This post first appeared on comixology.

_____________

In der Mandel — was steht in der Mandel?

Das Nichts.

Es steht das Nichts in der Mandel.

Da Steht es und steht.

Im Nichts — wer steht da? Der König.

Da steht der König, der König.

Da steht er und steht.

Judenlocke, wirst nicht grau.

Und dein Aug — wohin steht dein Auge?

Dein Aug steht der Mandel entgegen.

Dein Aug, dem Nichts stehts entgegen.

Es steht zum König.

So steht es und steht.

Menschenlocke, wirst nicht grau.

Leere Mandel, königsblau.

Mandorla

In the almond — what dwells in the almond?

Nothing.

What dwells in the almond is Nothing.

There it dwells and dwells.

In Nothing — what dwells there? The King.

There the King dwells, the King.

There he dwells and dwells.

Jew’s curl, you’ll not turn grey.

And your eye — on what does your eye dwell?

On the almond your eye dwells.

Your eye, on Nothing it dwells.

Dwells on the King, to him remains loyal, true.

So it dwells and dwells.

Human curl, you’ll not turn grey.

Empty almond, royal-blue.

As with all of Celan’s poems, this one is hermetic: a series of riddles. You can almost hear Gollum asking these questions to Bilbo, creeping closer and closer. “What dwellsssss in the almond, my precious? What dwellssss there?” And behind the questions, as behind Gollum’s, is the weight of time and the dark.

That weight, for Celan, is here seen through an image, the mandorla, which moves in and out of the poem, not answering the questions so much as shadowing them. In some sense, the poem is a straightforward description of iconography; inside the mandorla, or the almond, there is nothing; it’s an empty space, as you can see in the picture from Chalice Wells at the top. And that empty space, or nothing, symbolizes or holds Jesus, the human and divine king. In the last stanza, the mandorla also becomes the eye itself —of the person looking at the symbol of God, or of God looking at the looker. The almond then is both image and reality, each nestled in each like reflections in facing mirrors retreating and retreating into the flat space of eternity.

The original German text itself seems arranged in a series of reflections or doublings.

Da steht der König, der König.

Da steht er und steht.

“der König” there is repeated not just for emphasis, but because the King is not one, but two, like the circles of the mandorla overlapping. He’s both there and an echo, something and nothing.

One possibility as to where the circles meet, or what is in the almond, is the Shoah. Celan survived the Holocaust; his parents both died in it.. In that context, for the Jewish atheist Celan, “Judenlocke, wirst nicht grau” could be a statement of (someone else’s) faith — Christ, a Jew and King, stays young forever. It could also be an elegy of sorts for Celan’s parents and all the victims of the Shoah. Your hair doesn’t turn grey when you’re dead.

I think it would be wrong to see this just as a Holocaust poem, though. What Celan took from his personal tragedy was not confessional despair. Instead, the Holocaust for him becomes the impetus and the center of a collapse of meaning. It is not just that you cannot represent the Holocaust; it’s that thinking about the Holocaust reveals the impossibility of any representation of anything. Speech teeters on the edge of silence, and the final answer to every question is nothing;

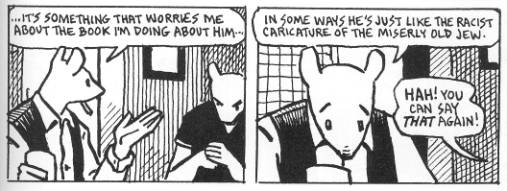

Language, then, comes apart. But what about images? The mandorla is a kind of representation as well; it’s a visual symbol. In language you can’t see what is in the almond, perhaps, but in a drawing you know whether it’s nothing or Jesus or, in a locket, a face or a memory. If you can’t tell, can you show?

Maybe you can…but to what end? Language slips away through the deferral of meaning — the almond is nothing is the King is God is the Holocaust is even Gollum if you want, and all those sliding sibilant syllables. Images don’t defer, though; they dwell and dwell. They’re so stable you can see them even through language. The mandorla that curves around the poem is clearer than the poem itself.

But that clarity itself defies meaning. What you see in the mandorla is your own eye, unaging and blank. The King in the almond is a God who doesn’t move. His borders are drawn, and a God bordered in a nutshell isn’t a God at all. He’s a nothing, an image. The word escapes, the picture stops. “Mandorla” empties not just language, but the space between image and language. Obviously, “Mandorla” isn’t a comic. Instead, it’s the non-space left when the parts of a comic, — the name and the face of God — intersect and are gone.

[insert video of Paul Celan reading Mandorla: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X31Dp_7tVG8 ]