In 2006, four-year-old Sean Paddock suffocated in a blanket his mother tied too tightly to stop him from getting out of bed. She’s now serving a life sentence for felony child abuse and first-degree murder. She was a follower of Michael Pearl’s parenting manual To Train Up a Child, which warns never to put a child “down and then allow him to get up…. To get up is to be on the firing line and get switched back down.”

In 2010, seven-year-old Lydia Schatz died after being beaten with a plumbing tube. Her father is serving a minimum of 22 years for second degree murder and torture, her mother 13 for voluntary manslaughter and unlawful corporal punishment. They were following Michael Pearl’s advice: “a plumber’s supply line is a good spanking tool. You can get it at Wal-Mart or any hardware store. Ask for a plastic, ¼ inch, supply line. They come in different lengths and several colors; so you can have a designer rod to your own taste.”

In 2011, 13-year-old Hana Grace-Rose Williams died of malnutrition and hypothermia in her backyard. Her father received 28 years in prison, her mother 37. What do you call these people? Michael Pearl, a fundamentalist pastor and founder of the non-profit organization No Greater Joy, says they are good, Christian parents. “Prove that you are bigger, tougher,” teaches Pearl. “Defeat him totally.”

Frank Miller calls these people “Batman.”

Miller and artist Jim Lee stirred up DC in 2005 with their All Star Batman and Robin and its portrayal of a Pearl-style Bruce Wayne abusing his own adopted child. According to a Sheriff’s report, the Williams deprived their adoptive daughter “of food for days at a time and had made her sleep in a cold barn.” Batman keeps Robin in an empty cave and tells him to catch rats if he’s hungry. If he cries, he gets slapped. When Alfred interferes by supplying the twelve-year-old with a blanket and an order of fast food, Batman threatens his butler physically.

Pearl would approve. “It has come to my attention,” writes the evangelist, “that a vocal few are decrying our sensible application of the Biblical rod in training up our children. I laugh at my caustic critics, for our properly spanked and trained children grow to maturity in great peace and love.”And sure enough, Batman’s tough love program quickly transforms Dick Grayson from a whimpering orphan to a power-punching Batman Jr.

Miller is an evangelist too. His God is the Manichean kind of absolute good vs. evil, the one little Bruce Wayne prayed to when he swore “by the spirits of my dead parents to avenge their deaths by spending the rest of my life warring on all criminals.” Miller expanded that dark vision to new depths in the early 90’s with Sin City—while Pearl was self-publishing his parenting manual. The D.A. who prosecuted the Shatz case called To Train Up A Child “truly an evil book.”

In 2009, while the Schatzes were still beating their children with plastic tubing, Pearl was applying his comic book vision of good and evil to an actual comic book titled Good and Evil. He advertises his Bible adaptation as “The Ultimate Superhero Graphic Novel!” and explains that he didn’t want “typical religious art” but “the traditional comic look that is so familiar all over the world.” It’s drawn by Danny Bulanadi, a former Marvel and DC artist whose 1979 Man-Thing is in my attic box of childhood comics. His 80s and 90s credits include Conan, Captain America, Blue Beetle, Hulk, Indiana Jones, Fantastic Four, and The Micronauts. After becoming a born again Christian, Bulanadi, according to the introduction, “was not comfortable with the work he was doing and so quit.” I’m not sure what exactly he was uncomfortable with, since Good and Evil encapsulates the same comic book values as most other superhero stories.

Pearl says it’s “impossible to cover the entire Bible,” so he selects “just that Old Testament background that is pertinent”—which apparently means adding a few supervillain scenes. “The Bible,” according to Pearl, “tells us God created numerous kinds of angelic beings to offer praise around his throne, but one called Lucifer led a third of them in rebellion.” Tales of rebellious angels don’t appear till the Book of Isaiah, yet Pearl needs us to know about them on page one. “But,” he adds, “this is not their story.”

Except it kinda is. We haven’t gotten through the first week of creation before Bulanadi’s sketching evil eyes peering from the blackness of his panels. “On the sixth day,” Pearl declares, “with the evil ones watching, God formed a new creature from the dust of the ground.” They’re there again a page later as God is forming Eve: “Satan, the Evil One, watched.” Two more panels and Bulanadi is drawing a bipedal lizard monster that would look at home in Tales to Astonish: “Satan hated God and wanted to destroy what God was doing, but he needed a way to communicate with Eve, so he entered the body of a beautiful creature and spoke through its mouth.” Pearl and Bulandi disagree about the adjective “beautiful,” but, more importantly, Pearl disagrees with God. According to Genesis 3:1, “the serpent was more crafty than any other beast of the field that the Lord God had made”—Lucifer isn’t a “beast of the field,” and there’s nothing in the Bible suggesting he “entered” it. But Pearl loves to play up God’s arch-nemesis. “Here is promise of a future battle,” he tells us, as Bulanadi’s lizard monster morphs into a snake. Pearl, like most comic book writers, just wants more fight scenes.

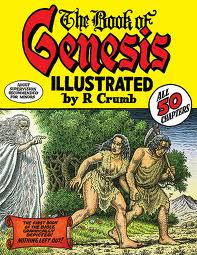

If you’re looking for a faithful adaptation, I suggest Robert Crumb’s The Book of Genesis Illustrated. If you’re also familiar with Crumb’s Bible of Filth (it includes the outrageously incestuous “A Family that LAYS Together STAYS Together”), you’ll assume he’s out to lampoon Christianity again. The prominent cover warning, “Adult Supervision Recommended for Minors,” doesn’t help. But you’d be wrong. Crumb’s drawings are respectful. Yes, he, unlike Bulanadi, forgoes conveniently angled vegetation, so there are plenty of full-frontals of Adam and Eve in the Garden, but no sex, just a little cuddling, all of it in God’s benevolent presence.

God’s long beard and robe are a cliché, but they bring out the odd thing about Bulanadi’s God. He’s invisible. The tails of his squiggly talk bubbles point at nothing. When he “formed a new creature from the dust of the ground,” Bulanadi draws the dust forming itself. When “God breathed his own life into the body of clay,” Bulanadi’s glowing cyclone of holy oxygen swirls from off-panel. But Crumb places God front and center, getting his hands dirty and embracing Adam as he exhales into his nostrils.

Crumb also includes all of God’s words. “Every other comic book version of the Bible I’ve seen,” he writes, “contains passages of completely made-up narratives and dialogue, in an attempt to streamline and ‘modernize’ the old scriptures, and still, these various comic book Bibles all claim to adhere to the belief that the Bible is ‘the Word of God,” or “Inspired by God,” whereas I, ironically, do NOT….” Sure enough, go to the No Great Joy website and you’ll learn that “the sixty-six books of the King James Version, nothing added or deleted, constitute the whole of Scripture ‘given by inspiration of God’ to English speaking people.” Crumb uses the King James too, but unlike Pearl, he includes “every word of the original text.”

Pearl’s selectiveness privileges some ideas over others. His Genesis keeps repeating “obey” and “rebellion,” the same words he emphasizes to such destructive ends in To Train Up A Child. His comic book God demands absolute obedience, and so the obedient Pearl demands absolute obedience from children. Part of a child’s training, explains Pearl, “is to come submissively. However, if you are just beginning to institute training on an already rebellious child . . . then use whatever force is necessary to bring him to bay.” And this is justified because Adam’s “willful and direct disobedience to God resulted in legal estrangement from God and precipitated the curse of death on Adam and all his descendants.”

But don’t worry—a diet of beatings and cave vermin can fix that. Alfred may disagree, refusing to be Batman’s “slave,” but Robin gets with the righteous program. When you live in a comic book world of Good and Evil, choices are easy. Robin’s adoptive father, like Pearl, is a divinely pledged instrument of absolutism. And, hey, who doesn’t want to be Batman?