There’s a major comic market in France. Since I don’t know the numbers, I hesitate to claim it’s a bigger industry than the US’, though I’d like to imagine so. My argument: like manga in Japan, comics in France are seen as targeted to a wider audience, and not just to what is perceived as an audience of kids. It’s not quite to the extent of Japan’s market, where there are comics for as many social demographics that exist, but in France, some kid’s grandparents are as likely to read and enjoy the same comic book as their 15-year old grandchild.

I had a period where I was wholly engrossed by US comics, around the age of 12-15, but I had been indoctrinated into comics years before (by Astérix and Tintin and before that, Topolino, the Italian-language Mickey Mouse comics, which is another story of comics transcending the target audience perceived in the USA), and although my romance with superheroes ended in my early teens, my love for the French comic industry in general continues far into my adulthood.

The attitude of French comic lovers from France — where there is a substantial market for manga and US comics, known there as “comics” (to differentiate how the French call their comics “bandes déssinées” or “BDs”) – is that their native-language comics require an immense amount of work and planning to put out… perhaps in unspoken contrast to their perception of how much less work manga or “comics” require to complete, or perhaps not. Sure, it’s part snobbery, part elitism, but take a look at any French comic book and you can tell that at least there’s a more important investment financially in being a fan: Every single BD is hardcover, from the original Lucky Luke‘s to the final volume of De cape et de crocs, and as such cost around 13-15 euros a piece. There are never any ads in any French BD, and there’s a sense that the population in general sees the medium in a more artistic light than how Americans view the comic industry – take a look at most reviews of French BDs on amazon.fr and you’ll get far more florid, well-spoken, nigh-erudite examinations of the artistic merit of the art style, the story pacing, and the cultural significance of a comic series (take Aldebaran as a good example), as opposed to the kind of reviews you’re likely to read on English-language Amazon where people can’t get things like “their” vs. “they’re” straight.

But all this “high” art, with all of its veritable or romanticized artistic merits, does come at a price beyond the financial one: The next issue of a BD series in which you were left with a cliffhanger revelation on the last page of the previous book might not come out for years. In France, it’s viewed as nothing short of a well-oiled machine in the extreme when a BD series puts out a new book every year. In fact, it’s borderline suspicious. Take Christophe Arleston, one of the biggest names in BD from the past 15 years. He’s got his scenario-writing fingers in no fewer than five pies at once, with some of those pies baking a new slice every year, much to the criticism of the French public, who generally believe his work has become about cranking out quantity over quality, and has become rehashed, shallow, recycled. formulaic pulp as a result. In contrast, the superb, highly celebrated series La quête de l’oiseau du temps‘s first book was released in 1983, and 2010 saw the release of only the seventh book, including an 11-year gap between books 4 and 5, and a nine-year gap between books 5 and 6. Compared to that, the release schedule of the next book of a series like “Harry Potter” would seem like the next issue of “Vogue.”

I’ve always wondered how an industry could sustain itself with such a business model; how people wouldn’t get so aggravated or simply just lose interest during the years of wait between books 2 and 3. French comic shop owners point out that there generally aren’t any deadlines on BD creators, and that the industry isn’t quite so successful to allow the creation of BDs as a livelihood to more than a few artists.

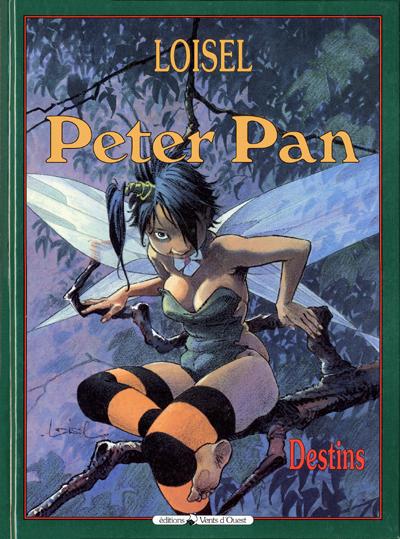

There’s even a bigger drag to having to wait, though. Sometimes where a series ends is far different than where it began. The series that will live in the most personal infamy is Régis Loisel’s re-interpretation of the origins of Peter Pan (BD) It took some convincing to read this series, but that it was a darker, more adult-oriented re-imagination of the famous tale, and that it was made entirely by part of the creative genius team responsible for the essential “La quête de l’oiseau du temps” made me take the plunge.

In Loisel’s version, Peter is the bastard son of an abusive, alcoholic whore in 19th Century London. After meeting a fairy in the slum where he lives, Peter manages to escape to Never Neverland, where he ingratiates himself with the fairies and satyrs there. They elect him their leader after he helps fight off the pirate who later loses his hand and becomes Hook. Hook is hanging about in part to find treasure purportedly hidden in Never Neverland. There’s also something to do with Hook having had an manipulative affair with one of the islands fatter mermaids, who’s still in love with him.

Loisel’s first “aha!” creative spin on the tale comes from the origins of Peter Pan’s name. In the story, it is derived from Peter’s own, Christian name, and the name of his short-lived best friend and leader of Never Neverland, Pan (yes, just like the mythical satyr), who is killed during the struggle with Hook. Pan’s death leads to Peter becoming the island’s leader, and he takes on his friend’s name as an homage.

Loisel’s “Peter Pan” first four volumes were released between 1990 and 1996, a relatively brisk pace for the French market. As such, the story is interesting, creative, and most importantly, gives a sense of a well-progressing narrative.

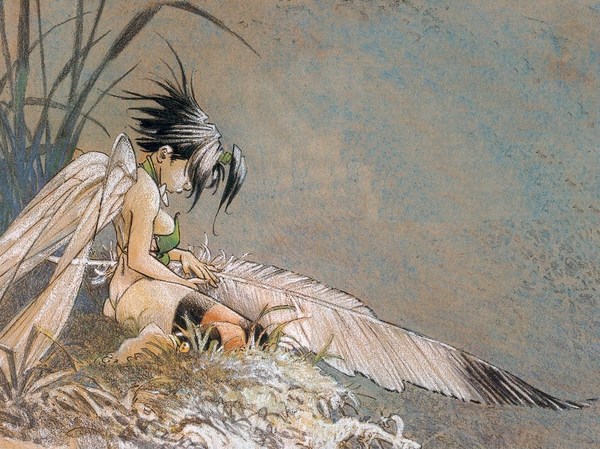

By the time volume 5 was published, five years had gone by since volume 4, and things were starting to take an odd turn. There was a lot more focus on a side story involving Jack the Ripper back in London, and an arc portraying Tinkerbell as a manipulative, selfish, careless creature responsible for the deaths of Never Neverland residents who got a little too much in her way. The story still floated, but the feel that books 1-4 were one entity, and that book 5 was another was strong.

2004 saw the release of the sixth and final volume of the series, which cemented the sense of bewilderment. Now, the Jack the Ripper side story became central, and it was revealed that Tinkerbell had been repeatedly rubbing out her rivals. She never suffered for her actions, though, in part because it turned out that Never Neverland had the effect of wiping clean any inhabitant’s mid- to long-term memory. This meant that no one could remember where anyone came from, why they were there, or how their situation came to be… and that included Peter’s tale and Peter’s own personal recollections. It turned out that the tale of Never Neverland had been on constant repeat since time literally immemorial, and that all of its inhabitants were caught in its temporal memory-loss loop.

It’s not even how the series ends with Jack the Ripper stalking and killing another victim (I seem to remember it being Peter’s mother), or that the entire series took a major emotional turn from a boy’s tale of triumph over adversity and his rise to power. It’s that the story changed tone and content to such a degree that it not only felt like two separate stories, it felt like the author had taken too long to complete his vision, had grown weary of the work he had made in the ’90s, and wrapped it up with some out-of-left-field randomness that felt convoluted, obscure, half-baked and rushed. Essentially, whatever had been built during the successful first 4 volumes had been utterly crapped on in the final 2. The first movement’s mood is of edgy adventure, of progressive storytelling; the mood the reader is left with on the second movement is of depression, that the world is a bleak place with no outcome, that no wrong is righted, all of which is communicated with a strong lack of closure.

Today, in research for this article, I looked up the story of this series online, and discovered an interpretation that Loisel’s intention with the inclusion of Jack the Ripper was to stipulate that Peter Pan and Jack the Ripper were in fact one and the same, which, if accurate, is a major plot point that I was utterly clueless to until having read that (though it helps explain some things). This does little to change my opinion that Loisel’s “Peter Pan” is one of the most irresponsibly wasted efforts I’ve come across in my comic reading life, one whose rampant disregard for its own craft and narrative tone soured my mood for some time after. Considering its horrific procession from interesting work to obvious cut-and-burn job, it is my vote for Worst Comic of All Time.

_____________

Otrebor is a musician from San Francisco whose most notable bands are Botanist and Ophidian Forest.

Click here for the Anniversary Index of Hate.