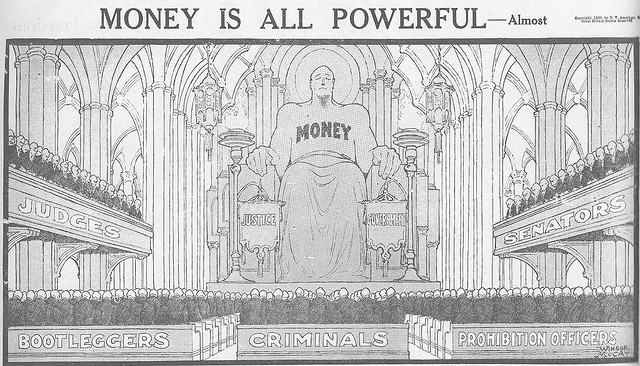

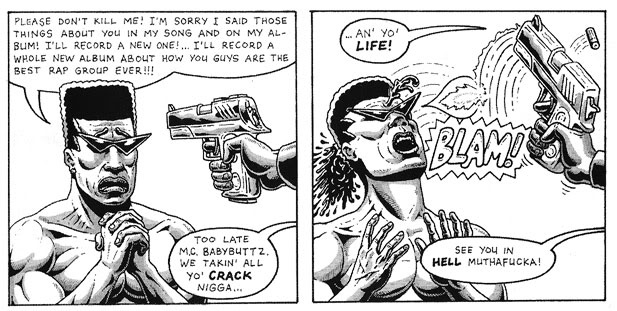

In a series of articles on race and superhero comics, several HU regulars cast doubt on the possibility of racially progressive superhero comics. This, in turn, prompted Noah and others to suggest that the superhero genre is itself racist. Conceived in an era of scientific racism and honed through nationalist propaganda, the superhero genre seems to contain a worldview that pulls creators toward narratives that are, if not exactly white supremacist, unable to comment thoughtfully on issues that concern African Americans.

Of course, there are rebuttals. Some argue that because two Jewish kids created the Ur-Superhero back when Jews weren’t exactly white, therefore superheroes can’t be totally racist. However, this rebuttal ignores the fact that you needn’t be racist to create racist art. Another rebuttal follows from the idea that the traits that make the superhero different also make them super, which suggests that superhero comics portray difference, and maybe even diversity, as a social good. This seems like a difficult possibility to reject out of hand, but the fact that few superhero comics have thoughtfully addressed issues of diversity creates a difficulty for anyone looking to make the case. To my mind, this suggests that the jury is still out on the question of whether the genre is racist.

But what does it mean to call a genre racist? To answer this question, I’ll start with a brief definition of genre.

Following the work of Carolyn Miller, I’m defining genre as social action, i.e., as a typified response to a recurring situation. Defined as such, we recognize eulogies as eulogies because they respond to a situation that recurs (the funeral). This is not to suggest that the genre is not defined in part by form and content, but that this form and content responds to, and is therefore shaped by the situation and audience to which it is addressed. As the funeral situation evolves and audiences for eulogies change, the genre will evolve with it. So, if you found a eulogy in an old file cabinet you could recognize it as a eulogy based on its formal characteristics. However, those formal characteristics exist as such because they address recurring needs and expectations.

If superhero comics are a genre, to what situation(s) were/are they addressed? Often, we look for the answer in eras. For example, we might argue that Superman reflects the anxieties of late depression—a culture of feeling shaped by a sense of injustice and the need for strong leadership. Not coincidentally, this was the era in which the US flirted with fascism, and in which certain European nations embraced it. Thus, we have the argument that the genre is tainted by fascism, or a fascist mindset that trips easily into racism. However, by defining an era according to a specific concern, one is forced to operate at a level of abstraction at odds with the rhetorical conception of a situation, which includes historical context, but also material constraints such as medium, power dynamics between the producers of and audiences for texts, and so on. Where does this leave us?

To define superhero comics as a social action, i.e., a motivated, conventionalized response based on the demands of a recurring situation, I think we need to look at the relationship between the producer and the audience. Specifically, we need to see comics as a response, at least in part, to the situation of adolescence as experienced by boys. After all, adolescent boys were, until quite recently, the primary audience for superhero comics. Moreover, and more to the question of race, white adolescent boys were the imagined audience for comics, which is to say they were the audience to which comic creators addressed their narratives.

Is it any surprise, then, that the X-Men are a lousy metaphor for race? Sure, mutants appear as a persecuted minority, but they’re a minority that assumes great power as a birthright. This strikes me as a better metaphor for the young white man who is old enough to see power on the horizon, but is feared and despised by the adult world during this particular stage of his development. Compare this to the young black man, who can expect to face fear and hostility for years to come.

A similar combination of power and persecution dogs Superman. Though he is celebrated as a hero, he submits to daily humiliations. Why? We can psychologize Kal-El all day, but I’d bet money that the answer lies not in his character but in the demand it fills. Namely, it’s an effort to connect with an audience of young men subject to the regular degradations of adolescent life.

How does race factor into all of this? After all, it’s not as though young black men aren’t subject to fear and persecution. The answer is that superhero comics, as a general rule, assume that unearned power lies behind or beyond the fear and the persecution. The mutant, the Kryptonian, the scion of billionaires, the kid genius who sticks to walls… All of these characters could get everything they want and more. Only two things hold them back. One is ethics, and this is a potential positive to the genre. The other is less positive: it’s the notion that lesser beings are holding them back (I’m looking at you, X-Men).

So, is the superhero genre racist? As a rhetorical theorist, I’m contractually obligated to answer yes, and no.

Yes, the genre is racist. It is addressed to a situation unique to an increasingly small but nevertheless over-privileged group. As a result, it developed conventional features that make a dog’s breakfast of any effort to incorporate issues of social justice that don’t entail being nicer to young white men.

No, the genre isn’t racist. Situations recur, but they evolve over time. As the audience for comics grows increasingly diverse, the conventional features of the form will change accordingly to better address the situation of the readership. Sure, we’re going to read some confused comics as we transition, but it will all work out in the end.

In short, the answer to the question of whether a genre can be racist is yes, but it doesn’t have to be. As to whether the superhero genre is inherently racist, I want to suggest that it has developed some narrative conventions that are, if not racist, seriously problematic. However, I’d be reluctant to consign the genre to the realm of minstrel shows and Orientalist travelogues. Instead, I’d argue that recent flare ups over its less progressive features indicate a genre that’s struggling to expand the range of situations to which it can speak.