When aspiring to seek racial harmony through media, a little bit seems to go a long way. Instead of adding one black character to a film’s cast, add two. It does not matter that in Avengers: Age of Ultron, Anthony Mackie’s Falcon never interacts with Don Cheadle’s War Machine, as they’re both appearing in the same scene. Captain America: The Winter Soldier went the extra mile by having Mackie’s Falcon and Samuel L. Jackson’s Nick Fury exchange two scenes of dialogue. The fact that their characters’ personal investment centers on white Steve Rogers should not erase the fact that they are two black men interacting with each other, for however briefly.

But it can, and it does. Most narratives in film or television are willing to show some degree of racial representation, but generally speaking the central focus of said narratives tend to be on other things. This is where stereotypes bleed in, and the marker of authentic representation becomes blurred. Too often the black hero becomes a minstrel. As a result, POC tend to examine media closely for authenticity and veracity, often with a good degree of skepticism.

The quest for authenticity reaches great heights in the FX miniseries American Crime Story: The People vs. OJ Simpson. Based on the book “The Run of His Life: the People vs. OJ Simpson” by Jeffery Toobin, the series’ inherent attraction is that it retells one of the most famous murder trials in American history. American Crime Story: The People vs. OJ Simpson has thus far enjoyed critical success due in no small part to its near-slavish recreation and theatrical swelling of the facts and events of the case. The actors (headed up by a string of A-list talent including Courtney B. Vance as Johnnie Cochran and Sarah Paulson as Marcia Clark) have arrested viewers with their multidimensional and powerful performances.

The show’s fifth episode “The Race Card” focuses, as the title suggests, on the racial tensions that squeezed the OJ trial so firmly. Written by Joe Robert Cole and directed by John Singleton, much of the focus of racial anxiety centers on Prosecutor Chris Darden (played by Sterling K. Brown) and his nightmarish experiences in going up against the defense team led by Johnnie Cochran. The tone is set by an opening scene in which Cochran is harassed by police while driving his daughters to dinner (he lectures his children not to use the word “nigger” when asked if he was called that by the policeman).

Cole and Singleton’s script sympathizes with Darden, beginning with a press event for Cochran in which he argues that the inclusion of Darden (who is African-American) on the prosecution is a cynical example of tokenism. As the trial begins, Darden makes a case to the court that the use of racial epithets by LAPD officer Mark Furman should be deemed inadmissible so as to not inflame passions of the majorly black jury. Cochran, passionately, responds by accusing Darden of belittling the morality and emotional capacity of African Americans, reminding the court that they “live with offensive looks, offensive words, offensive treatment every day.” “Who are any of us to testify as an expert as to what words black people can or cannot handle?!” It’s a roundhouse blow to the prosecution, particularly to Darden as Cochran turns back to his seat and whispers to him “Nigga please”.

It is here that the episode turns from a recapitulation of a real life court drama into a trial of black identity. The court plans to tour OJ Simpson’s house, so Johnnie Cochran re-styles it as a more recognizably black home, replete with photos of black people and socially conscious artwork such as “The Problem We All Live With”, replacing Simpson’s Patrick Naegel collection and photos of his white golfing friends. Cochran tells OJ that the redecorating will get the mostly black jury on his side, and that it will help to frame the narrative of the trial as a case of police harassment against an innocent black man.

OJ responds “What’re you trying to say about me Johnnie?” before defending his lifestyle, arguing that he earned his wealth himself, and rejecting the idea that he could have done more for the black community. Those who wanted money or aid from him, he says, were just looking for a handout.

Darden’s character is sympathetic. From scenes in which he vents frustration to his parents to his vexation when he tries to explain to Marcia Clark how people downplay their racial bias by being polite, Sterling K. Brown makes the character thoroughly understandable. But Johnnie Cochran, while theatrical and tenacious, also generates inevitable suspicion. The episode presents Cochran telling the other lawyers that their job is to present a better story of what happened on the night of the murders than the prosecution. He also tells Chris Darden that he is in the trial to win – not be professional. Cochran says he believes in Simpson’s innocence, but he comes across as a ruthless individual who is utilizing race to meet his own vindictive ends.

You could perhaps say the same of the show’s producers. The series was developed by writing duo Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski, who co-produce the show along with Brad Falchuk, Nina Jacobson, Brad Simpson and Ryan Murphy. All of these creators are white. Though current national polls show that the majority of both white and black Americans believe Simpson probably killed his ex-wife Nicole Brown and Ron Goldman, there was a much sharper divide between the races twenty years ago.

The series does not demonize Simpson; it only presents evidence previously recorded or corroborated during the trial. But real-life overwhelming evidence employed by the show helps shape an argument for his guilt. Suddenly racial diversity becomes a tool for furthering a belief held disproportionately by white people who remember the Simpson trial. Thus, every detail and scene of sympathy and humanization of black people is used to advance a narrative congenial to white opinion.

And so one could argue that the use of people of color, and of real world people and events, becomes a sinister Trojan Horse, or at least it can. But must that be the case? Must white creators inevitably infect a work with prejudice? It’s a popular theory held in several arenas, particularly comic books.

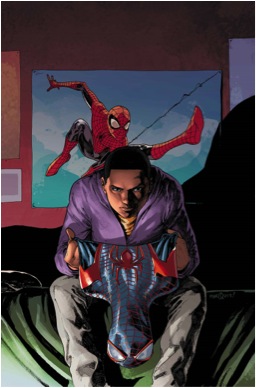

The March 2nd 2016 issue of Spider-Man, starring half-Black half-Hispanic Miles Morales, was met with controversy when writer Brian Michael Bendis had the character express negative emotions towards his ethnicity. In the issue, amateur footage from a fight involving a tattered clothed Spider-Man with his skin exposed results in an online blogger enthusiastically broadcasting that the new hero is a POC. Miles responds with feelings of discomfort and angst.

“I don’t want that.” Miles says.

“Want what?” his friend Ganke asks.

“The qualification.” Miles responds.

The scene has elicited a number of responses from various groups of people ranging from GamerGaters praising the book for its rejection of “SJW” agendas to reviewers criticizing the issue for its attack on female fans. Black Nerd Problems.com wrote that says that the scene “is classic white liberal rhetoric” which “paints a world in which there are no problems…it serves as a tool to maintain the status quo.”

Brian Michael Bendis took to Tumblr to address the negative reaction with a “Damned if you do, damned if you don’t” type of response.

“As I’ve said many times before I used to work at a major metropolitan newspaper and I learned there that anything you say about politics, religion, sex or race… No matter what you say… Half the people reading it will vehemently disagree. that’s just the way it is.

so some writers either decide they want or don’t want the conversation. sometimes it’s a conscious decision and sometimes it’s an unconscious decision.”

When I first read the scene, I immediately felt uneasy in recognizing that the words of a conflicted black kid were coming from the mind of a white writer. Whether or not the scene was written with any sort of liberality couldn’t escape those indicting facts. I took it upon myself to determine, with my own sense of blackness, if I felt this was or not authentic, and it was. It was not believable to me that a thirteen year old would have a fully rounded concept of his own racial identity juxtaposed with the cultural context of the modern world. Not to suggest that he would be completely unaware, but to me Miles Morales would not be as expressive with his blackness as John Stewart was in his first Green Lantern appearance.

The complexity is self-evident. Each POC will see different kinds of representation with each character, as such defines our individuality. It matters not than Bendis’ own children are African American, or that he created Miles Morales. There will always be that double consciousness that pervades every story and creeps into the minds of every POC.

So what is the solution? It would appear to be having more POC producing more of the consumer’s material. That’s not always a surefire way to make a coherent story, but it is a first step. Those are more valuable than failure because each step towards perfecting representation produces a normalizing effect. It also re-contextualizes missteps taken by white people as cautionary examples to learn from. Perhaps they were not so ruinous if evading their failures gets us to where we need to be. After all, Shaft was created by a white author. But not every black person in America likes Shaft.

No one person knows how to totally represent their minority status. Social constructs do not come with a “How-To” kit – the instructions manual only includes a lifetime of misunderstandings and imbalanced power structures, with varying degrees of oppression from person to person. Integration helps us deconstruct the construct. We need the successes and failures of others and our own internal vetting process to get to where we want to be.