For those who have not yet encountered it, Saga is a science fiction fantasy series set against the backdrop of a long-running interplanetary war. The main characters, Alana and Marko, are deserters from opposing sides of the conflict who, with their daughter Hazel, find themselves pursued by bounty hunters and other interested parties. Saga is a comic about war, not only the actuality of war but the politics, and, perhaps most profoundly, the psychological and social reverberations of conflict. All of the main characters have, at some point before the story begins, witnessed and participated in acts of violence on the field of battle, and their lives have been shaped by the trauma they have lived through. This provides writer Brian K. Vaughan and artist Fiona Staples with fertile ground to approach the question of life after war. What makes their approach unusual among comic creators is their attempt to make contact with readers who are either current or former members of the military. This means that in the letter pages of Saga the rubber meets the road as it were; Vaughan and Staples attempts to depict the effects of war can be measured against the experiences of their readership.

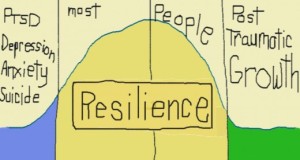

One way in which Vaughan and Staples approach the veteran is through the portrayal of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Trauma, to use Roger Luckhurst’s words, ‘issues a challenge to the capacities of narrative knowledge.’ The traumatic moment is too overwhelming to be integrated with the individual’s understanding of the world. It is thus pushed beyond the bounds of accessible knowledge and becomes, instead, a kind of ghost event which repeatedly erupts into consciousness. The U.S. Department for Veteran Affairs assert that between 11 and 20% of US soldiers to return from Iraq and Afghanistan describe symptoms consistent with PTSD. This results not only from witnessing warfare but, for 23% of women veterans, from sexual assault.

Attempts to depict trauma in literature often employ repetition, symbolism, substitution, and temporal disjunction. Comics are a particularly effective medium for describing trauma, as has been demonstrated in works such as Art Spiegelman’s In the Shadow of No Towers and Brian Bendis and Dave Finch’s Avengers: Disassembled. These comics leverage the simultaneity of the comics page, the overlapping of panels, and the capacity for the visual dimension of comics to repeat and distort images to communicate the experience of living with trauma.

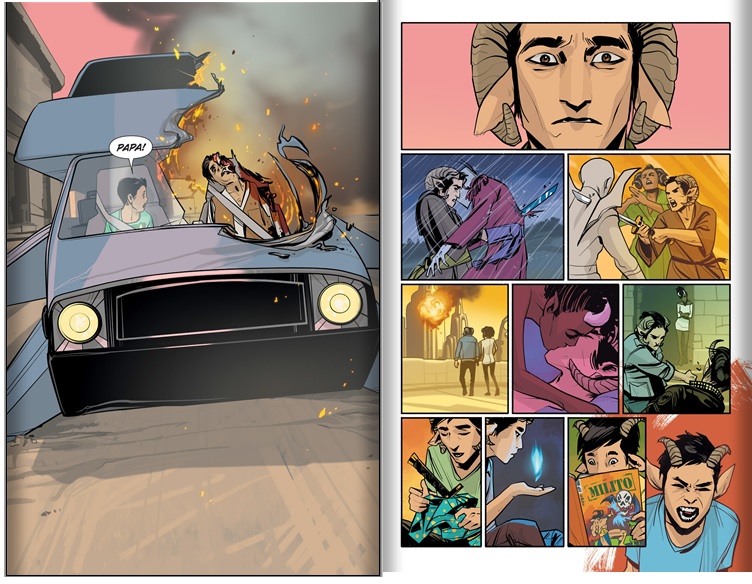

One visual exploration of trauma in Saga appears in #27 where Marko, in the grips of an ‘F-spiral’ brought on by taking a bad batch of the drug Fadeaway, recalls accidentally killing a civilian. On the following page we are taken from Marko’s face as he realises what he has done backwards in time through a series of panels, first capturing first moments of violence, then his time with his former lover Gwendolyn, to more violence, being given a sword as an adolescent, learning to create fire, reading violent comics, to, in the lower right of the page a bleed of Marko the child with his face frozen in a grimace. The background for this final image is rough brush-strokes of orange which invade the panels of the images above, creating a blood-splash that runs across these multiple time periods. There is no speech assigned to the child Marko, but the last words from the splash page before, when the son of the civilian Marko killed calls ‘PAPA!’ certainly resonate. This montage of images suggests but denies temporal order, with time periods and identities symbolically informing one another.

Marko is not the only character whose life has been shaped by trauma. Prince Robot IV’s head is a television screen which involuntarily flashes images as they enter his consciousness. Vaughan has described the TV screen as ‘a way to visualise post-traumatic stress disorder’ (The Comics Alternative Jan 19 2015). This is introduced in #1, in which the image of a severed horn flashes onto his screen to indicate both a pun on sexual dysfunction, and a literal image from the bloody conflict in which Prince Robot IV was involved. He has physically returned from war, it seems, but the violence through which he has lived has made a psychological return impossible. Later, in #2, as he questions a soldier about Alana and Marko, the image of a man engulfed in flames suddenly flashes on his screen. These images serve as a panel within the diegesis, allowing the past to visually invade the present as traumatic memories burst into consciousness. This trauma is explored more explicitly in #12, which opens with Prince Robot IV in a war zone. He witnesses a medic dying from exposure to gas. The scene ends with him covered in blood. Subsequent panels show that this scene has been playing out on his screen as he sleeps. One is reminded of Tim O’Brien’s How to Tell a True War Story in which the story of witnessing a man being killed by a landmine opens with the sentence ‘This one wakes me up’.

Vaughan also explores the social impact of war and strategies used to mitigate trauma. In #26 we learn that a would-be convenience store robber was a veteran and was carrying drugs. Marko asks why, to which he is told ‘Why would a veteran of the Wreath army be carrying Fadeaway?’ ‘Because he’s a veteran? Honestly, you’re probably one of the only vets who’s not using.’ The National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence report drug dependency among soldiers is more than double that of civilians, and that this number is rising. This is Alana’s route of escape; during the comic she becomes a habitual drug user and the theory that she does so in order to manage trauma is made explicit in #26.

The depiction of trauma within the comic has been accompanied by an attempt to engage readers who have seen conflict. As early as #4 Vaughan asked in the letters column for any readers who were members of the military to get in touch. It was not necessarily straight-forward to assume that those who have been involved in a conflict would want to read about war and its aftermath, but Vaughan’s question yielded results. In response, #6 featured a partially redacted postcard from SSG David C in Guantanamo Bay which read ‘XXXX SAGA XXXX is XXXX the XXXX best.’

#7 saw a letter from SPC Allen P. who, at the time of writing, was an intelligence analyst on active duty in Afghanistan. He wrote ‘my job is to track down insurgents to capture/kill’. He reported that he bought his comics online. The fate of Allen P became a narrative within the letter pages; in #9 Vaughan reported that the comics sent to Allen P had been returned to them and urged the writer to get in touch. Allen P wrote again when he got back to San Antonio in #11 to assure Vaughan that he is well.

#7 also featured a letter from Ogden MF Curtis, a medium machine gunner who was also in Afghanistan. He received his comics by mail – a friend bought two copies of each issue and mailed him one. #9 included a letter from Airman First Class Taylor, who was deployed in Qatar and reported that he also acquired issues digitally. In #26 a survey of Saga readers showed that many listed Iraq and Afghanistan as countries they had visited, suggesting a high number of veteran and active duty readers.

Many of these readers hint at or explicitly confirm that they struggle with trauma. In #17 Dick L. from Prescott, Arizona wrote ‘I did pretty okay in Operation Iraqi Freedom. Yeah, some guys got blown up, but I made it home in one piece … physically, at least.’ EMC Timothy Van Kleek, VSN aboard USS Elrod, whose letter appeared in #20 was more explicit:

‘I have been serving now for 15 years, and the country has been at war for most of it. I’m not on the front lines every day, but there isn’t an aspect of my life, of society as a whole, that the conflict hasn’t touched. I can feel it hanging over me constantly, like the Sword of Damocles. I may not always agree with it, and I certainly realize that what I do is a direct cause of the deaths of my fellow human beings (a fact that has caused me serious psychological trauma on more than one occasion), but I continue to do it.’

What is perhaps surprising, however, is that the aspect of Saga which seems to appeal most to readers with military backgrounds is not the depiction of trauma but the exploration of parenthood. EMC Timothy Van Kleek goes on ”Why? Many reasons. Seability. Pay. Skills training. But mostly because I have a family […] The trick, and perhaps this is why Alana is so bitter, is to not let it affect you negatively. I never tell my little girl that “I’m doing this thing I sometimes hate just to take care of you.” And I never bring my frustration or anger from work home with me.’

#7 featured a letter from Major Sam DeWind, a veteran of Iraq and an officer of 16 years service, who was, at his time of writing, based in South Korea ‘within the effective range of a couple thousand pieces of North Korean artillery’. Major DeWind’s sentiment rhymed with that of EMC Van Kleek ‘I’m really connecting with your protagonists and their struggles as parents in a perilous world […] during the periods of heightened provocations and tensions here, most notably the shelling of Yeonpeong Island in 2010, you learn something about who you are as a parent’. By contextualising war within their role as a care-giver, these veterans and active duty officers engage in what Robert Kraft calls ‘seeking the resonant influence of social support, redefining the event [and] finding meaning’. Family becomes a touch-stone, in other words, which allows them to partially mitigate the impact of trauma.

What these letters suggest is that the (albeit small) sample of veterans who read Saga not only empathise with the depiction of trauma in the comic, but that they also strongly identify with the coping methods which Vaughan and Staples portray. It is perhaps noteworthy that, while Saga engages explicitly with war and its aftermath, it does so in a fantasy setting, thereby applying a filter to war which mimics the substitution and symbolic engagement which characterizes the trauma narrative. The act of writing a letter may also employ a well-established means of addressing trauma through narrative. Saga is thus immanently relevant to a place and time when conflict damages the emotional lives of many, when men and women kill and die, and come home broken from conflicts overseas, when living with trauma is a reality for many, and the question of the place for veterans in society affects us all.