Osvaldo Oyola and Kailyn Kent had an interesting conversation in comments about the X-Men and policing mutants; I thought I’d reprint it here.

I think you hit on something I have been saying for a while about the racial and sexual other in superhero comics – they have to prove their worthiness through violence against and/or policing of others of their kind. The X-Men (esp. early X-men, but definitely into Claremont’s classic run) just reinforces this and is all the more egregious by white-washing the difference to begin with.

Xavier could only be MLK if MLK had armed young black soldiers that went into black communities to violently combat the threats to black middle-class respectability that he cared about above all – in other words, it doesn’t jibe with MLK both ideologically and in practicality.

Osvaldo, that’s a really good point. X-Men makes it particularly evident, through its use of an ensemble cast of many superheroes and supervillains. But this self-policing, masochism and assimilation seems like a foundational part of the genre. And one that I think comics is congratulated for– the ‘nobility’ of a guardian who loses his ability to ‘be one’ with the society he’s protecting. Or, how pure these fantasies are, coming from the brains of marginalized Jewish teenagers at the turn of the century.

There’s convincing evidence for superheroes stemming out of the stage and dime-novel melodramas (Alex Buchet’s work, for example.) Melodrama, when not fully occupied with sawmills and speeding trains, navigates a weird zone between comedy and tragedy– an unreconcilable schism is presented between the protagonist and society, which the narrative itself can’t solve, and so absolves it through a unifying trauma which stitches everyone back together. This is often the trauma of near death to a female body, the heroine lies freezing on an ice floe speeding towards a waterfall, etc. etc. Once she is rescued, it magically doesn’t matter that she’s still a fallen women, when the society that embraces her hasn’t come close to amending their value system.

To wind back to the central concept– while I’ve heard ‘secret identities,’ and ‘serialized thrills’ spouted as reasons for superhero comics to be melodramas, I’ve never heard them discussed as assimilationist fantasies. But it fits really well.

And melodrama is important! Probably no other narrative mode has had a great as influence on society and politics in the last few centuries, and melodrama increasingly pervades political and campaign imagery. Melodramas are ‘people-movers,’ and make whatever story they’re conveying especially sticky.

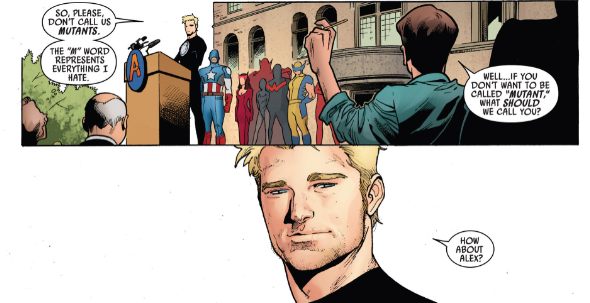

The image here is by Rick Remender/Oliver Coipel from Uncanny Avengers #5.