This essay first appeared on Splice Today.

______________________

Conventional wisdom would have it that Peanuts fell off precipitously as the strip entered the 80s. On the evidence of the latest volume of The Complete Peanuts, covering 1979-1980…well, conventional wisdom may have a point.

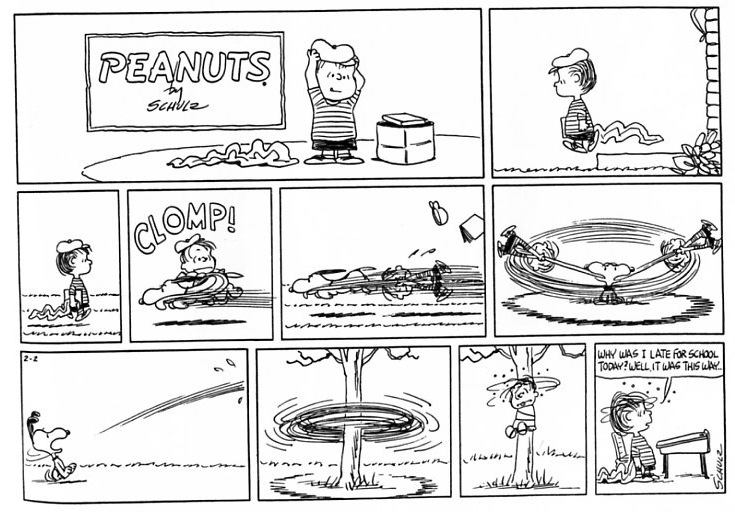

The art in Peanuts had by the 80s long since declined from it’s early heights. Over the decades Schulz’s line had lost much of its nimble dexterity — so much so that it’s easy to forget how good he was back in the day. The whole point of this sequence from February 1964, for example, is the kinetic elegance of the motion lines.

By 1979, though, the battle between Snoopy and Linus has been robbed of its energy; all that’s left is a couple of almost apologetic motion scratches and an anti-climax. The fight has gone out of the art.

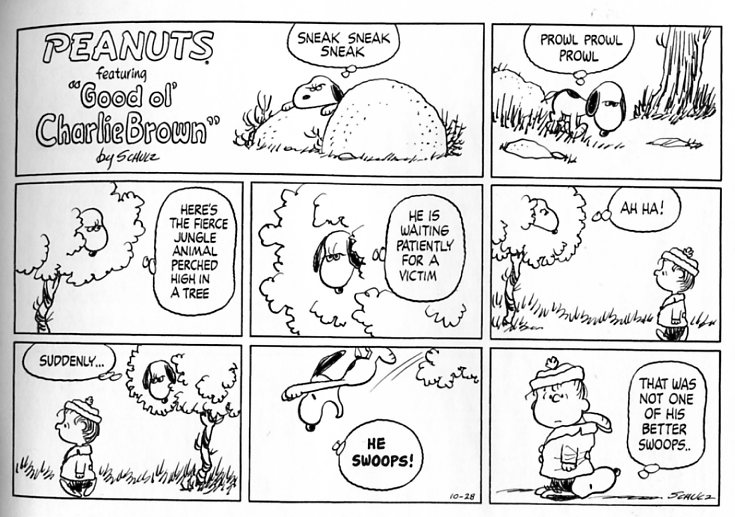

In the mid-70s, Schulz made up for the relative tameness of the illustration with some of his most adventurous narratives. For example, one storyline which stretched through September and October of 1976 began with Peppermint Patty’s relatively innocuous effort to go to private school. It then quickly spiraled into escalating heights of absurdity, as Patty went to the Ace Obedience School for dogs and finally the tale ended in an epic battle with a cat which Patty had mistaken for her attorney, Snoopy. In fact, at the end of the story, Schulz seems almost to be taking advantage of his reduced drawing skills, moving the most frantic action off-panel to suggest a spectacular conflict which can only be imagined, not rendered.

In 1979-80, though, the long meandering narratives have gone the way of the exciting line work. There are still some extended stories, but they lack the snap of the sequences from just a few years earlier. A storyline where the kids end up at an Evangelist camp has an unfortunate air of hesitant moralism. Schulz’s world is too small to even fit adults, much less adult opinion, and his hesitant jabs at the Moral Majority seem like they were faxed to him by a focus group. Berkeley Breathed would soon wed something of Schulz’s aphasiac genius to political commentary…but whenever Schulz himself tried for relevance, the results were ugly (*cough* Franklin *cough*).

One muffed storyline could happen to anyone. But Schulz increasingly relies on recurring gags which simply aren’t that funny. The chief offender here is Snoopy’s Beagle scout troop. Snoopy leads Woodstock and several other birds over hill and dale, up mountain and down, making cute little quips about angel food cake. It’s not that it’s horrible, exactly — I chuckled at many of these strips. But, at the same time, the conceit really plays against Schulz’s strengths. The birds are all visually interchangeable, and because they speak in bird language which only Snoopy understands, they don’t have the strong distinctive personalities of Schulz’s other players. And without those distinctive personalities striking off each other, it’s hard to generate much conflict or interest. You basically end up with Snoopy talking to himself in front of a bunch of ciphers. A little of that goes a very long way.

And yet….while there’s no doubt that this volume is an inferior work of genius, there’s also no doubt that it is, still, the work of a genius. In some ways, the genius shines through even more brightly when the general level is lowered. In the 50s and 60s, Schulz operated at such a consistently transcendent peak that you could start to take him for granted. Here, though, there are dull patches to remind you just how good the good parts are. Without the distraction of the motion lines, for example, this Sunday strip we looked at before:

attains a purity of fuddy-duddiness. The whole comic comes down to that last panel, where everything has misfired. There’s no glorious rush, just a stumbling, thumb-fingered, doofy perfection.

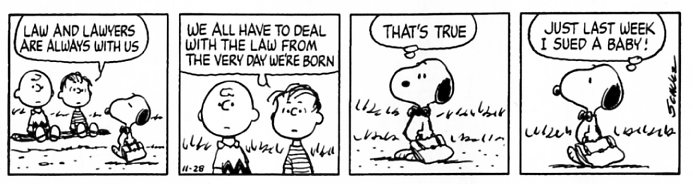

And then there’s this:

That left me laughing helplessly. It’s a platonic Peanuts joke; that last line doesn’t even rise to a pun. Instead it’s simply flat, unexplained surreal nonsense, delivered by a dog with a giant nose and a blank expression.

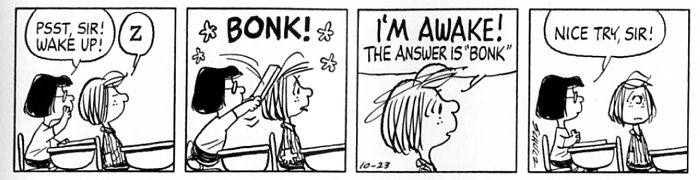

There’s no doubt that Schulz lost his way in the 80s. But his strip was always about losing its way. As he grew doddering and inconsistent, he moved closer to the doddering inconsistency at the core of his art. The pleasures in this volume are fewer, but, for fans at least, when they come they have a special bonk.