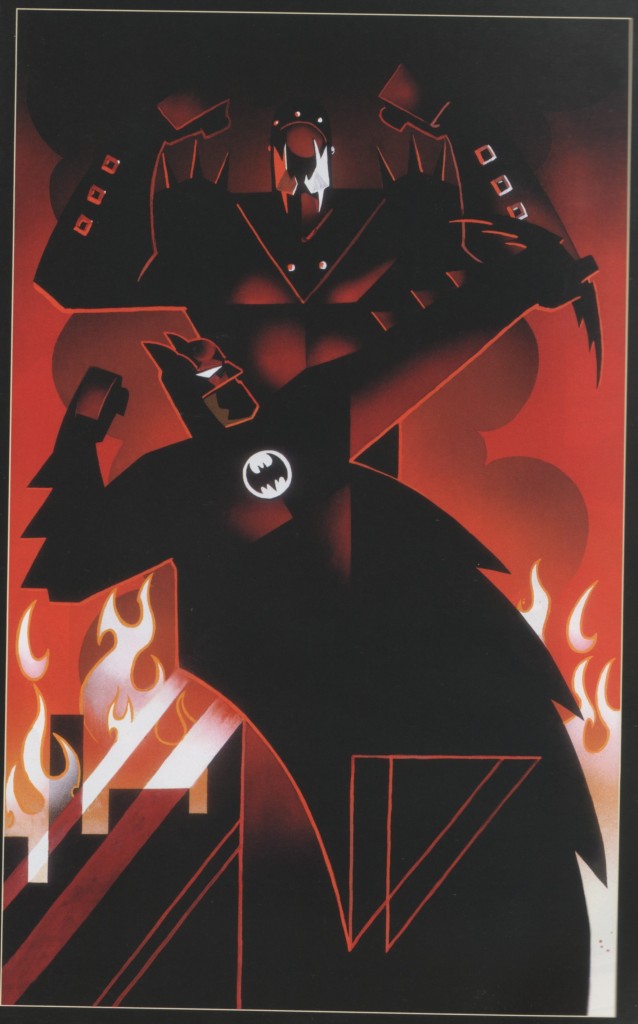

The Aesthetic Distance. (Left, Batman/Grendel. Right, Batman/Grendel II.)

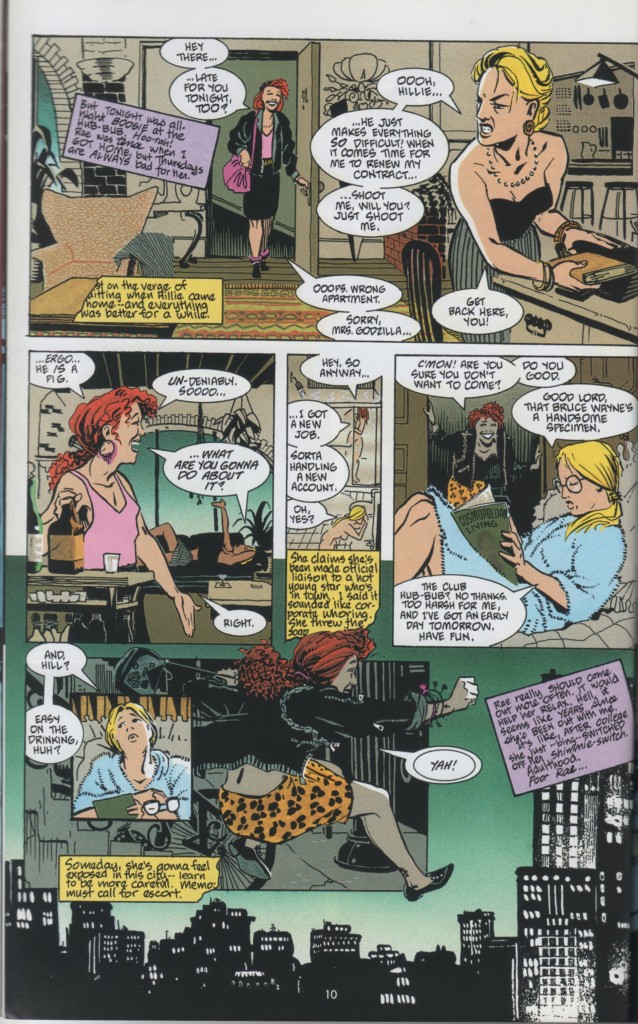

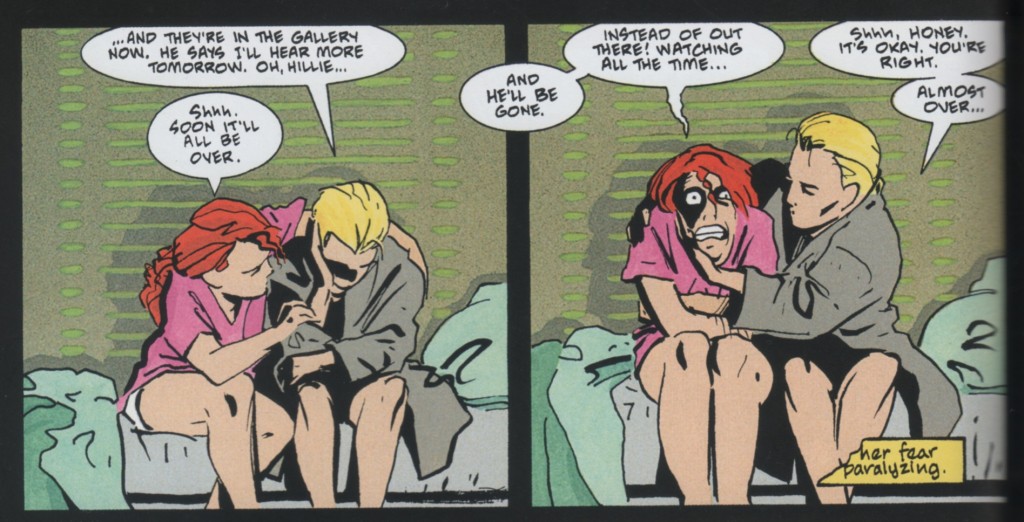

Batman/Grendel is far from the best comic ever made, but it does happen to be one of my personal favorites. Wagner, operating at his most formally innovative — with page layouts to die for, and the most elegant linework of his career (not to mention beautiful coloring by Joe Matt) — delivers a comic that on the surface purports to be about an epic battle between two wealthy playboys who enjoy violence on rooftops while wearing masks, Wagner’s own perverted inverse of Bruce Wayne versus the genuine article. The heart of the comic is actually, however, the story of two women, Hillary Ferrington and Rachel King.

The narrative consistently paints both Grendel and Batman as obsessive, destructive, meticulous, and both more than a little inhuman, both callous to the emotional realities of human life, the only difference being that one is callous out of sadism and the other out of expediency. And in the vein of the best of Will Eisner’s work on The Spirit, their entire superheroic clash of wills is constructed largely as backdrop to the story of Hillie and Rachel’s friendship, their tortured pasts, and their struggles against an increasingly hostile world filled with terrors such as wealthy playboys who enjoy violence on rooftops while wearing masks.

Wagner still fulfills the genre demands of a Batman story – there’s plenty of Batman puzzling things out at a computer, or thinking terse caption thoughts about how the weights in his cape are perfectly suited for urban combat – but he structures the big emotional beats of the story all around Hillie and Rachel. It’s a comic that uses the superhero setting to tell a human story, and unlike 99 percent of the stories that try that trick, it unembarrasingly succeeds.

Again, it’s still a Batman comic, still an inter-company superhero crossover, and still indebted to genre and melodrama in ways that could be argued to work to its detriment as a piece of art for the ages. It isn’t the best comic ever made. But I think that its formal mastery, compelling story, and welcome attention to gender politics and genre critique make it something kind of special. I love it a lot.

Batman/Grendel II, released three years later, takes a huge shit on everything that made Batman/Grendel even a little bit special.

The sequel finds Wagner in a different mode of storytelling. Gone are the tightly constructed and narratively functional layouts. In their place are splash pages crowded with unmoored smaller panels that often lead your eye in the wrong direction, to no good aesthetic effect. The most functional visual device is a re-hash of Frank Miller’s already decade-old television narration from The Dark Knight Returns. Gone, too, is the elegant linework. In 1996, Wagner had begun to loosen up his art, freeing himself from his devotion to the angles and fashions of 1980s illustration. The result is art that may very well have been more fun and personally fulfilling for Wagner to draw, but which looks clumsy and ugly on the page when compared to his previous style.

Most importantly, gone is any thematic or narrative resemblance to what made Batman/Grendel a minor miracle. This is not a story about any kind of human experience. This is a story about Batman fighting a cyborg from the future. Overwrought captions describe in agonizing detail how each of them feel about every moment of the story, endless verbiage that unironically calls Batman “The Dark Knight” and Grendel “The Devil” as it painstakingly narrates their utterly pointless and generally uninteresting fight to a stalemate that Wagner pompously postures as enigmatic and ambiguous in a desperate attempt for any kind of meaningful resonance.

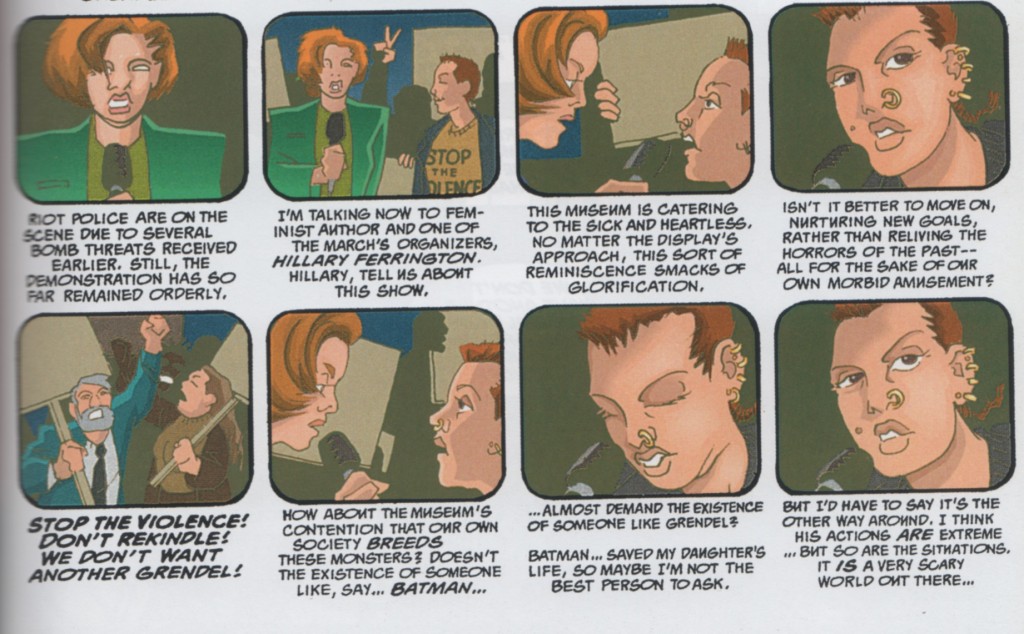

Batman/Grendel II‘s thorough betrayal of everything Batman/Grendel did right can be summed up by its very first page, in which Hillary Ferrington, the narrative and emotional heart of the former work, makes a cameo appearance that is used for exactly three purposes: (1) to display via her close-shaved head and multiple piercings that Wagner has ditched the elegant art deco stylings of old, (2) to lay exposition regarding the book’s fatuous internal free speech debate, and (3) to talk about how awesome Batman is. That Wagner is seemingly fine with disrespecting one of his best characters in this way speaks to the loss of something in him. And it is a loss that can be seen in his work through to the present.

After Batman/Grendel II, Wagner delivered his aforementioned Mage sequel, which displayed a similarly loose pencil and disinterest in the formal rigors of his previous work. It also, like Batman/Grendel II, displayed a much less nuanced sense of irony in regards to its straight-ahead mythic-adventure story. Where once Wagner used fantasy tropes to explore human situations, now the tropes themselves had become the focus. The same can be said of his post-’96 corporate superhero work (which makes up the bulk of his post-’96 work, in toto), at least that which I’ve read. Even the latter-day Grendel stories that he still occasionally writes for other artists are laden down with all the self-importance and forced darkness of a goth teen. Where once he used genre trappings as a delivery system for something bigger, he seems dedicated now to wallowing in those trappings for their own sake.

There’s a large degree of unfairness to what I’m saying. A perfectly valid view of all of this would be that I’ve merely gotten older, and my tastes have changed, while Wagner too has matured, and his art has shifted gears, just in a different direction. In some ways, his looser artwork may speak to Wagner achieving a more direct and free form of expression on the page. That I’m frustrated at the lack of particular thematic or formal tics in his current work is perhaps as much to do with my own nostalgia as any artistic lack on Wagner’s part. And like I said up top, Batman/Grendel II isn’t the worst comic in the world. If what you want is Batman fighting a murderous cyborg from the future, it might even be a pretty good one. But I can’t tell. I’m too sad at the loss of a cartooning voice I cherished, and too angry at the imposter that strolled in and tried to take his place. It’s an irrational feeling, but then again, so is hate.

__________

Click here for the Anniversary Index of Hate.