This essay first appeared on CiCo3. It was inspired by Nijla Mu’Min’s extraordinary film Deluge. Thanks to Amrah Salomon for feedback on the draft.

___________

Superheroes have celebrated origin stories. Gamma radiation gives rise to shapeshifting rage monsters. Extraterrestrial parentage provides biological powers. A magician’s curse or a nibble from a radioactive arachnid can turn one superpowered. The story of how one gets one’s powers is a defining part of superhero stories. It is, after all, the sine qua non of any superhero’s existence. But what about the universes in which the superheroes operate? Why don’t we look at their origin stories? And what can those origin stories tell us about the comics universes and popular discourse? What follows explores the origin stories of the DC and Marvel universes through their respective Atlantean populations, focusing on a missing narrative fundamental to the world in which virtually all stories in the DC and Marvel lines happen: African Slavery.

The Marvel and DC universes take place, with some exceptions, in the United States settler colony. The United States has two systemic structures without which it does not exist: African Slavery and Indian Removal (or at least it does not exist in anything remotely resembling its current form). These are the bedrocks of settler colonialism on the continent. The simultaneous destruction of the native world and construction of the anti-Black one define everything— from many colloquialisms in White American English, to property and land law, to policing, to the names of sports teams, to holidays. They comprise the preponderance of U.S. history, not to mention the country’s entire physical geography.

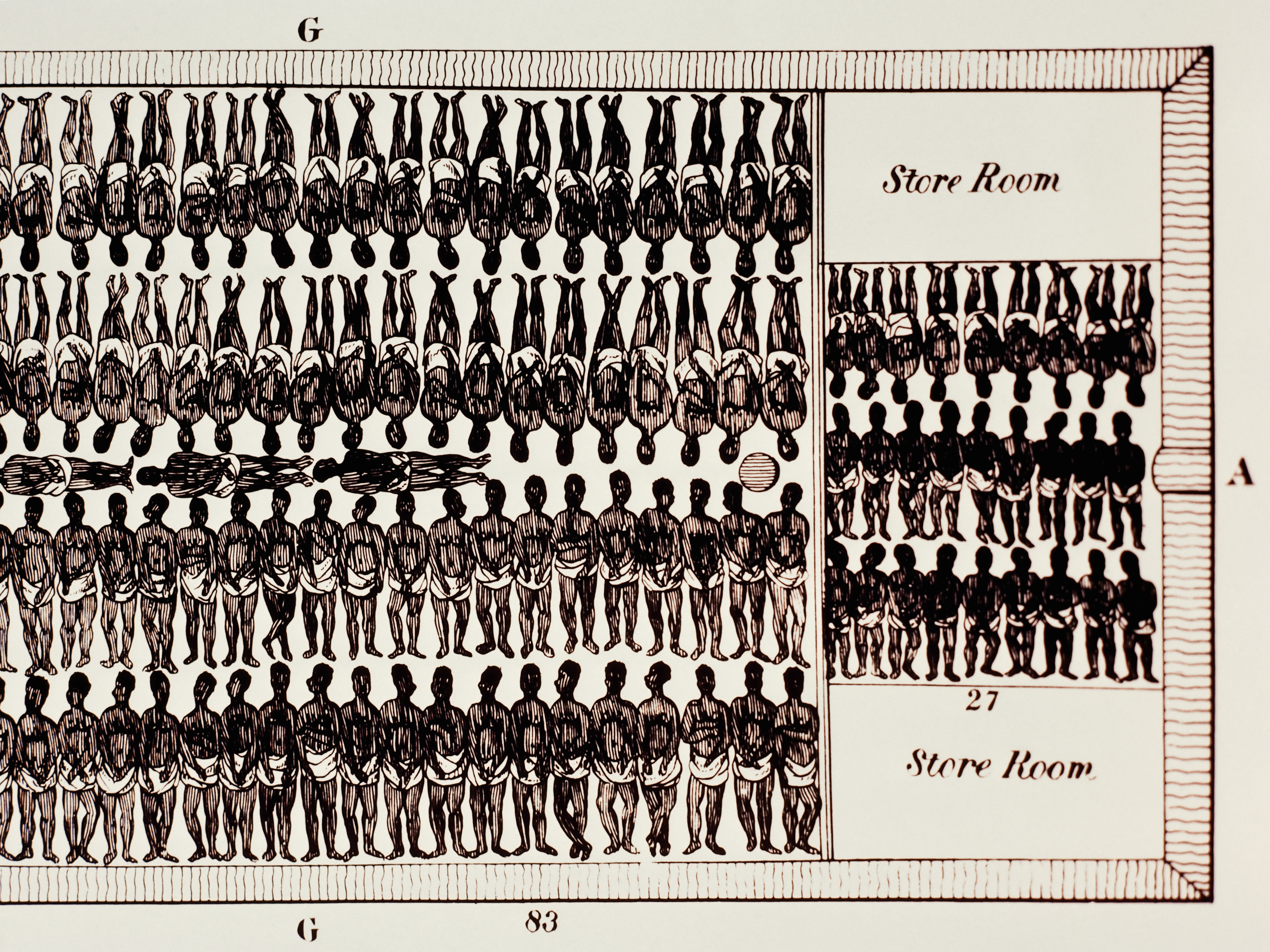

Can this be less true in the Marvel and DC universes? They both have Black characters, albeit relatively few and poorly drawn – often in both senses of the term. Black as an identity (or, per anti-Blackness, a site of capital accumulation and location for gratuitous violence) is tied to the legacy of settler colonialism’s African Slavery. If there was African Slavery then there was transport of enslaved peoples from Africa to colonized Turtle Island (North America). So where were the Atlanteans of the respective DC and Marvel universes during the Middle Passage? Where were Aquaman’s and Namor’s ancestors when the first rebelling or newborn enslaved Africans were tossed overboard to drown, be eaten by sharks, or drift slowly to the bottom of the Atlantic?

Exploring these ideas identifies dramatic narrative gaps in between the worlds where these stories purport to take place and the world in which they are told. That they are missing from the Marvel and DC universes exemplifies settler normativity, how the destruction of the native world and construction of the settlers’ anti-Black one is naturalized in and baselines politics and society. Settler colonialism is the organization of power that accomplishes this simultaneous destruction/construction. It is how native Turtle Island becomes the anti-Black North America for example.

It also creates a worldview for its inhabitants. In the same way that men struggle to see sexism, instead just seeing ‘normal’, settlers struggle to see settler colonialism. This settler normativity is one of our very frames of reference. It is basic to our understanding of the world. It is why when we hear about the 49ers we think about the football team or the miners of the gold rush, not the populist genocide the actual ‘fortyniners carried out, even though the depopulation of native California by far being their most enduring and impactful legacy. To question settler colonialism is to question the very world the settlers make. We don’t ask where Aquaman’s ancestors were during the Middle Passage because African Slavery is naturalized in society. It, like men not seeing sexism, is a level below the observable because it is the frame through which observations are made.

So where were Aquaman and Namor’s great-great-great grandparents when they first encountered African Slavery? What was their reaction? How would those reactions change the DC and Marvel universes? I explore some potential scenarios in the paragraphs that follow. Some of these fit inside the current DC and Marvel continuities, namely, the more horrible ones. Others disrupt the current continuities, including those that stop African Slavery in its infancy.

Scenario 1: Hotlantis

Those thrown overboard are rescued by Atlanteans and form an Afro-descendent Atlantean population or are assisted in returning home. This does not require significant adjustment of current continuities.

Scenario 2: Successful Anti-Slavery Intervention

The Atlanteans intervene against the slavers and prevent the Middle Passage from happening. Scenario five can work in conjunction with this. This is, in the DC universe term, an Elseworld and is irreconcilable with the current continuities. Scenarios 3 and 4 show why it is irreconcilable.

Scenario 3: Post-Intervention A

Superman’s rocket lands in Pawnee country since there is no Kansas in which to crash without African Slavery. Superman is now a Pawnee hero. This is irreconcilable with the current continuities.

Scenario 4: Post-Intervention B

Without African Slavery there is no such place as Gotham in which Thomas and Martha Wayne are shot to later be patrolled by their son Batman. They remain British aristocrats. If Bruce Wayne grows up to be a billionaire vigilante he does so in the UK. This is irreconcilable with the current continuities.

Scenario 5: No Response

The Atlanteans first encounter African Slavery through the at sea disposal of newborns or rebelling Africans and either react only to the drowned bodies and not to the act of drowning or simply go about their business. Here the Atlanteans would be concerned with whaling ships more than slave ships (though the ecological damage of African Slavery is in fact substantial!), to the degree they’re concerned with surface dwellers at all. This does not require adjustment of continuities.

Scenario 6: Unsuccessful Intervention

The Atlanteans attempt to intervene and fail and the Middle Passage continues. This is the basis for the Atlantean distance from the surface dweller world for the next four hundred years until the eras of Aquaman and Namor. This does not require significant adjustment of continuities.

Scenario 7: Complicity

Both Atlantean worlds are monarchies of one kind or another which suggests regressive politics. It is thus entirely feasible that Aquaman and Namor’s ancestors were complicit in the Middle Passage in some way. Was a tribute or toll paid to those who control the seas? Thus Atlanteans owe reparations of some kind and direct action at the Justice League headquarters is in order. This does not require significant adjustment of continuities.

Scenario 8: Opportunistic/Humanitarian Intervention

The history of humanitarian intervention is dominated by the interveners integrating a crisis or oppressive system into their own politics rather than ending the crisis or oppression. Alternately put, humanitarian intervention is with few exceptions a tool of empire. Entirely plausible in an intervention scenario is Atlanteans taking over the slave trade rather ending it. This does not require significant adjustment of current continuities.

___________

An honest account of U.S. history means dealing with the ugly truths of settler colonialism. Settler society cultural production helps avoid these ugly truths by producing myths. Not myths as in, superpowered beings in symbolic grand battles. But myths as in, the United States settler colony somehow being post-colonial. As it stands, the most implausible thing about comics is not that some beings can fly without apparent means of propulsion, but that they take place in a United States without Indian Removal and African Slavery. DC and Marvel comics are not imagining a utopia without colonialism even if they may think they are. Instead they imagine a world where colonialism doesn’t matter or doesn’t matter anymore, mountains of facts to the contrary be damned.

Comics can do better. Comics can narrate the colonial present and retcon their respective universes to where settler colonialism, including African Slavery and Indian Removal, happen and impact the universes accordingly. Elseworlds-style stories are one way of accomplishing this. For example there is the as-yet not made story Superman: Alien where the Man of Steel’s rocket is found by Mexican migrant workers on a Kansas farm. He then gets deported with his adoptive parents and grows up to be a Mexican superhero. That is at least as plausible as him being found by the white farm owners. This and the more tragic alternate visions offered above veer away from the current continuities in that they contextualize events as if they take place in the universes they purport to.

The question is one of decolonizing comics. Not as in, comics were colonized and must now be decolonized. That is silly. Nobody colonized comics books. To the contrary, comics in the United States are part of settler colonial cultural production. So in decolonizing comics we seek comics that are decolonizing acts; that are decolonizing narratives and, potentially, tools. Some indie comics and zines already explore this. Yet mainstream comics can too play a role in subverting settler normativity through dealing with the world settler colonialism made, the world in which the comics universes exist. One possible story to tell in this direction is the one that tells the story of the Atlanteans during the Middle Passage. Aquaman’s ancestors have some explaining to do.