Benedict Cumberbatch can’t throw a punch. At least not when he’s playing Sherlock Holmes. Khan in Star Trek into Darkness throws plenty of punches, but he’s a eugenically bred superman. Dr. Watson reports in A Study in Scarlet, Arthur Conan Doyle’s first Sherlock Holmes novel, that the “excessively lean” detective is “an expert singlestick player, boxer, and swordsman,” but we have to take his word on it.

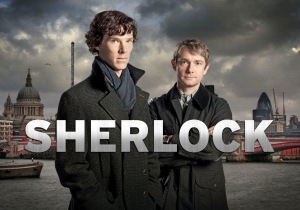

I wouldn’t know what a “singlestick” is if not for Jonny Lee Miller’s portrayal of Holmes in the aggressively updated CBS series Elementary. A singlestick, it turns out, is a stick you smack your opponent on the top of the head with. That’s what the BBC wanted to do to CBS when they heard the Americanized Holmes was premiering in 2012, because CBS had been in talks about producing a version of the BBC’s already aggressively updated Sherlock. But then the BBC would have to accept a head smack from Warner Bros. since Sherlock premiered a year after the 2009 Sherlock Holmes hit theaters.

Sherlock is the bastard brainchild of two Dr. Who writers; Elementary midwife Robert Doherty cut his teeth on Star Trek: Voyager; and the Robert Downey Jr.’s Sherlock Holmes started life as a comic book that producer Lionel Wigman penned instead of the usual spec script. When director Guy Ritchie got his hands on it, he was thinking Batman Begins. The Marvel formula was succeeding at box offices by then too, so Holmes’ superpowered intellect would have to be “as much of a curse as it was a blessing.”

A young Holmes should have nixed the forty-something Mr. Downey, but who can say no to Iron Man? Especially when Ritchie planned to restore all of Doyle’s “intense action sequences” other adaptations left out. You know, like when Holmes sneaks aboard the bad guys’ boat in “The Solution of a Remarkable Case”:

“With a lightning-like movement he seized the hand which held the knife. Then, exerting all of his great strength, he bent the captain’s wrist quickly backward. There was a snap like the breaking of a pipe-stem, and a yell of pain from the captain. Nick’s left arm shot out and his fist landed with terrific force squarely on the fellow’s nose.”

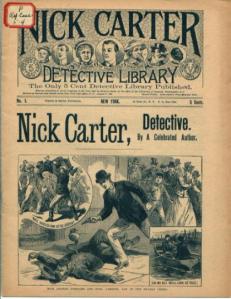

Oh no, wait. That’s not Sherlock. That’s Nick Carter. I’ve been getting them confused lately, and I’m not the only one. Carter premiered as a 13-episode serial in New York Weekly in 1886, the year before A Study in Scarlet premiered in England’s Beeton’s Christmas Annual. Carter was created by John R. Coryell and Ormond G. Smith, but Street & Smith (future publisher of the Shadow and Doc Savage) hired Frederick Van Rensselaer Dey to write over a thousand anonymous dime novels between 1891 and 1915 when Nick Carter Weekly changed to Detective Story Magazine.

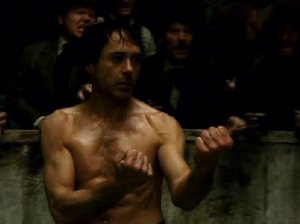

Doyle wrote a mere four novels and 56 short stories, with the rare “action sequence” lasting about a sentence: “He flew at me with a knife, and I had to grasp him twice, and got a cut over the knuckles, before I had the upper hand of him.”New York Times film reviewer A. O. Scott labels Holmes a “proto-superhero,” one who’s “never been much for physical violence,” crediting the Downey incarnation for the innovation of making the detective “a brawling, head-butting, fist-in-the-gut, knee-in-the-groin action hero” (what one commenter called “The precise opposite of Sherlock Holmes”). The film opens with Downey in a bare-knuckled boxing match, displaying the skills Doyle only hints at. Apparently Holmes once went three rounds with a prize-fighter who tells him, “Ah, you’re one that has wasted your gifts, you have! You might have aimed high, if you had joined the fancy.”

Nick Carter, on the other hand, has the fancy: “He bounded forward and seized in an iron grasp the man whom he had just struck. Then, raising him from the floor as though he were a babe, the detective hurled him bodily, straight at the now advancing men.” Yes, in addition to all of Holmes’ sleuthing powers, Carter has superhuman strength. And a bit of a temper—the secret ingredient American producers feel is missing from all those stodgy British incarnations.

Jonny Lee Miller’s Holmes doesn’t hurl men like babes, but he has broken a finger or two sucker punching serial killers. The leap over the Atlantic has made the Elementary detective’s passions more violent than his London predecessors. He also has a tendency to wander onto screen shirtless, displaying tattoos and a well-curated physique. His drug problems seems to be a carry-over from his Trainspotting days, which means the English accent is as authentic as Cumberbatch’s. In fact, Miller and his BBC counterpart co-starred in a London production of Frankenstein in 2011. You’ll never guess who played the doctor and who the monster. Literally, you’ll never guess—because Miller and Cumberbatch swapped parts nightly. Mr. Downey was busy completing the sequel Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows, and so was not available for matinees.

Plans for a Sherlock Holmes 3 have been in talks too, but Downey was busy with Avengers, Iron Man 3 and now Avengers 2. Why settle for a proto-superhero when you can play a real one? At least the long-delayed season 3 of Sherlock finally arrived. It was perfectly fun watching a barefoot and CGI-shrunken Martin Freeman chat with Cumberbatch’s growly dragon in Hobbit 2, but nothing beats the Holmes-Watson bromance—a delight the otherwise delightful Jude Law and Lucy Liu can’t quite deliver with their Frankenstein partners. Sherlock is also the last show my family still watches as a family, so I don’t mind the BBC cauterizing the Nick Carterization of the character.

Of course Nick has evolved since the 19th century too: a 30s pulp run, a 40s radio show, a 60s book series. I have the anonymously written Nick Carter: The Redolmo Affair on my shelf. It’s a musty James Bond knock-off I found in a vacation house and kept in exchange for whatever I was reading at the time. I can’t bring myself to flip more than a few pages: “I streamrollered my shoulder into his gut and sent us both crashing to the deck. I got my hands on his throat and started squeezing. His fist was smashing down on my head, hammering into my skull.”

In Nick’s defense, Doyle considered Sherlock Holmes schlock too. He hurled him over a cliff so he could stop writing his character—but the detective keeps bouncing back. Elementary is certain to be renewed for a third season, and the Sherlock season 3 finale is a cliffhanger with the next two seasons already plotted. The biggest mystery is how they’ll keep Cumberbatch out of a boxing ring.