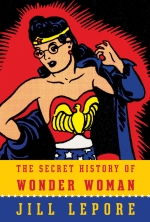

I reviewed Jill Lepore’s book The Secret History of Wonder Woman over at the Atlantic a little bit back. I had one serious issue with it which seemed like it was probably not of much interest for a mainstream venue. But I thought I’d point it out here.

I reviewed Jill Lepore’s book The Secret History of Wonder Woman over at the Atlantic a little bit back. I had one serious issue with it which seemed like it was probably not of much interest for a mainstream venue. But I thought I’d point it out here.

That issue is…the title, and in many ways the thesis of the book, are misleading. Lepore presents the Marston family history of polyamory, and therefore the connection between Wonder Woman creator William Marston and his lover Olive Byrne’s aunt Margaret Sanger, as unknown. If this was the first book you’d ever read about Marston and Wonder Woman, I think you’d come away with the impression that Lepore is the first one to reveal that Marston and his wife Elizabeth lived in a polyamorous relationship with another woman (Olive Byrne).

This is most obvious at the very end of the book. Lepore says, “The veil of secrecy kept by the family over Wonder Woman’s past proved impossible to lift.” She then cites writers in 1972 and 1974 who apparently didn’t know about the polyamory (Joanne Edgar and Karen Walowit.) She writes “The secrecy had consequences” and argues that there was a distortion because of this in the understanding of feminism. Margaret Sanger in the 1910s through Wonder Woman in the 1940s through WW fan Gloria Steinem in the 1970s were all connected. Because people didn’t know about the Marston/Sanger connection, they saw feminism as waves rather than as a continuous whole.

The problem with that thesis is that people have in fact known about the Marston/Sanger connection for around 15 years (or at least, that was the best guess of folks on the Comix-Scholars list serve, where these matters were recently discussed.) Marston’s polyamory was written about as early as the late 90s, and it was certainly widely known after Les Daniels wrote about it in the Complete Wonder Woman at the beginning of the 2000s. Lepore could easily have said that; Les Daniels is mentioned in her notes, and this would be the place in her narrative to acknowledge him and earlier researchers. But she doesn’t. As a result, readers are likely to believe that they’re the first ones who are learning about these “secrets.”

This isn’t to say that Lepore discovered nothing. She had access to tons of archives no one else has seen, and she has numerous jaw-dropping revelations — that the Marston polyamorous relationship appears to have included another woman (Marjorie Huntley), that Marston, Elizabeth,and Olive participated in New Age feminist sex parties, that Olive and Elizabeth were bisexual (a point that seemed fairly obvious, but has been disputed.) The book is important for anyone who cares about the early Wonder Woman, and Lepore’s work is in many regards ground-breaking. Which makes it all the more frustrating that the book’s thesis seems to rest on the revelation of the one secret Lepore didn’t discover.

As a result of this confusion, the book ends up being unnecessarily ungenerous to the numerous scholars who’ve written about the Marston Wonder Woman over the last 15 to 20 years. But more than that, I don’t think it’s ideal to frame the story of Marston and his family in terms of secrets. The closet is among other things a relationship with, or lever for, power. By urging the reader to adopt the position of the knower or the revealer, Lepore makes the story of Wonder Woman about the reader’s and the author’s rush of discovery — about the revelation of truths that the Marston family wanted to hide. The point of the story becomes not what Marston and Elizabeth and Olive made of their lives and politics and sexualities, but what secrets the book can uncover. Lepore doesn’t really contextualize that in terms of the history of gay identities or marginalized sexual identities, or of the closet; she doesn’t present the secrets as part of a history of practices that have both protected and trapped queer people, nor does she discuss Marston’s work as itself engaged with, or part of a tradition of, queer theory. I think that ends up positioning the Marstons as objectified others for the book’s readers, which again sits uneasily with the history of the closet and of the marginalization of queer people and alternative sexualities, whether lesbian or polyamorous.

Not that that’s the only takeaway from the book, certainly. And I do think Lepore is right that the history she uncovers, even if it isn’t a secret exactly, demonstrates that feminist history is more varied than people tend to think. Most obviously, the Marstons show that sex-positive and queer feminisms were around long before the third wave. Hopefully Lepore’s book will make that fact better known, and the next folks to write about Marston and his meaning can take it as more common knowledge, rather than as a revelation.

Update: Peter Sattler has a great follow-up to this post here. Jeet Heer also has a bunch of thoughtful comments below; so scroll down and then click over to Peter’s post if you want to continue the conversation (I’ve closed comments here to keep the conversation easier to follow over there.)

______

If you’re interested in reading me babble on more about Wonder Woman, I have a book coming out shortly. Lots of info and links about that here.