A weepy blog post composed of questions:

•One of the most interesting discussions that took place at the ICAF conference I attended a few years ago in White River Junction concerned the question of readers’ emotional responses to comics. I forget who exactly was involved in the discussion but I remember distinctly that there was somewhat of a consensus on the notion that comics are not a spontaneous or passionate medium. One reads comics analytically, obsessively, but not immersively. One rereads comics over and over, and might form intense emotional responses to the stories and characters, but not in the same spontaneous and overwhelming way we might experience when reading novels or watching films. Comics scholars in that room seemed to agree that, generally speaking, it is not common to weep in response to a comic or graphic novel. I mostly agree, although I hope to be proven wrong. The question has been asked many times before, but I ask it again: which comics have made you weep?

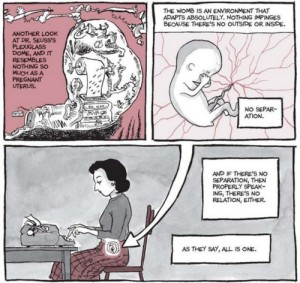

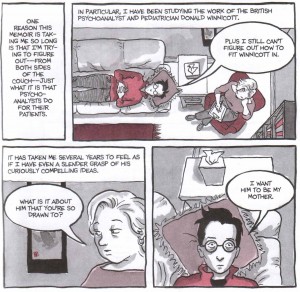

•I wept a few times while reading Alison Bechdel’s Are You My Mother? It’s hard to understand why her autobiographical comic moved me to such a great degree when I don’t identify with the author’s alienated relationship to her mother and, more to the point, I find metafictional writing intellectually interesting but not moving in any kind of spontaneous weepy kind of way. So, I’d like to understand, why did Are You My Mother? make me weep (on an airplane, in front of strangers, no less)!? I don’t have an answer to my question but I do have more questions.

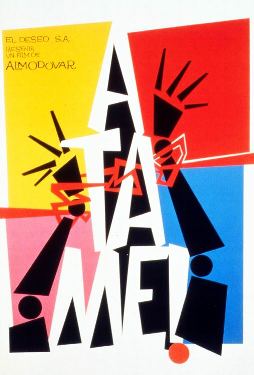

•As a gay man, I often find naturalizing maternal/paternal narratives, especially those that involve legacy or inherited guilt/pride/whatever to be silly and alienating; it’s a culture I was violently excluded from, being from a born-again Christian family. At the same time, like anyone, I have inherited various legacies from my family and am as vulnerable as the next person to stories about generational transmission (guilt, abuse, pride, shame, etc.). Usually such stories are intellectually interesting but not moving enough to bring me to tears. My critical capacities shut the schmaltzy response down before it can materialize. I find Wes Anderson films utterly intolerable, even though I admire his artistry, to give you one complicated example. So, the only way I can understand my response to Bechdel’s Are You My Mother? is by comparing it to the very similar emotional response I experienced while watching Almodovar’s All About My Mother. Is it a coincidence that both works are about mothers? Or that both works are intensely metafictional and citational? Am I just being disingenuous about my mommy issues?

•It’s a question I could not get away with asking in a scholarly article, but one worth asking nonetheless: do mothers and metafiction have something to do with one another? Is there something maternal about metafictional structures? Is there something metafictional about the way we relate to our mothers?

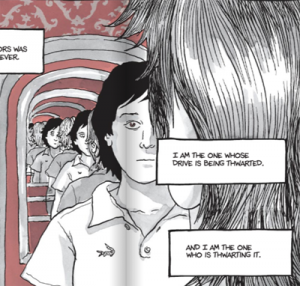

•Both Almodovar and Bechdel are interested in acting. Bechdel’s mother is an actress who, at times, plays a mother. Almodovar’s mothers are always actresses who usually play bad mothers. What is it about the mother-as-actress figure that moves me to tears? I suspect it has something to do with Freud’s fort-da, that the mother is somehow both unavailable and eternally available as a representation. Does the fact that mothers can be played by actresses disturb our understanding of motherhood as somehow natural?

•There may be a narratological term for this, and please let me know if there is, but one of the aspects of Bechdel’s and Almodovar’s metafiction I find deeply moving is the deliberate layering effects. Actresses play mothers; mothers play actresses; men play women; women play women. The play within the play is only the beginning. For Almodovar, All About Eve and A Streetcar Named Desire become the grounds for a series of fictional layers (fiction providing the grounds for further fictions), while for Bechdel, it is the works of Virginia Woolf and Donald Winicott, among others, that serve a similar purpose. All of these layers of fiction bring attention to the melancholic unavailability and tragic loss of some kind of original femininity/maternity. The fictional copy brings attention to the fact that the original is not, and has never been, available. Children cope with the unavailability of their mothers (be it a psychological or simply situational unavailability) through increasingly complex layers of transitional objects, all of which enable the child to grasp the reality of absence while also providing comfort in the form of a substitution. These layers are essentially fictions, and I think this might be where we can find a tie-in between metafiction and mother-child object relations. We are all moved by stories that engage mother-child object relations (unless we are psychotics) but why is it that I find myself weeping most weepily in response to stories that construe mother-child object relations in metafictional terms?