Years ago, when I was learning about cross-cultural communication and the teaching of English, a teacher of mine said that Americans are often considered very friendly by people from other countries. Sometimes, we’re considered overly friendly, overly intimate, especially when we meet someone new. Her example was something like this:

- A: How are you?

- B: Fine thanks, how are you?

- A: Pretty good. I’m actually on my way to a meeting.

- B: Oh, okay. Maybe we can have coffee later.

People who are new to English have to learn that when Americans ask ‘How are you?’ we don’t really necessarily mean it. Maybe we mean it a little bit, but not enough to hang around for an extended answer. Sometimes we are really interested in finding out, but more often than not it’s a perfunctory question and it serves as a routinized greeting rather than an earnest or sincere inquiry. (There is an enormous amount of research in discourse studies and conversation analysis about questions and answers.)

Likewise, when we answer with ‘Fine thanks,’ it’s not because everything is necessarily fine, but because it’s ordinarily expected of us. In fact, if we offer more information than that, it could be seen as inappropriate. Under some, rather restricted circumstances, if someone asks ‘How are you?’ we can answer the question honestly:

- I’ve got a stomach ache.

- My car broke down and I need a thousand dollars.

- Stan just gave his resignation to Melinda.

Usually, though, we reserve honest answers for close friends, spouses, and family members. Most often, though, the question ‘How are you?’ elicits a quick, conventional, standardized answer.

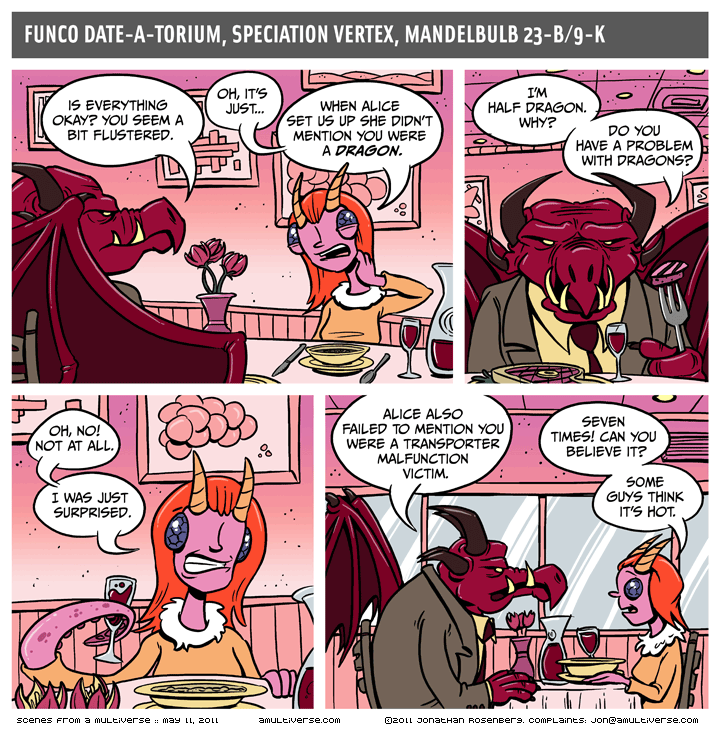

Not all question/answer adjacency pairs are routine, though. In web comics, especially those that are meant to be funny, the question/answer adjacency pair is used to further the humor of the strip. On a first date between a dragon and a transporter malfunction victim in Scenes from a Multiverse, a comic I wrote about before, questions can help uncover and solve problems or at least defuse tension:

There is a degree of similarity between Dragon’s question ‘Is everything okay?’ and ‘How are you?’ Both of them are queries about the state of the interlocutor: feelings, health, overall situation. But these two forms function very differently. In this comic, Dragon is genuinely concerned about how his interlocutor is feeling. We know this in part because of the follow-up, ‘You seem a bit flustered.’

The questions in panel 2 aren’t routine, either, especially since the two characters are out on a first date and attitudes toward dragons seem particularly germane given the situation. But in panel 4, there is another question: ‘Can you believe it?’ I don’t think this question is a routine question like ‘How are you?’ (Some people may call it a rhetorical question, popularly defined as a question that doesn’t need an answer.) This is a kind of question that is a frozen form, a formulaic utterance meant to anticipate/address an interlocutor’s question or comment about a topic or situation.

I’d like to consider question and answer adjacency pairs in two additional comics. One is from the absurdist web comic Wondermark and the other is from Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal.

The question-and-answer exchange between Batman and Alfred is funny because it so clearly violates our expectations about how the Batsignal works as a call for help. Couple that with the disagreement about computer-mediated communication and Batman’s strong opinions about how it ought to be done, and no one is surprised by the last panel. Even Alfred’s question ‘Are you mad?’ is a query about Batman’s feelings (like ‘Is everything okay?’ in Scenes from a Multiverse, above).

My last example shows how questions and answers can go a long way toward preventing clear communication. (Alfred and Batman have clear communication in the above comic, even though it may be a little bit frustrating for both of them.) This strip comes from Wondermark, and I wrote about it in an earlier post.

The question-and-answer exchange in Wondermark takes the notion to an extreme degree. The conversation starts out reasonably well, but by panel three, the interaction has gone awry. It is easy to see that the forms (the form of the questions and the form of the answers) are perfectly fine. The ‘problem’ (humor?) arises with the content of the answers. The forward motion of the conversation was strong enough to keep the exchange rolling, even if the questioner and perhaps the answerer knew that the train was going off the rails.

The forms of questions and answers in comics of course reflect to a degree our ‘real-life’ experience with them. It is the function of these adjacency pairs that provides a great deal of room for discussion. The three comics I chose are designed to be funny, and the comics artists use adjacency pairs as a linguistic component to propel the humor.

What comics have you read that called your attention to the particular forms of questions and answers?