So I’ve spent most of January and February plagued with some kind of….plague. It’s horrible, but it does mean I get to catch up on all the TV I’ve missed in the past couple decades. I blew through New Tricks earlier, then I watched Murder in Suburbia (not bad, really, and I liked Ash, though I usually guessed who dunnit in the first ten minutes) and then, for reasons known only to itself, Netflix suggested I might like a garden gnome musical and I had to have a soothing lie down*.

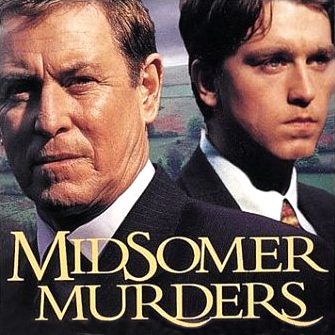

When I came back, I was armed with another friend’s suggestion: Midsomer Murders. Supposed to be the best acting evah. Which actually it really kind of is. John Nettles, who plays the lead detective, can do more with his eyebrow than most actors can do when chewing the scenery and screaming.

The basic premise of the show is this: DCI Tom Barnaby is a police detective in Midsomer, a pretend county in England that’s filled with picturesque but extremely violent villages. Barnaby always has a sergeant or factotum. In the early series, it’s Sergeant Troy, a handsome young man with even fewer brains than Barnaby. I quite like Troy, even if he is rather homophobic and kind of a jerk at times, he’s very kind and has a good heart. Troy eventually grows up to be his own detective and after five or so years, we get another sergeant, Dan Scott, who is a city-slicker lower-class modern-thinking twatwaffle. Er. Not that I dislike him or anything. Fortunately, Scott is eventually replaced by a much nicer, quite brilliant extremely kind, canny, and earnest Ben Jones, who started as a beat cop and got drafted by Barnaby.

So a crime will happen and then Barnaby will show up with his assistant and begin detecting. In between detecting (and sometimes during), we’ll occasionally get glimpses of Barnaby’s wife, Joyce, and adult daughter, Cully. Joyce is a gourmand who can’t cook and has a passionate love of acting and art. She’s got a kind heart and often is volunteering in various causes to save the world. Cully is an actress, but she has a bit more of her dad’s practical streak.

The charm of this show is in the setting and characters, the absurd cottage cozy murder plots, and in the fine wordplay. This is not a show to watch if you’re looking for realism in your motivations and villainy. It’s not about that. It’s also not about accurate police procedures–during most shows, Barnaby shows up to talk to important witnesses, who nearly always are:

- Conveniently called away on the phone, by a visitor or relative, or realize they’re late for an appointment. If I was the copper, I’d say, “Look, this is murder. You can be late to the annual orchid grower society meeting. Answer my questions fully or I’ll haul you to the nick.” Barnaby nearly always lets them go, and they’re often killed before their next appointment with him.

- Extremely shifty, to even the most oblivious eye. “What were you doing on Tuesday the thirteenth at 7 pm?” Suspect’s eyes dart around the room, “At home. Alone. Watching telly.” Does Barnaby ever ask what they were watching, to see if he can catch them in a lie? No, he does not.

- Basically barking mad. (Practically everyone on the show is.) “I couldn’t have been murdering anyone! I was preparing for the annual bell-ringing competition and nothing can get in the way of that!”

- Standing in their living rooms, in pub common rooms, or in the center of a church aisle, surrounded by other interested listeners. It’s not unusual for him to question several people, in a group, at the same time. “What were you doing on Tuesday the thirteenth at 7 pm?” he’ll ask the husband. “We were watching telly together. We had a quiet night in, didn’t we, dear?” says the wife. And her husband will nod. Even though the wife was out shagging the vicar and the husband was practicing skeet shooting. Or murdering someone. Only at the end of the show does Barnaby ever notice that this might not be the Best Interrogation Technique Evah. And since he asks the questions in public places, there’s always convenient eavesdroppers who can tattle to the village gossip or the local murderous fiend. Or who are the local murderous fiend.

It doesn’t do great things for Barnaby’s detecting, but it does up the body count, which is part of the fun.

Most of these shows have a pile of corpses at the end. A murderer will thwap someone to death with a shovel over a thousand year blood feud and then have to kill six other people to cover it up. Nobody’s ever a serial killer, although there are occasionally people who suffer fits of hereditary madness which drives them to various Foul Deeds.

So I’ve burbled on about how silly the detecting is, but let me give a glimpse of the charm of the show (because honestly, it does have plenty of charm!).

So as not to spoil lots and lots of episodes, we’ll start with the pilot, which should give everyone a decent feel of the show. It begins with two aged spinsters who compete to see who can find a Super Special Sekrit Orchid (I told you-flowers are dangerous!) in the local woods. Whichever one of them discovers the orchid proves it by marking it with a stake and then taking a photograph. Spinster One, whose name I have already forgotten, bicycles out to the woods with her basket and camera and special stakes. While out there, she finds the orchid, and while photographing it, discovers something shocking.

She races home, slams the door, makes two short phonecalls, and then dies. Suspiciously. Her friend and neighbor, Spinster Two, tells DCI Barnaby that it couldn’t have been an accident and that it was murder. Dun, dun, dun.

So Barnaby heads off to investigate.

There’s a local landowner who’s marrying his ward, a batty sister-in-law, the ward’s troubled artist brother, and the undertaker and his mother. The undertaker is My Very Favorite. He dresses like a Victorian gentleman, right down to a coat with tails and a little black ribbon in his hair, and he serves deeply troubling tea cakes on a very fancy cart. He’s gay as a spring morning and he and his mother have been blackmailing the entire village.

Of course, this eventually gets them brutally slaughtered, but since they show up looking exactly the same in another village ten seasons later, I’ve decided that they were sneaky enough to fake their own deaths and escape. According to the show, it’s just that they’re cousins or something, but I know Deep In My Heart that they survive.

Ahem.

So anyway.

There’s quite a few different suspects. The sister-in-law of the local lord, who thinks she shot her own sister with a rifle during some kind of pidgeon slaughtering party. The local ineffectual country doctor whose wife is having an affair with the local lord’s estate manager (and he’s very pretty–I can see why she strayed). The straying wife, who is worried about being caught. The daughter of the doctor who is having a fling with the mad artist (who always wears a truly tragic pair of denim overalls and chews the scenery like he got a degree in emo artist.) The waif like ward. The waif like ward’s artist brother. And some other people, who I forget.

While Barnaby wanders around interviewing people, you get to see lots of gorgeous scenery and cottage gardens and English shooting parties and quiet country lanes. Barnaby does have a very thoughtful mien and a quiet way about him. I suspect that dogs would curl up happily at his feet–good stillness. Troy, the current sergeant, is like a young overexhuberant bull, brashing his way through undergrowth and making rash assumptions about whodunnit and generally being kind of a homophobic jerk.

Much of the mystery, as many of the mysteries in this show are, is concerned with who was having naughty fun times in the woods on a blanket with whom.

As soon as I’d figured out that this was the big mystery, I suggested to my mom that obviously it was the brother and sister, because the whole show had a Greek/Shakespearean tragedy feel to it, and what better tragedy than random incest?

And so it proved.

Barnaby eventually figures it all out by contacting the now-adult childrens’ nanny and things are revealed and the wedding gets called off and the two young lovers commit suicide in the wood via shotgun. You know, as people do.

There’s some clever clues, phone calls, obscure words, etc. in the grand tradition of cozies everywhere. I’ve lost track of the number of times people get shot to death with arrows in Midsomer county, but it’s a lot. There’s psychics and witchcraft, the second sight, new age weirdos, writers’ societies, art fraud, retellings of Hamlet, shoutouts to Dorothy Sayers, poisoning by mushroom, hemlock, and various other dodgy substances, as well as a couple of deaths via pitchfork. Not to mention those being driven to suicide, mistaken identities, Meaningful Messages With Flowers on corpses, and so on. There’s a great episode where the local theater troup puts on Amadeus and the plot of the play and the retelling of the mystery weave together–it includes a truly horrible guy committing accidental suicide via razor on stage during the dress rehearsal.

Tiny intense hobbies take up peoples’ worlds, as they do in real life, and those often form the basis of the plot. Villains are just as likely to kill over who was prouder of their rose bushes as they are to get an inheritance. Small town dances, choir rehearsal, bell ringing, book groups, local history library photo retrospectives, fly fishing, magic tricks, Masonic societies (including the silly aprons), and more.

If you’re tired of watching ultra-realistic grim urban crime about the destruction of society that reminds you too much of yesterday, give this a try. My favorite so far is probably the revenge plot where the villain stakes a guy in a croquet circle and then catapaults the oenophile to death with vintage wines using a small siege engine (Season 8, Episode 6).

These are currently streaming on Netflix or Amazon Prime.

* Someone here suggested I continue What The Hell Did I Just Watch into a regular feature. Maybe Netflix thought so, too. If you all feel the need for a garden gnome musical review, I’ll take it under advisement, but I may also need suitable bribes. Liquor. Brownies. Exotic drawing ink. A large wall against which to thwap my head until the images leave it. You know. The usual.