Around the time I was writing my critique of Orientalism in Craig Thompson’s Habibi a strange thing happened: I got to know Craig Thompson. Through a mutual acquaintance and a series of chance convention run-ins at San Diego Comic Con and the Alternative Press Expo in San Francisco, we became casual acquaintances. While writing up my honest reaction to Habibi I decided to burden our new friendship with the weight of criticism by calling to ask him a few clarifying questions. The result expanded the scheduled ten minutes of chat time in to a much longer conversation about Orientalism, feminism, cultural appropriation, the burden of relationships, and the thematic successes of Habibi. The only thing I’d like to add before presenting our conversation is something that should become evident to you while reading it: Craig Thompson is a supreme class act. Not only did he take time out of an extraordinarily busy schedule to directly confront my criticism of a book he spent over seven years making, but he did it with an amount of grace and humility that I didn’t know was possible.

Nadim Damluji: I want to start by talking about Orientalism, which it appears you were conscious of during the process of making Habibi. During the creation process, did you ever second guess your ability the distinguish between using Orientalism as a playground versus simply reproducing it?

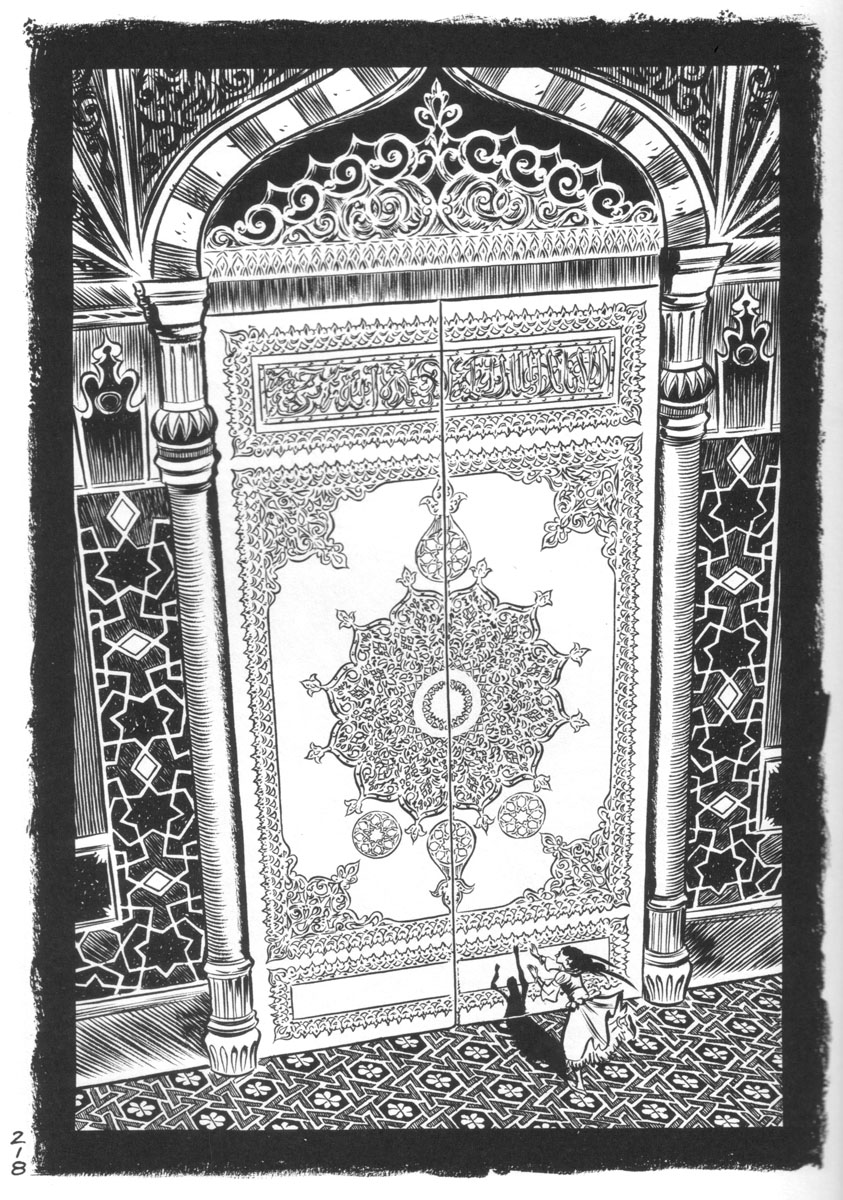

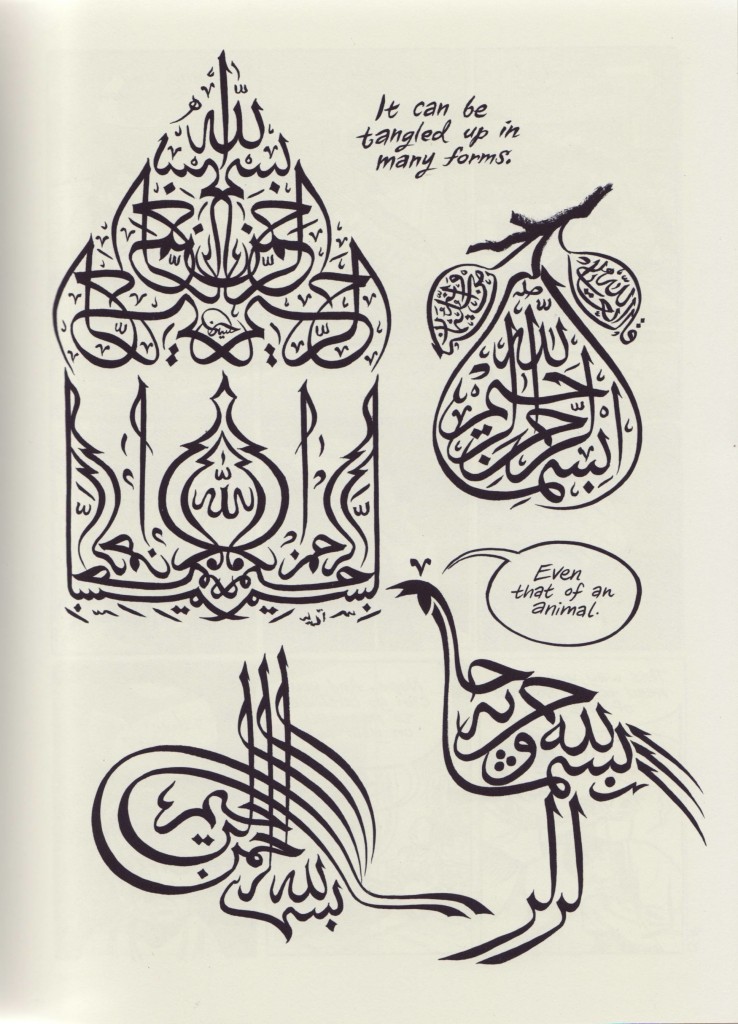

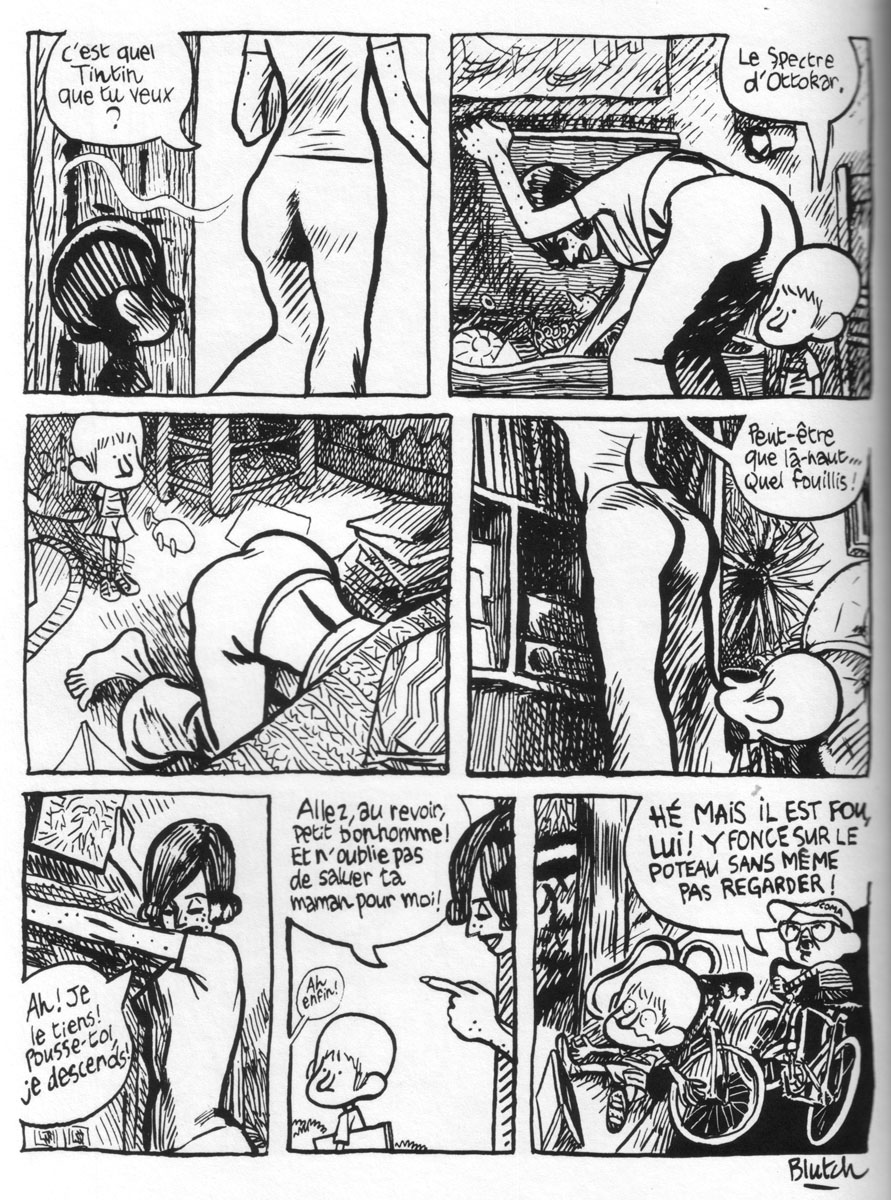

Craig Thompson: I don’t want to repeat myself, but I keep saying that the book was a conscious mash up between the sacred medium of holy books like the Qu’ran and the Bible and the trashy medium of Comic Books. And I was keeping in sight this sort of unpretentious, self-deprecating, low-brow, motivation of comics.

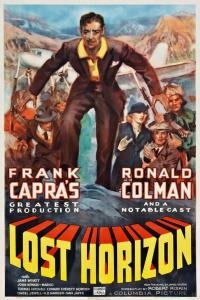

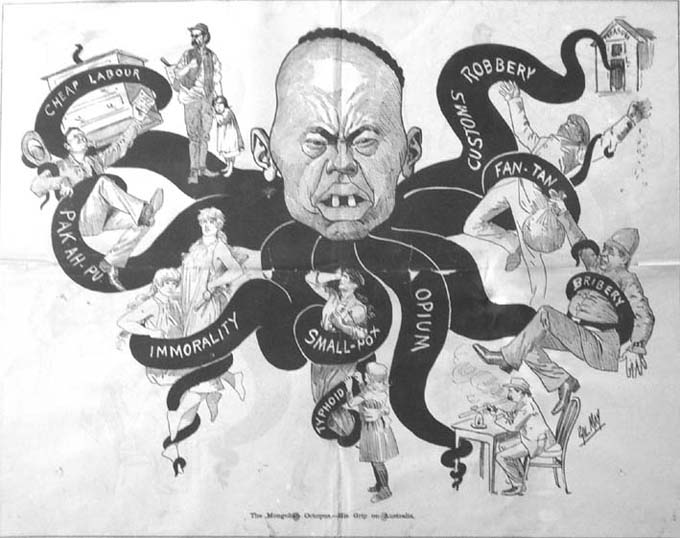

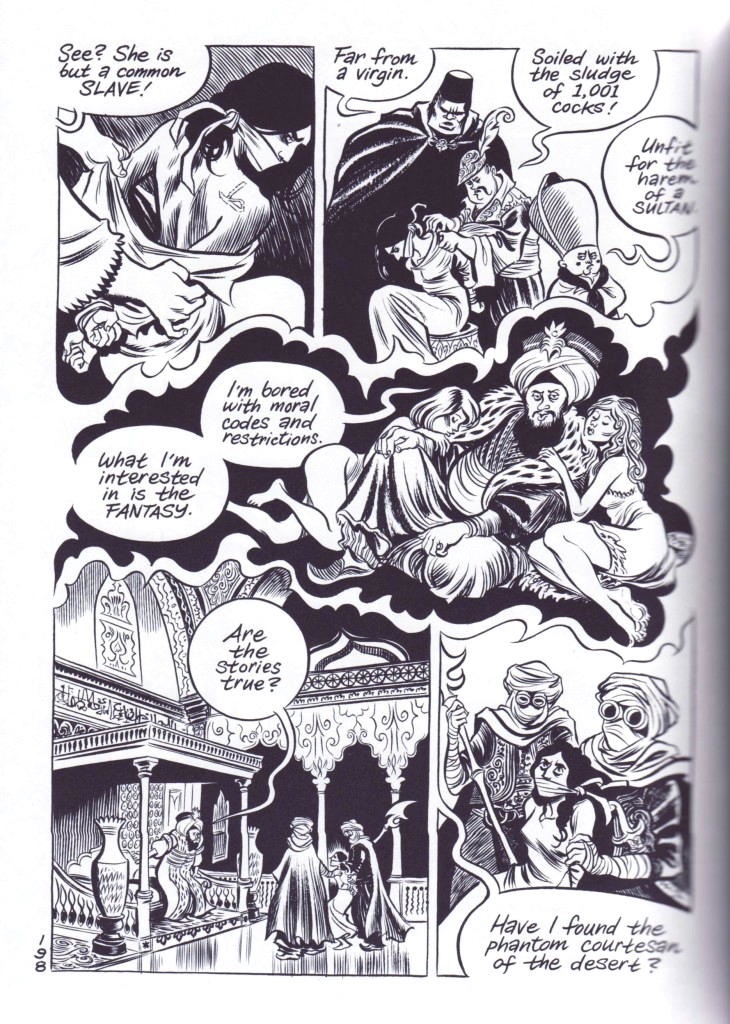

As for the charge of Orientalism, I knew it was going to come up no matter what, so why not embrace it? More broadly, I’ve always liked genres that have a degree of exploitation to them like horror films. They play on these really crass and appealing elements that also exist in 1,0001 Nights or French Orientalist paintings. It was fun to think of Orientalism as a sensationalized genre like Cowboys and Indians, which is a very poor representation of the reality of the American West, but fun to think of as a fantastical genre. And at this point in history, most people who watch things in the Cowboys and Indians genre totally realize it paints an inaccurate image of what the West was like … well actually you know there are people who watch cowboy films and think that’s what it must have been like. In fact, I’m pretty sure George W. Bush is one of those guys whose political beliefs are shaped by those films.

ND: I’m familiar with French Orientalist paintings and it feels that you are expanding on the snapshots those painting provide — like the scenes of Habibi that take place in the Slave Market or in the Sultan’s Palace — but those images are very loaded with this implicit “White Man’s Burden” element. In other words, we need to save the Arab women from the Arab men, and that’s how the French imagined “the Orient.” Did you ever fear that you were carrying the baggage of the medium by imitating that style? Specifically, I’m curious to know how you set a limit for yourself when sexualizing Dodola to avoid reducing her to simply another exotic Arab woman in Western literature?

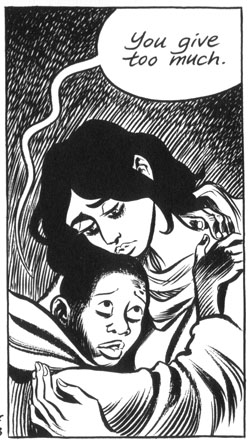

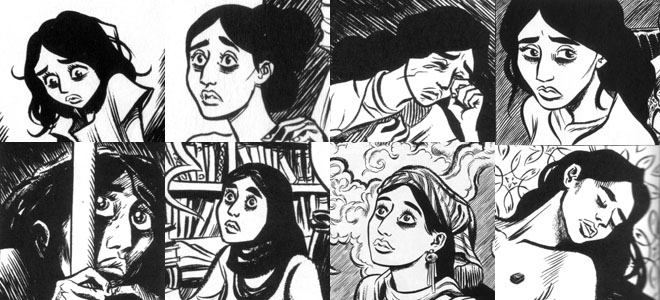

CT: I wanted to sexualize Dodola, because I wanted the reader to experience her through the lustful gaze of all men, and primarily the gaze of Zam. Hopefully the lust of Zam is transmitted in those drawings, and maybe at times the reader identifies with it or other times feels disgusted by it or ashamed by it, which mirrors the experience Zam was having. Throughout the book even the Orientalism is a commentary on exoticization. Which isn’t just about any specific culture or ethnicity, but a stereotype of what men do in general or what a lot of people do in romantic relationships. I’m examining American guilt and I’m examining male guilt. In male guilt there is so much of this energy of objectification and idolatry and eroticization. When I think of those French paintings I don’t see the “White Man’s Burden” of the French needing to save the beautiful Arabic women from their oppressors, I see the opposite: French men swarming in a perverted sort of way and trying to make fantasy reproductions of what those ladies look like under their hijab. I don’t think it paints the colonists in a positive manner, it makes them seem like these creepy little voyeurs.

ND: Especially because so many of those paintings were created without the painters actually going to the Middle East…

CT: Yes, exactly.

ND: Which makes those paintings problematic because those landscapes are imagined but purporting to portray reality. You’ve talked previously about trusting your subconscious in the creative process to guide you in navigating taboo. That makes for two distinct parts of Habibi: the subconscious imagined landscapes element that is the bedrock of Zam and Dodola’s love story, which you’ve noted was created aware of Orientalism, and then the research heavy elements of the book which deal more with the Qur’an. What I’m afraid of is that readers will take the more imagined and playful parts and give them the same level of plausibility as the clearly research heavy sections of your book. Now obviously you can’t be responsible for all your readers…

CT: That’s an understandable concern. For me it seems, on some level, a little silly that people keep talking about and examining Habibi as if it were some academic book, which it definitely isn’t. I keep labeling it as a “fairy tale” because that is definitely my intent. As much as an artist I want to strive to create comics as art or as literature, I’m still at my core just a cartoonist. Cartoonists want to make these exaggerated caricatured playful ridiculous irreverent drawings in some ways. I do feel reverent and respectful to elements of Islamic faith, but through the whole book there is a sense of play and self-awareness around the fact it’s still just a comic book. It’s super heroes in some ways. It’s Star Wars. But maybe the energy to focus on Habibi as an academic text is coming from outside the comics medium, where people are surprised to see more mature elements in a comic. In some ways the dialogue should also revolve back to the medium itself, which still has a satiric intent. I hesitate to say that, because I don’t want to say that Habibi is satiric towards any faith or religion. But comics are this sort of a self-deprecating medium inherently.

ND: I can speak to the academic tendency! For me, a lot of that has to do with the packaging. It’s this big tome and it’s by “Craig Thompson, author of Blankets,” and it feels a lot more “literary” just by virtue of packaging and the Pantheon label than more crass comics do. Do you ever feel a burden as one of a very few comics artist that is sold in Barnes & Nobles as well as local independent comic shops? You have those two worlds of fans that you have to appease and respond to.

CT: I feel privileged to be in that position. Since I’ve started my career in comics I always wanted to extend to a broader audience. I always felt that comics as a medium was untapped in terms of audience potential and that I was being held back by a lot of the retailers, distributors, and the attitude of fans in the industry. I definitely wanted to embrace this little fad in publishing of “graphic novels” because it feels like a window to extend comics to a bigger audience. I was excited to bring comics outside of the weird collector’s world. You know there’s been these different explosions in comic’s history of interest in the medium, but they’ve always seemed real tied up with the speculator culture. For me the bookstore is taking it back to the mass arts roots, like the Daily Newspaper, something that a common reader has access too and stumbles on and not just sequestered to a little cult Indie following the way an obscure punk record store would be. And I love buying a lot of those “tome” like products…

ND: Me too! When you’ve talked previously about about the goal for Blankets being 500-pages before you even had the story, I get that as a collector and fan of books in general.

CT: But I would like to create more modest projects too. Maybe naturally Habibi had to be this kind of book as a follow up to Blankets, because there was so much expectation of this as my “sophomore effort.” I don’t know, I think it also happened because of the emotional space I was in at that point in my life. I was being reclusive and in my Salinger phase. It would have been strange to emerge from that with something less.

ND: You’ve mentioned Joe Sacco as an influence. I don’t know if you understood it this way, but I found a lot of the Qur’anic elements to be a more Sacco-like project that had you looking at the footnotes of Suras and Haddith to pull out a really interesting research thread. Those are the parts of Habibi that I felt were most in your voice. I wonder if you ever had more of a desire to work in that vein as opposed to fiction? And jumping off that, our mutual friend Edward Said writes about the need for authors to “catalogue personal inventory” which in a very basic sense is a call for the author to put themselves in relation to the text in writing which creates a space for readers to know where the author is coming from. This is especially crucial in writing about the “East” from the “West,” which Sacco seems aware of by putting himself in his comics with obscured glasses; he is drawing in his subject position. Have you ever thought more about if post-Habibi you’d attempt a project more explicitly like that?

CT: You know what they say about dream analysis is that every character in your dream is a role that is played by yourself. You have to look at your dreams like “why am I stabbing myself with a butcher knife?” and you can’t judge any character because they are all representations of you. I feel similar about fiction. I can see parts of myself in pretty much every character in Habibi, even the ugly ones. For example there is one of the eunuchs that is creepy, more bad cop hijra, and I tried to draw that as a gross drag version of myself. I thought, what would I look like if I was a hijra and I focused it on my features. So there you have a character who is supposed to be a ridiculous hijra version of myself. Elsewhere I certainly saw myself in the fisherman, Noah. The Sultan, a lot of my female readers are disturbed and disgusted by him, but most of my male readers think he’s hilarious and identify him as a caricature of male sexuality in general. I can see that. I was playing that up for laughs for myself, like this is the way guys think a lot of the time.

ND: It’s really illuminating to hear that. The Sultan’s one of the more problematic characters for me so it’s interesting to hear you recast him in that light. With the fisherman, and the recurring focus on the Abraham story from both the Bible and Qur’an, it seems that Habibi is a way for you to explore sacrifice and the role it plays in our lives. It might be hard to articulate, but why was that such an important thread for you at the time you were making Habibi? I mean the role of sacrifice in relationships must have been important if you agreed that you were going to spend 7 years on a project dwelling on it.

CT: Well that definitely coming from a more Christian angle. That’s something I was thinking about while working on the book. Other than obviously the core Abraham story, sacrifice overall is a bigger theme in Christianity and the shame and guilt associated with having someone sacrifice their life for you. But, personally at the inception of Habibi I was processing being a caretaker in a relationship. I was in a long romantic relationship where I was also a caretaker and those are conflicting roles: to be a parent and a lover simultaneously, which is what Dodola is to Zam. I’m getting off track… I was thinking a lot about how much these sort of guilt feelings that shape my spirituality are purely about coming from a Christian background. As I talked with a lot of Muslim friends I didn’t find they shared that same core guilt and shame and sense of martyrdom in their faith. Of course, if you look at Islamaphobic observations of Islam people think of suicide bombers and jihad. So there it becomes an idea of sacrifice and martyrdom.

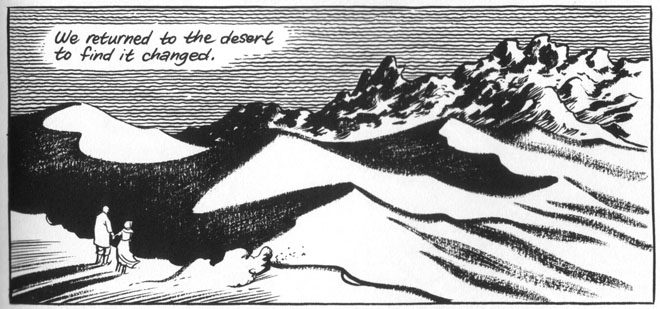

ND: As a Muslim myself, I feel the Qur’an is more about exploring love than extreme sacrifice. Although, there is Ramadan. Either way, I do really like that thread and how you weave it throughout Habibi. I want to switch gears to talk about Wanatolia and the decision to make it a timeless city, and how that factors into the end of the comic. I was hoping you could articulate how you had the decision for Dodola and Zam to return to Wanatolia and the reveal that it is modern in the western conception, even though at the heart of it is this palace which is backwards.

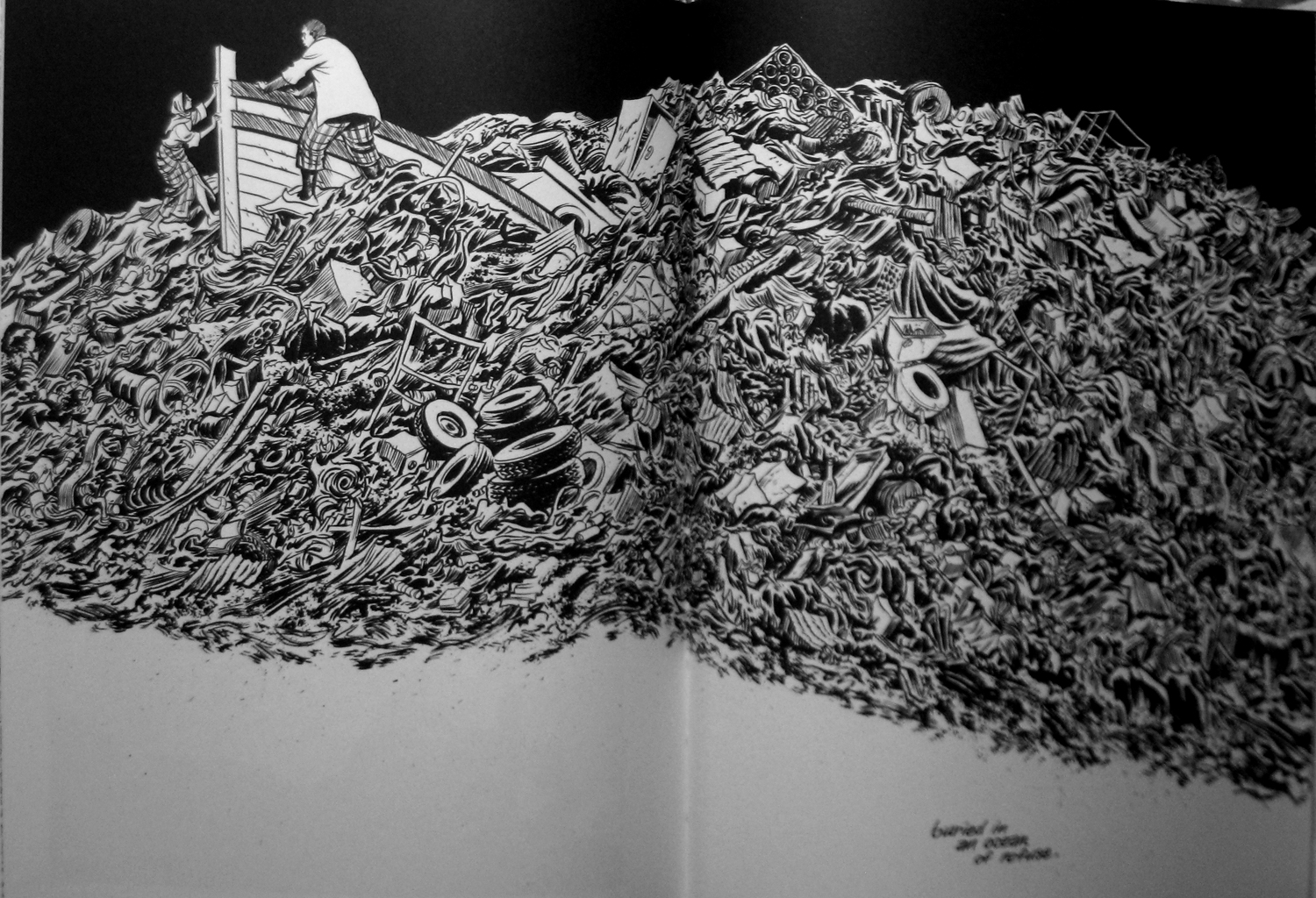

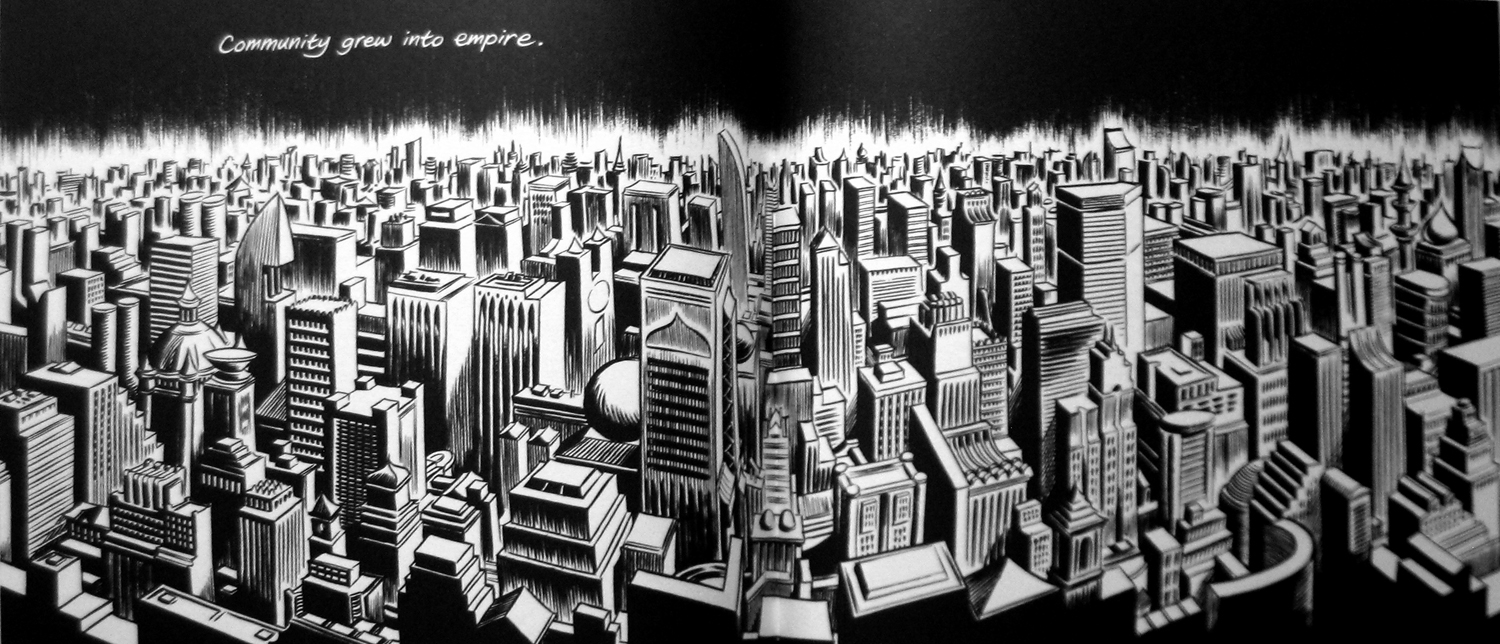

CT: In earlier drafts of the Sultan’s palace, I was mediating on the Bush administration and feeling like it was this sort of clueless world that existed outside of our own society. That was in the aftermath of 9/11 when you would see Bush off golfing somewhere. And certainly some Sultans during the Ottoman Empire have been critiqued historically for being clueless what was happening in society. That’s how the Ottoman Empire fell, the Sultans were living in a hedonistic cushion. By hedonistic I don’t mean they were sleeping with all their courtesans … it’s just the role of Americans and rich people in general that are totally oblivious of the state of the world. In terms of that clashing of the new and old world, that exists everywhere. If you travel to a developing country, you see people living in incredible poverty and living very simple lifestyles similar to 100 years ago brushing up against modernity and global trade. You can see how obviously our consumerist society is feasting off of poverty in their countries and how all our waste is there. Here we just consume and produce a lot of waste and then it sort of disappears and we don’t have to deal with it precisely because we are heaping it on to other people. And that’s a reality… I’m doing a fairy tale or parable version of that, but I don’t feel like it’s dramatically abstracted from the world we live in.

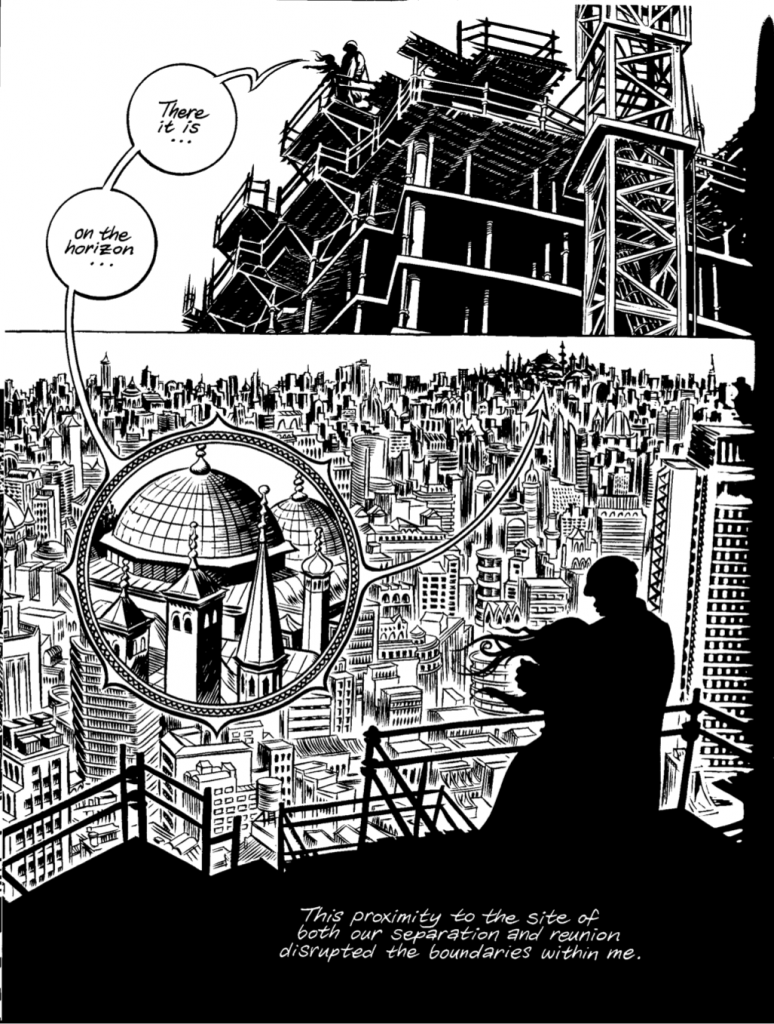

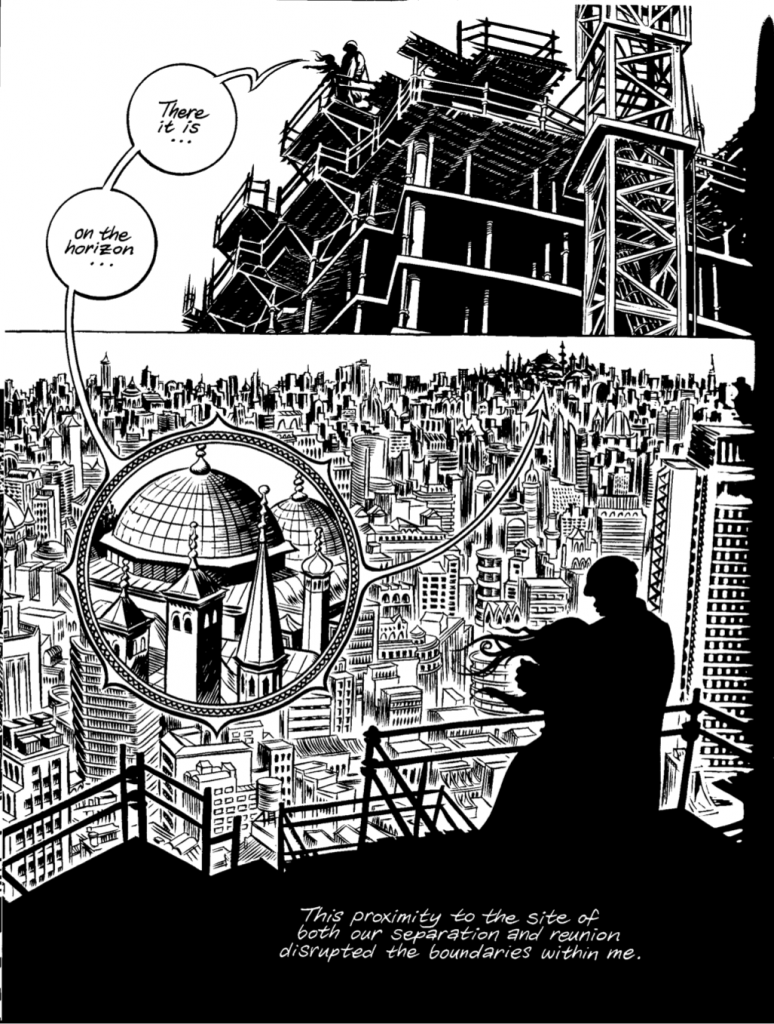

ND: For me the way it does feel abstracted is that there are no time markers and there are key fairytale elements. But then there’s that page in the book where you write “The proximity of the site of both our separation and reunion disrupted the boundaries within me” when Dodola and Zam see the Sultan’s palace from their new makeshift condo. The problem I had with this moment is the extent to which the backwardness of the “timeless palace,” as a place where they are both slaves, and the spot of their freedom, evidenced by that moment when Dodola takes off her hijab, are so close; I find it somewhat disrupting. And you don’t have to account for why me or any reader should feel disrupted by this revelation, but it is a shocking thing to have a modern city fueled by such tremendous backwardness that I don’t see justified in the text. Hearing the George Bush analogy at least helps put Wanatolia in a better context.

CT: Being in a city is about being in America basically. Having all these creature comforts and material comforts, but Dodola and Zam are coming from a place where they are also aware of suffering elsewhere. Which is sort of an adult experience, becoming more aware of the privileges you have compared to the rest of the world. It’s developing a sense of how you’re a passive participant in taking advantage of other cultures. And someone else has brought up the hijab thing to me, and for me the only real moment Dodola removes her hijab is when she does it to wrap up and clothe this little child at the end. For me that’s the only real moment and any other moment is incidental. If she has a hijab in one panel and off in the next, it mostly has to do with the comfortable space between her and Zam.

ND: The scene I’m specifically referring to is when she sees the “modern women” shopping in the city and there is a moment she takes it off then she gets accosted by lustful men a page later and she puts it back on…

CT: For me that scene is not “Oh! I realize I can be free like this women,” but more that she wants to fit in in this new context. She feels like an outsider, which I think the reader will perceive the other women that way because they seem to be from another world. And she does cover herself up because of this male gaze.

ND: This brings us back to how Dodola’s body functions primarily as a commodity, how even when the resources run out her body remains a marketable asset. I’m curious about if you ever felt aware of the baggage of her being sexed the whole time, even if that is purposefully through Zam’s perspective. If you ever felt wary of the contradiction between putting a feminist character into a societal position where there is perpetual forced sexualization of her body. I understand you as a “feminist” by putting Dodola out there in a way readers can sympathize with her, but then there’s an aspect of some readers maybe living out their own perverse sexual fantasies through the ways she’s treated. Do you see a danger in that?

CT: I don’t see a danger in it, but I definitely see a contradiction in it. So when you define me as a feminist, I’m OKAY with that, but there’s an irony in men claiming to be feminist to some degree. You can be sort of intellectually feminist, or claim to be, but there’s still a more primal animal instinct. You know, it’s the irony that some men who claim to be so intellectually feminist are the exact same people who are womanizers. Every time I meet another sensitive male it just bores me. And there’s nothing more painful than hearing a guy say he’s a lesbian trapped in a male body. So I’m exploring that contradiction: any man claiming he’s feminist is bullshitting, because your still animalisticly male. Again, I’m talking about heterosexual desires, but this crosses over to all sexual genders from transsexual people to homosexuals. That’s what I was exploring in my own life, that your sex drive is in conflict sometimes with ethical beliefs and you have to recognize both energies. If you put all the negative aspects of your sexuality in the shadow, then you’re probably going to fuck up and make some sort of mistake in your life, the way that politicians and televangelists do when we hear about their sexually deviancy. It’s the classic Catholic Priest scenario: if you don’t own up to your own shadow elements then they’ll emerge anyways and much more destructively.

ND: Without a doubt that sounds like a contradiction worth exploring. The problem for me is that for much of Habibi we go for long stretches of only seeing the shadow and then it becomes an issue of who’s casting that perverse shadow. When I hear you talk about it it makes a lot more sense holistically, but when I’m reading it as a stand-alone piece there is this disembodied voice of the author that makes it harder to accept those narrative choices. I guess that you exploring your own sexual contradictions gives readers a space to explore that to and maybe what I’m responding to is how uncomfortable that makes me as a reader feel…

CT: GOOD! That makes me happy I think. Maybe not happy, but it means the art has done its job if it makes the reader uncomfortable.

ND: When I heard about the project of Habibi I was expecting maybe a lighter fairy tale, but then as a reader you get confronted with slavery and rape and it’s all at the service of this endearing love story, but it’s pretty jarring throughout.

CT: And when I think of fairytales I think of those dark elements. It seems that all the great nursery rhymes, fairy tales, and children’s stories are full of those exact same dark twisted elements. It’s the tradition of the genre. And I’m not speaking of 1,001 Nights even, but Hansel and Gretel or Little Red Riding Hood.

ND: Well to pick up on that it seems that in order for you to call it a fairy tale it has to have a more happy ending. And you provide that by having Dodola and Zam reunited and creating a safe space for a new child, but did you ever have the impulse for it not be happy at the end? To just be brutal?

CT: Oh yeah. Definitely. I never wanted the book to have a cinematic Hollywood ending, and I wrote variations that were more cynical, but ultimately the end that was the most truthful was the far more optimistic one. That said, people see what that they want to see in the endings. With both Blankets and Habibi I’ve heard people say both that they were either super depressing or super hopeful. I find it very interesting when the reader imposes their own experience onto the endings.

ND: In Habibi there are these moments were you get a completely new character, like Noah the Fisherman, that feel part of their own complete story. Was that a product of the amount of time you were spending on Habibi and needing a new narrative voice to take a break?

CT: Noah was there from the very first draft. As I was working on the book a lot of people wanted me to remove him. They felt he was too much of a total aside and irreverent basically. But I really enjoyed writing him for my own sake and felt he was a necessary dash of levity in the midst of all the darkness and heaviness. For me he made me laugh a lot and there’s a lot of pleasure writing that character even though there’s an intense sadness to him. I did want the chapters to feel like their own graphic novels to some degree. I was very aware that Zam and Dodola would be apart for hundreds of pages, I wanted it to feel that way almost to the point you forgot about the other character at times. They only existed in this idealized memory. I like that in books where things wander for quite a while and you lose site of where you began.

ND: It’s definitely a powerful element that they go through so much change on their own and have to reconcile that when they are reunited. I’m interested in your fan’s reaction to Habibi and what readers have said to you about Dodola and Zam. Are they taking to them the same way they do a cute Chunky Rice?

CT: I think so actually! Yeah! Which is the greatest compliment as an author. I felt really attached to them and they felt like real people to me and that is the sort of response I’m hearing from readers.

ND: So if this book is coming from a place of post-9/11 guilt, which I interpret as Islamaphobia in the US, then do you think that Dodola and Zam were the direct product of that?

CT: No no no! They are unrelated to it at all. They don’t even seem like they’re created. They just kind of arrived from the subconscious fully realized. And they predate anything else in the book. They’re of their own making. Laughs.

ND: So they came with their geography and their own history?

CT: I knew they were child slaves from the start, but I didn’t know what kind of world they inhabited. And my research of slavery and randomly reading books about slavery pointed me in the direction of the East African/Arab slave trade that predated the cross-Atlantic slave trade by 700 years. As I was reading some of those research books they eluded often to 1,001 Arabian Nights which drew me towards that, and while reading Nights I became aware of the Orientalism in the Richard Burton anthology. Around the same time I started studying Islamic Art. But I did attach myself fairly early on to the Arabian Nights landscape. Right away I could see it for both its strength and weaknesses, but I thought of it as a genre that would be fun to work in like Superheros, Science Fiction, or Noir.

ND: But is just such a loaded genre…

CT: Yeah! Bring it on, right!

ND: And I think that’s ultimately my response: it’s hard separating you as a creator who’s clearly very sympathetic and is so good at humanizing characters — which comes across so well in the Qur’anic parts — and the fact that you are swinging around in this playground that is so deeply tied up in a history of otherizing.

CT: And ultimately I like the conflict between those two elements.

___________

This is part of an ongoing roundtable on Habibi and Orientalism.