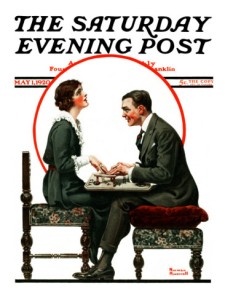

I bought the Ouija board from the toy store in our local mall, and my wife set it up in our dining room. She was teaching James Merrill’s The Changing Light at Sandover, a postmodern epic composed from séance transcripts, and she wanted to give spirit communication a whirl. We rested our fingertips on the plastic planchette. Merrill and his lover used an upside-down teacup and could barely scribble each letter of dictation before it skidded to the next. Our planchette dribbled a few centimeters southwest. The yellow legal pad lay blank under my wife’s uncapped pen.

I could blame the board—a fault in the ectoplasmic wiring—but when she tried the experiment with her poetry students, a half dozen ghosts elbowed onto their seminar table. So I’m officially adding “talks to the dead” to my list of failed superpowers.

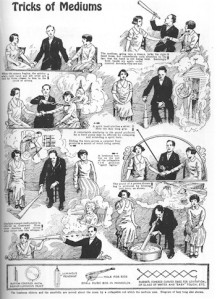

A real medium wouldn’t touch a planchette anyway. Their hands would be tied behind their backs as proof of their superpowers. And forget teacups. “A great physical medium,” writes Sir Arthur Conan Doyle in The History of Spiritualism, “can produce the Direct Voice apart from his own vocal organs, telekenesis, or movement of objects at a distance, raps, or percussions of ectoplasm, levitations, apports, or the bringing of objects from a distance, materializations, either of faces, limbs, or of complete figures, trance talkings and writings, writings within closed slates, and luminous phenomena, which take many forms.”

A list worthy of Professor X, and Doyle, creator of super-rationalist Sherlock Holmes, witnessed them all. His second-hand accounts are even more uncanny. Psychic researchers theorized that Eusapia Palladino grew a third “ectoplasmic limb” in the dark of her séance room. “Now, strange as it may appear,” explains Doyle, “this is just the conclusion to which abundant evidence points.” D. D. Home he dubs a “wonder-man,” but Elizabeth Hope, AKA “Madame d’Esperance,” is my favorite of his super-psychics. Observers documented her powers of Partial Dematerialization, which may lack the BAMF! of Total Teleportation, but she could also materialize the spirit entities of an infant and a full-bodied “feminine form” named Y-Ay-Ali who held hands with séance participants: “I could have thought I held the hand of a permanent embodied lady, so perfectly natural, yet so exquisitely beautiful and pure.” Y-Ay-Ali then “gradually dematerialized by melting away from the feet upwards, until the head only appeared above the floor, and then this grew less and less until a white spot only remained, which, continuing for a moment or two, disappeared.”

Some cite 18th century mystic vegetarian Emanuel Swedenborg as the father of Spiritualism (he trance-traveled to Heaven and Hell and all of the planets of the solar system and several beyond), but like most historians Doyle looks a hundred years later. In 1848, twelve- and fifteen-year-old Kate and Margaret Fox opened the door to the beyond in Hydesville, NY. They grew up in the western New York region that millennialists, Mormons, and sundry utopians “burnt over” during the Second Great Awakening. The Fox sisters were late-comers to the anti-rationalist revival, equivalent of Silver or even Bronze Age superheroines, but they created their own genre as the first séance mediums when the devil came knocking on their bedroom floor. They later confessed that “Mr. Splitfoot” was an apple tied to the end of a string, but by then they were both alcoholic celebrities in an international movement that had spawned as many imitators as Action Comics No. 1.

Believers like Doyle claimed such confessions were forced and therefore false. Doyle also believed in fairies, famously falling for another pair of children’s selfies posed with book illustration cut-outs. The Partially Dematerializing Ms. Hope was exposed too—“literally,” as debunker M. Lamar Keen puts it—when a séance sitter grabbed at some ectoplasm and instead caught the medium in “total dishabille.” Except for the occasional TV psychic or afterlife memoir, the flimsy world of Spiritualism has been stripped naked for decades. I doubt A. S. Byatt is a current convert, but her historical novella The Conjugial Angel pairs a warm-hearted fake with a dead-to-life spirit-seer. That’s the faker/fakir dichotomy that’s haunted the genre since its debut.

I used to teach Byatt in my first-year composition seminar “I See Dead People,” but my students usually prefer Henry James’ Turn of the Screw. His father, Henry Sr., was a Swedenborgian theologian and his brother William a psychic researcher. I’ve never tried to materialize the masculine form or Henry Jr. to ask what he did or did not believe, but his governess-narrator is my favorite study in Total Ambiguity. Is she a righteous medium battling demonic ghosts for the souls of her innocent wards? Or is she a victim of those not-so-innocents who, like fairy-fakers and foxy Foxes, are too damn good at playing grown-up. Or is the woman just batshit crazy? Her imagination seems overcooked on fairy tales romances and Biblical struggles of good and evil—comic books basically—but however you diagnose her, the governess (James never unmasks her name) casts herself as a superheroine blessed/cursed with superhuman abilities.

James Merrill never confessed the nature of his ghost-chats either. Could teacup transcripts really produce a 560-page poem? Were he and his lover knowingly collaborating? Did the spirit of a first-century Jew named Ephraim abandon their hand-drawn Ouija board to enter his lover’s body for a séance threesome in bed?

I haven’t been entirely forthright either. I used my non-séance in a short story once, and now I can’t distinguish my memories from my cut-out inventions. I can, however, report as a verifiable fact that the Ouija board is currently sitting atop a bookcase in Payne Hall. My wife refuses to keep it in our house. Her superpowers must be sibling-triggered, because a bout of planchette-skidding in her sister’s dining room ended in a telekinetically slammed door and a flock of cousins screaming up the stairs. I was in the guest room reading. But, like Doyle, I believe every word.