“I don’t think I’ve ever come across anything that’s made me aware of my race,” says Kathie, a middle-aged woman from Buffalo, NY. She was interviewed in 2014 as part of the Whiteness Project, an interactive investigation of what white or partially white people think about their own race, conducted by Whitney Dow.

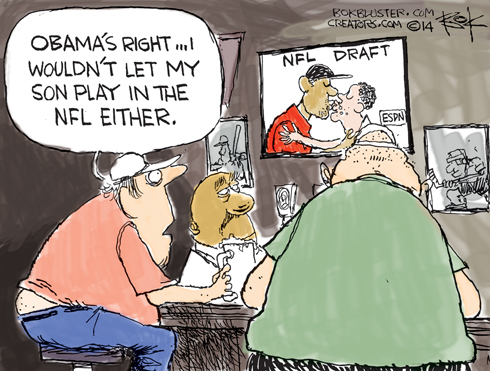

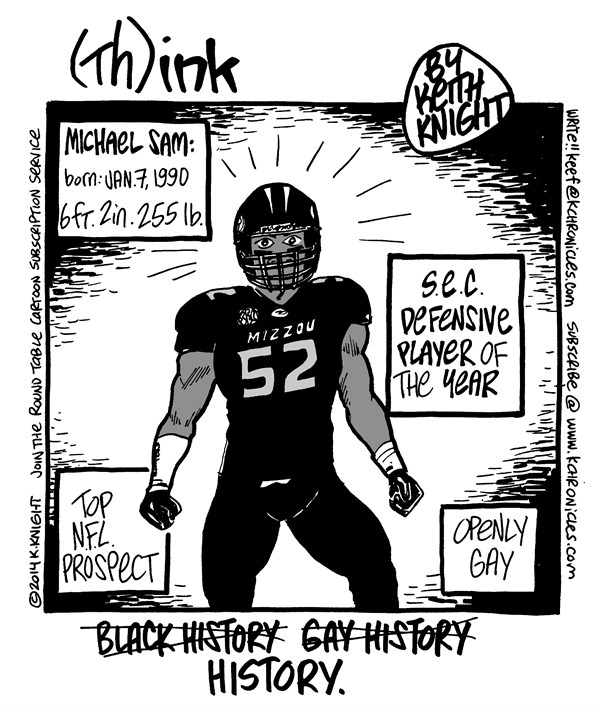

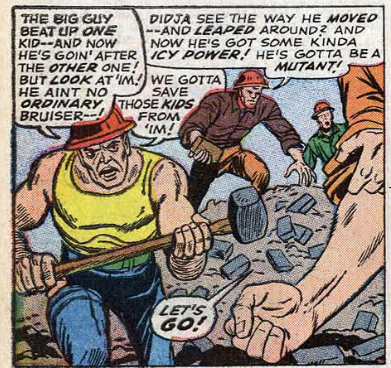

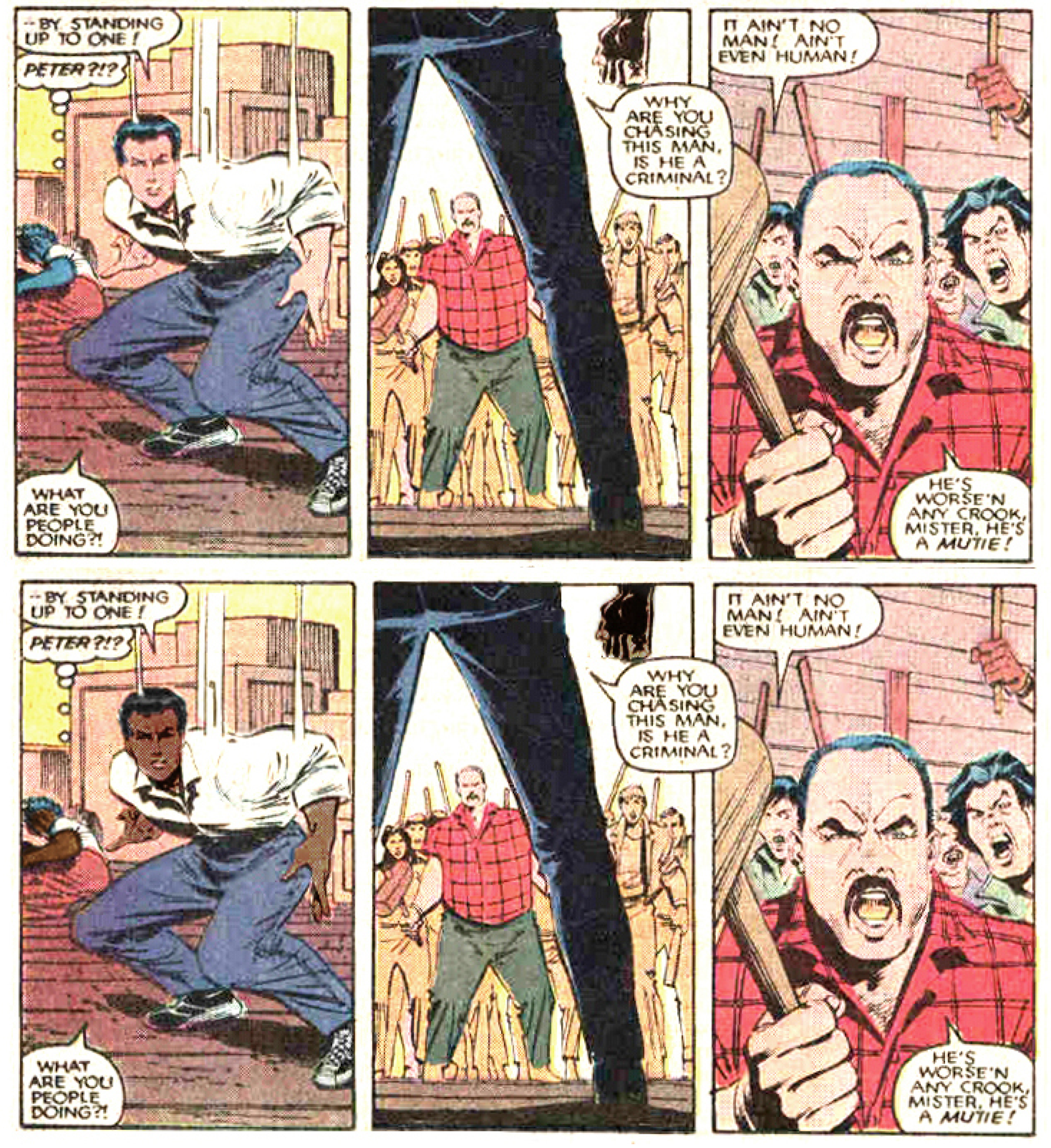

Kathie’s insistence that she doesn’t, and shouldn’t think about her race neatly underlines why the Whiteness Project is necessary and useful. For the most part, white people don’t have to confront, or address race; whiteness is unmarked and unremarked. For most purposes in popular culture Spike Lee is a black director; James Cameron is just a director. Barack Obama is a black president; George Washington, Bill Clinton, and Ronald Reagan were just presidents. Part of the magic of being white is that you’re the default, rather than the exception.

In defining white people by their whiteness, the Whiteness Project insists that whiteness isn’t normal or natural. Instead, whiteness is a specific, constructed, created identity, which white people acquiesce to, or embrace, or fidget inside of, with varying degrees of grace and insight. “So does the Whiteness Project re-center white people?” Steven W. Thrasher asked at the Guardian when the first round of interviews came out in 2014. “Yes,” he concludes, “but that’s part of the point: Dow wants his subjects to be the center of attention, and the reason for their viewers’ discomfort about white people’s views on race.”

Often, the very thing that seems to define whiteness, in fact, is the resistance to defining or seeing whiteness. In a new series of discussions with millenials in Dallas, TX, released in April 2016, the Whiteness Project interviewees repeatedly think about whiteness in terms of refusing to think about whiteness. Ari, 17, talks about how he’s stigmatized for being Jewish, and points out, perceptively, that while he doesn’t consider Judaism to be a race, other people do, which affects him. But when he talks about whiteness he insists that “the color of my skin has nothing to do with my everyday experiences”—as if his experience and those of black Jewish people would be interchangeable, or, perhaps, as if he hasn’t considered that black Jewish people exist. Sarah, 18, similarly insists, “I never think about my race…my age and my gender has a bigger influence on what I think of as my identity.” More aggressively, Leilani, 17—who is part Asian— insists, “If we want to get rid of racism, stop talking about racism.” For her, talk about whiteness is no talk; when she thinks about her white identity, she thinks about not thinking.

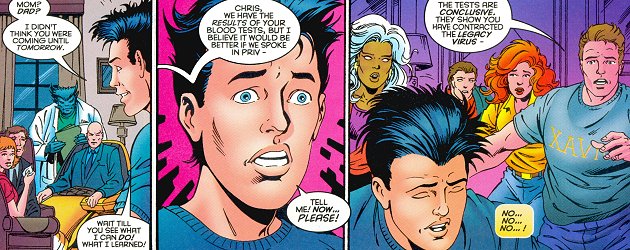

Other interviewees are more willing to try to see past whiteness’ invisibility. Lena, 21, whose father is Arab-American, talks about how she didn’t want him to come to school events because she would be teased or insulted when people realized she wasn’t white (enough.) “Being realistic, I think it’s good that I don’t look too much of anything, because just getting jobs…it’s much better for you if you look white.” Carson, 18, says, “it’s hard to know that I’ll be given more. And it makes me call into question my merit.” Connor, 24, talks about dealing drugs and notes that “there’s been plenty of times where I’ve consciously taken advantage of the fact that I was white.” He adds, ” I would be in jail if I was not white.”

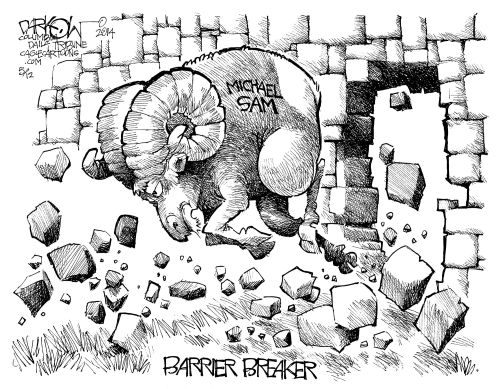

Lena, Carson, and Connor are all talking about privilege, and about the fact that whiteness is not just invisibility, but power. Invisibility and power, are in fact intertwined. You stay out of jail because you’re white, but then the whiteness becomes invisible, so suddenly you have no jail record because of personal merit, rather than because of the color of your skin. Or, as Lena says, you can get a job because your white, and then having the job on your resume is attributed to merit, rather than individual whiteness, when you go on your next job interview. In that sense, the Whiteness Project, by making whiteness more recognizable, undermines the notion that white people come by their success through personal awesomeness alone. As such, it works to confront, or destabilize, racism.

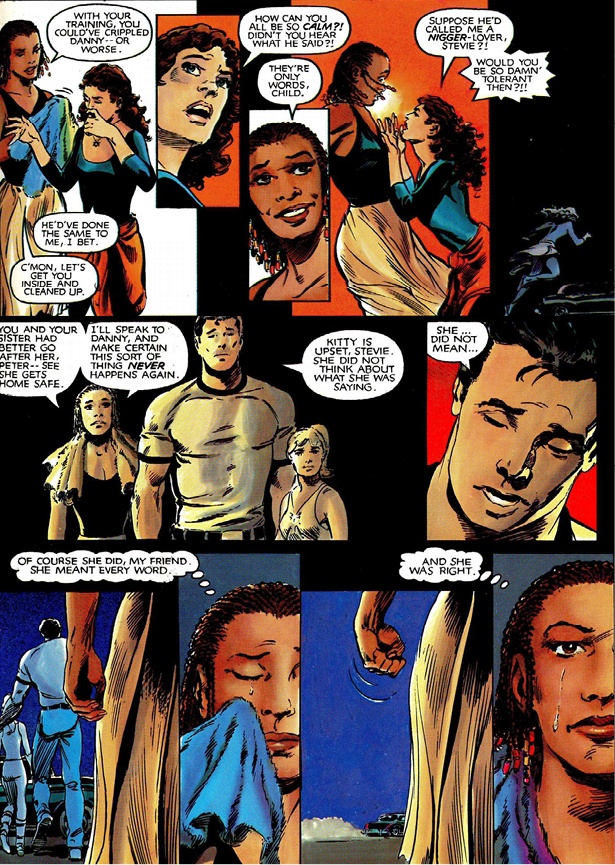

Or that would be the optimistic take. When the first batch of videos in the Whiteness Project was released, there was a certain amount of skepticism on social media from black viewers, many of whom wondered why white people needed to be given more space to talk. And some of those criticisms resonate with this second round of interviews as well. What good does it do, really, for Connor to explain that his whiteness is a get out of jail free card? To what degree is any particular anti-racist agenda advanced by listening to Chaney, 18, explain that she isn’t responsible for the history of racism and doesn’t want to pay reparations. “You can’t get things for people who are dead,” she says intensely. “It’s all in the past.” There is no more racism; there is only white people talking about their innocence, forever.

After each interview, there is a little statistic. In Chaney’s case, that statistic is that 51% of Americans think slavery is not responsible for black people having lower incomes today. The framing is particularly unhelpful; slavery happened a really long time ago, but as Ta-Nehisi Coates documents in “The Case for Reparations,” racism, and using racist laws to expropriate the wealth of black people, didn’t stop in 1865, or 1975, or with the racist subprime mortgage crisis of 2008. Reparations isn’t just about slavery; it’s about what happened in the 150 odd years since slavery, all the way up to yesterday.

“Whiteness Project aims to inspire reflection and foster discussions that ultimately lead to improved communication around issues of race and identity,” the statement of purpose on the website says. That’s a laudable goal. But framing reparations solely as an issue of slavery doesn’t improve communication around race. Instead, it makes communication around race worse. Asking white people to talk about race is useful in highlighting the importance of and power of whiteness—but it also spreads a lot of disinformation. White people, it turns out, are not all that great at talking about race, both because they lack practice, and because part of white identity is ignorance. As a result, the Whiteness Project includes a lot of white people spouting nonsense. Correcting that, or pushing the conversation to a productive place, requires more than a few statistics, especially when, on occasion, the statistics themselves are misleading.

It’s important to highlight whiteness, and to force white people to realize that white identity exists, even when (or especially when) they don’t want to think about it. As Lily Workneh says at Huffington Post, the insights here

included both unsettling and enlightening reflections” But white people becoming more self-conscious about whiteness isn’t, in itself, an assurance of progress: white supremacists and Neo-Nazis are very self-conscious about whiteness. If there’s not an explicit, and forceful, anti-racist agenda, a discussion about race can just end up rehashing prejudices. The Whiteness Project raises important issues. But ultimately, without greater critical context and engagement, racism is unlikely to be defeated, or even meaningfully addressed, by a bunch of white people talking,