Figure 1:Suicide Squad from the CW’s Arrow

The superhero has emerged as the trending symbol of our mediated world. Musings over Marvel’s and DC Comics’ relative successes adapting characters to the big and small screen opens the door to some interesting moments of cultural contemplation. As Peter Coogan suggests in a recent essay entitled, “The Hero Defines the Genre, the Genre Define the Hero,” the link between the superhero and the genre are not incidental.[1] The selfless nature of the superhero and its genre reflect pro-social values Americans feared threaten by a rising urban industrial order. Changing the superhero then, echoes wider fears of disruption stemming from the loss of tradition. In this framework, the superhero becomes a measure of communal stability in some minds. As the superhero evolves enough to maintain its relevance, these characters offer context for cherished values placed in a modern world. As these characters are recreated for film and television audiences, they provide a window on the pace and scope of our collective evolution.

Over the last two seasons, the CW’s Arrow has emerged as an effective vehicle for adapting DC Comics characters to a broad audience. Like the Marvel Cinematic Universe before it, the creative minds behind Arrow built their world by mixing decades of comic book adventure. Free to pick and choose, they adapted with an eye toward creating easy entry for new consumers and maintaining the loyalty of established fans. The recent appearance of Amanda “The Wall” Waller, on Arrow highlights the fact the current comic book culture is filled with questions linked to identity and gender. In deciding to adapt this character, the producers have entered into that dialogue. Taking their cue from the 2011 reboot called the New 52, Arrow’s Amanda Waller is a marker of larger identity concerns.

Figure 2: Suicide Squad #1 (2011)

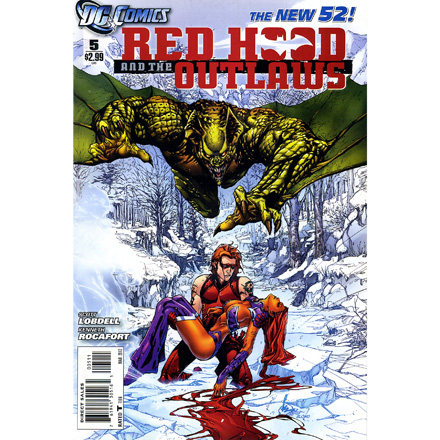

The New 52 restarted DC comic publications from the beginning. Complaints about this reboot have focused on missed opportunities. Critics point to uneven characterization, failed opportunity linked to diversity and the reorientation towards new (hopefully younger) readers by abandoning continuity. These complaints are understandable, but perhaps unfair. In 1985, the company revamped the publication line with its Crisis on Infinite Earths mini series. Often lauded by fans, it was greeted with complaints as well. History has proven that story a milestone. With this in mind, we may see “The New 52” lauded for the push toward genre variety and the integration of formerly sacrosanct characters from Vertigo, the publisher’s mature reader line, back into the mainstream comic universe. Whatever history’s judgment, the immediate media spotlight has and will likely continue to question the depiction of female characters.

Concerns about gender and representation in comics are not new. However, in the context of the 2011 reboot, the re-imagined overtly sexualized look and actions of female characters such as Starfire and Catwoman triggered protest. Adding to these concerns, products, drawn from comic book source material, reflect a dynamic of gender objectification long cited by critics. In particular, the outcry over the failure to produce a Wonder Woman film and criticism about Rocksteady Studios’ depiction of Harley Quinn and Catwoman in its Arkham game franchise has troubled fans.[2]

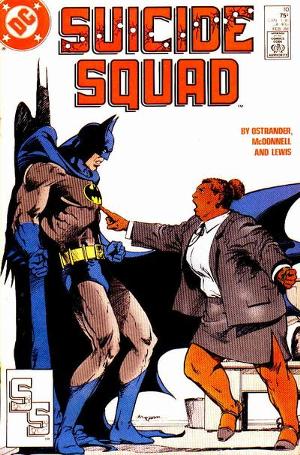

Arguably the transformation of Amanda Waller is a crucial part of this dialogue. Introduced in 1986, the comic book Amanda Waller is an African-American middle-aged woman with a heavy build working as a government bureaucrat. She is a unique example of a black female authority figure in mainstream superhero comics. Her serious demeanor and steely determination managing a government-sanctioned task force called the Suicide Squad made her a fan favorite. Effective and dedicated, Waller commands the respect of villains and heroes alike. Animated television and film appearances have further embellished Waller’s status among fandom.

Figure 3: Suicide Squad Vol. 1. #10 (1988)

In revamping the publication line, DC editors made decisions designed to make character more accessible to a broader (less expert) reading public. Clark Kent/Superman is no longer married to Lois Lane (quasi-damsel in distress). Instead, he is dating Wonder Woman/Diana Prince, creating the ultimate “power” couple (Couldn’t help myself). Abandoning the Superman /Lois Lane relationship highlighted an edict that marriage is prohibited in this new status quo. This stance was perhaps made more frustrating because it was only fully articulated in the midst of a public furor over the editor’s decision to derail the same-sex marriage of Batwoman (Kathy Kane), the publisher’s most prominent lesbian character. The tumult surrounding that decision and the continued concern over female character placement and representation prompts me to ask, “What about Amanda Waller?”

Waller transition in the New 52 has received comparably minor protest. Arguably, while heroes and villains deserve the main scrutiny on a comic page, Waller’s transformation has a greater impact because of her unique status as a woman of color in a position of authority. The lack of concern about Amanda Waller’s presentation highlights gender and race intersectionality.[3] Articulated by black feminist intellectuals such as Frances M. Beal and Alice Walker, the interlocking nature of gender and racial bias creates overlapping barriers linked to race and sexism for women of color.[4]

Arguably, Amanda Waller has been affected by gender and racial expectations since her introduction. The original characterization could be seen as leveraging the nineteenth century mammy stereotype to great effect. Waller was a sexless maternal figure who valued her superior’s goals, but showed disdain for the team that acted as her quasi-family. Unconscious and unspoken, Waller’s placement as a “strong” and “principled” bureaucrat loyally working for the government confirmed some assumptions. Yet, with depictions of African-American women in the 1970s caught between a normalizing figure such as Diahann Carroll’s single mother professional in Julia (1968-1973) and Blaxploitation inspired icons such as Pam Grier’s tough vigilante Coffey (1973) Waller’s debut in the 1980s struck a more balanced note in a social and political landscape shaped by warring conservative and liberal views of African-American life and culture.

Neither objectified nor objectionable, there has been a consistency to creator’s attachment to Waller as a supporting character. Always in the background, always working for the “greater” good, her experience compounds the critical assessment that minority characters in comics are only allowed to function within a limited assimilative framework. Now, younger and more traditionally beautiful, Waller does not have the same gravitas. Waller’s function remains the same, but her appearance now creates a radically different context to understand her. Like other female characters in the New 52, her physical beauty brings her more in line with male expectations, but in her case those expectations have an added layer of racial exoticism. Now seductive as well as powerful, the new Amanda Waller hovers between a “predatory” Jezebel and a “malicious” Sapphire stereotype. At once desirable (Jezebel) and cruel (Sapphire), the new Amanda Waller carries the full weight of gendered racial expectations in a manner that does little to differentiate and everything to limit her character. The fact that this Waller has made the jump to Arrow reinforces the transformation in the pop culture landscape. Still, Amanda Waller’s transformation is a marker of a conversation we are not having gender and diversity in comics.

[1] Robin S Rosenberg and Peter M. Coogan, What Is a Superhero? (Oxford University Press, 2013).

[2] It worth noting the recent Arkham Knight (http://www.ign.com/videos/2014/03/04/batman-arkham-knight-father-to-son-announcement-trailer) game trailer featured a redesigned Harley Quinn that is arguably less problematic.

[3] “Race/Gender/Class ‘Intersectionality’,” accessed March 16, 2014, http://www.uccnrs.ucsb.edu/intersectionality.

[4]Frances Beal, interview by Loretta Ross, video recording, March 18, 2005, Voices of Feminism Oral History Project, Sophia Smith Collection, tape 2.

Julian Chambliss is Associate Professor History at Rollins College and co-editor of Ages of Heroes, Eras of Men: Superheroes and the American Experience.