Wine is a great accouterment for villains. Aristocratic and impenetrable, a glass of red can suggest that its drinker lounges about, sipping the blood of his enemies and chuckling evilly from the shadows. White wines code the airy disconnect of the elite, aestheticized and cruelly indifferent of everyman struggles. Hannibal drinks Chianti and eats people, and the merciless denizens of Elysium drink whites at garden parties in space. Wine conveys authority, but it’s a fairly obvious power-play. And a better villain can out-power that power-play. Enter Clarence Boddicker.

Wine is a great accouterment for villains. Aristocratic and impenetrable, a glass of red can suggest that its drinker lounges about, sipping the blood of his enemies and chuckling evilly from the shadows. White wines code the airy disconnect of the elite, aestheticized and cruelly indifferent of everyman struggles. Hannibal drinks Chianti and eats people, and the merciless denizens of Elysium drink whites at garden parties in space. Wine conveys authority, but it’s a fairly obvious power-play. And a better villain can out-power that power-play. Enter Clarence Boddicker.

Kurtwood Smith’s performance in the original Robocop is one of a kind. Boddicker’s smile is vicious, but disturbingly sweet. One moment he squirms with glee, only to be still and deadly the next. He’s the ringleader of a hysterical, trigger-happy gang, which more than anything resembles a group of bros gone wrong. Which is a great reminder for the goonish underbelly of many male-bonding narratives.

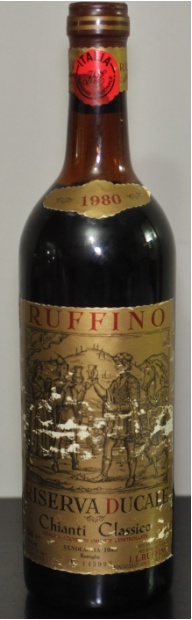

But Boddicker doesn’t dominate as much as destabilize. He’s balding and bespectacled, yet emotes childishly. He throws tantrums. He unpins a grenade with his tongue, peering down at his quarry with an odd, come-hither look in his eyes, practically miming to his employer’s recorded assassination statement. Boddicker’s interaction with the one glass of wine in the film is no less subversive. When demanding a cut in the price of cocaine, Boddicker sticks two of his fingers into a drug lord’s glass of Ruffino Riserva Ducale, and then snorts the drops from his fingers. Even better, the drug lord then picks up the glass, and in a bizarre act of social facilitation, takes a sip.

It’s interesting that the wine appears here, in a cocaine factory, and not in the hands of one of the privileged board members of the evil corporation OCP. While it would have been ridiculous for wine to be served at their meetings, its equally absurd for it to appear in Sal’s rock shop. Not to mention that Ruffino Riserva Ducale is prestigious. Karen McNeil deems it a ‘must’ to try in The Wine Bible, “One of the leading producers of traditional Chianti… its Ruffino’s Chianti Claissico riserva called Riserva Ducale that is the jewel in the crown.” Sal’s bottle looks to be contemporary to the ‘80s; a current vintage Riserva Ducale would cost about $25 retail, and about $50 or more in a restaurant. Not a rare or overly expensive wine, but not cheap either, and Sal seems to be drinking it casually. Which is a power statement in itself—Ruffino Riserva Ducale is his house wine, even when it can be barely tasted over the wafting powder. Drinking Ducale in a cocaine factory reduces the wine to an empty signifier of prowess and sophistication. Snorting it is a more honest admission of what it is—a power trip.

Ruffino Riserva Ducale Vinages: 2001 (Standard label), 1953 (Standard label), 1980 (Gold label)…The packaging in the still is definitely from the 80s.

A quick dip into the history of Chianti reveals a stranger layer at play. Up until the seventies, Americans knew Chianti as a cheap, barely palatable wine in a straw bottle. While Chianti must be primarily made with the black grape Sangiovese, misguided Tuscan wine laws permitted—then required– the inclusion of Trebbiano and Malvasia into the blend, which are (usually) characterless white grape varietals that are easy to grow. This stretched the Sangiovese a little further, but watered down the quality significantly. While there had always been a tradition of making Chiantis for cellaring, like Riserva Ducale, their reputation was harnessed to the low esteem for the basic Chiantis.

In the early seventies, Ruffino was one of the first producers to do away with the straw bottle, and presumably decrease the amount of white grapes in the mix. Other producers created “super-Tuscans,” highly lauded, heavy-weight Cabernet Sauvignon blends that often, but not always, included Sangiovese. As these didn’t conform to existing wine laws, they couldn’t be labeled Chianti, and their popularity mirrored the success of the renegade wineries in Napa, California. In order to compete with these non-Chiantis, a “Chianti Classico” designation was created in 1984, which required 80% or more of the blend to be Sangiovese, harvested from only the most traditional growing areas, and the final 20% comprised of black grapes like Cabernet, Merlot, Canaiolo or Colorino. However, the use of white grapes wasn’t completely outlawed until 2006.

Chianti’s reputation progressed enough for Hannibal to name-drop it in Silence of the Lambs in 1991. Parallel movements occurred at the same time in Piemonte, with Barolo and Barbaresco, and throughout the whole of Italy by the late 80s. Italy attracted the attention of American wine critics and their high scores—and a preference for large, fruity wines. For better or for worse, Italian wines changed to fit American palates. In turn, America replaced fantasies of France with rustic Italy, for a variety of reasons ranging between changing kitchen habits and Reaganism. As covered by Lawrence Osborne, in The Accidental Connoisseur,

“Unlike the French, Italians were spontaneous, unsnooty, casual, unpretentiously friendly, and family-oriented—that is, much more like Americans themselves….The huge success of Italian-sounding wines like Gallo and Mondavi had much to do with this commercialized idea of Italy: the Italian family seated around the Mediterranean banquets in golden sunshine. Somehow Italy… had the innocent energy of nature. Like fruit-and-veggie-packed wine itself, that sun-kissed land had about it a whiff of the health food store.”

Meanwhile, Mayor Giuliani was patching broken windows and gentrifying Manhattan, with its heavily Italian heritage, into a safe haven for the wealthy. Film experienced the renaissance of the Italian mob-boss, who took hold of the American imagination with Coppola’s The Godfather in 1972, and was a mainstay by Scorsese’s Goodfellas in 1990, about the time Italian wines went from plonk to paragon.

Sal, wine glass in hand, registers this transformation. Authoritative, barely accented and dressed in a khaki suit, Sal is the image of late-eighties self-indulgence. He barely registers as a bad guy in comparison with Boddicker, who derisively calls him a ‘wop.’ Sal is the image of elevated crime, with a mob pedigree, which he signals not with course stereotypes, but with his enlightened, Italian wine habits. Boddicker’s gesture calls his bluff, replying that crime is always a kind of perversity. By not relying on racial signfiers, and instead including this vinous conceit, Verhoeven can satirize mob movies, and the thuggish indulgence of Reaganism and the eighties, while avoiding actual racism against Italians.

Boddicker might be crazy, but he’s honest about who he is. Robocop attests that crime is chaos, twenty years before The Joker’s declares this in The Dark Knight. Boddicker and the titular Robocop oppose each other like order and anarchy, yet they exist on the same ethical axis, and importantly, are both revealed to be corporate puppets in the end. Sal floats off in cloud-cuckoo land, where there’s honor amongst thieves, or at least a hierarchy. Unfortunately for him, Robocop guns criminals down rather indiscriminately.

This post is the second in a continuing column, What Were They Drinking?!, featured on The Nightly Glass, and occasionally co-posted here on The Hooded Utilitarian.