I love roleplaying. There’s something very liberating about indulging in some mild escapism by jumping into the heart of another person to briefly write another life. It’s nestled somewhere between playing pretend, improvisational theatre, and gaming. I’d like to briefly explain how the mechanical framework for these games shape the stories they produce, specifically by contrasting free-form, chat-based play versus the more common tabletop varieties. When I was a teenager and younger adult, I roleplayed away a huge chunk of my free time in graphical MUDs (Multi-User Domains) like Furcadia or on internet relay chat groups. Eagerly looking for new experiences, I dipped in and out of tabletop roleplaying groups, but I was taken aback at how different the focus was. It wasn’t the mechanical underpinnings that pushed me away, it was how my previous stories about romance, poverty, family life, and skullduggery got replaced with punching goblins in the face. At the time I wrote it off as differing tastes, but now I understand that these characters and players were really just reconfiguring to fit into the mechanical systems of interest.

To give you an idea, my previous experience is generally classed as a variety of free-form roleplay, where players write segments either in real time or via a bulletin board, and players accept that the post exists within that fiction or is unacceptable and rejected. So the narrative that takes shape is a consensus one, and its incentive structure resembles the shape of a continually iterating Coordination Game…of sorts. A player may, in a vacuum, accept or reject any given segment unilaterally (or with agreement from others), but their positive cooperation and investment in the stories both by being accepting and presenting material that is interesting will likely please their partner and make their own segments more likely to be accepted.

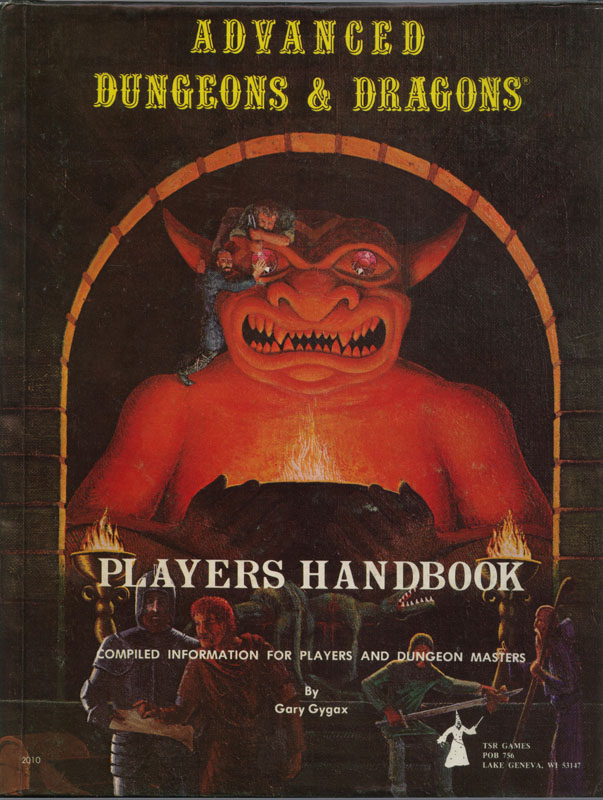

All sorts of different incentives and relationships grow out of that game theory soil like a particularly stubborn weed. Generally it’s easier to be passive and get to know other players’ characters than it is to punch them in the mouth and take their things. In most tabletops, however, violence has a consistently predictable quality. People and creatures are rendered into numbers that quantify if one could or could not “take that guy”, and that psychic comfort of knowing “what should happen” pulls on motivations and incentivizes play towards Conan the Barbarian instead of Spice and Wolf.

The end result is that free-form stories are usually based on continued relationships, positive and negative, rather than overt violence. More interestingly, the interaction between characters and material things takes something of a weird left turn. There’s no reason why a player cannot be a king, a dock worker, a powerful demon, a serf; the system of consent dictates a player’s role in the community, so the traditional arc of accumulation of gold, experience, accolades, simply evaporates. The things that a character acquires or possesses are not about what they can let the player do anymore; they’re about what they mean to the character, the story, and the setting. It’s not: “What can this thing I’ve acquired allow me to fantasize?”, but instead: “What are the things worth fantasizing about?”

It gets more complicated, however, because unlike a tabletop, an online space can be subdivided with incredible ease, so what before would be three to five people cloistered around a single series of events, you now have tens of people bouncing against each other, with their own personal stories that intersect in these different spaces. Characters and players traverse room after room in a shared setting just as they would space, situating personal events in a perpetually changing context that’s unique to the perspective of each individual player. In a graphical MUD like Furcadia, the segmentation of space becomes an even finer gradient, as rooms are no longer discrete, and are maps instead, where one can only “hear”, or see posts from characters from the screen they currently inhabit. The twists and turns of a brief encounter aren’t from a humorous critical failure or heroic critical success, but from the strange misfortune of bumping into your worst enemy in a large, shared space where one was never guaranteed to cross paths ever again.

Serendipity is alive and well without dice in these systems, but the tensions surrounding fate are very different. When one plays with a more traditional game, the Dungeon/Game Master is constantly walking a thin line: making a more or less unilateral decision whether or not a rule or roll is going to be followed, in the interest of story-telling. In a free-form setting, there’s all sorts of crosswise motivations, the plot of a character, the immediate respect of your peers, the maintenance of a firmer canon, and so on. This reflexive, continual criticism and investigation means that players have to respect each other and their stories in order to continue or else be pushed out via slowly increasing social tension. When a player or DM gets out of hand at a tabletop, the entire campaign can simply explode, but a problematic player in a free-form group could be squeezed out to different areas to avoid certain players/characters/scenarios, or could be pushed out of the shared area altogether without so much as causing a wrinkle in the shared continuity.

In many ways my fundamental criticisms of mainstream roleplaying are essentially the same that I have for mainstream gaming: I think these games are a regurgitation of Capitalist ideology, and squeeze characters and stories through an arc of accumulation, and violent conflict when none of those qualities are a necessary element of character or story in other contexts. They have antagonism and violence as a fundamental assumption, and often enjoying them means an additional layer of strange, hierarchical consent above and beyond a mere suspension of disbelief. I did a quick summary of the characters I played over the past seven or so years, and I’m really unsure if their central dramatic conceits could exist in normal roleplaying frameworks, or would be improved by layering the core assumptions of tabletop roleplaying games on top of them.

Characterizing tabletops as only about slaying beasts and free-form to be heartfelt stories is disingenuous however, if only because I have skewed the data for my argument, which I will now rectify. Those involved in fantasy and sci-fi are probably well aware of Sturgeon’s law: “Using the same standards that categorize 90% of science fiction as trash, crud, or crap, it can be argued that 90% of film, literature, consumer goods, etc. is crap. In other words, the claim (or fact) that 90% of science fiction is crap is ultimately uninformative, because science fiction conforms to the same trends of quality as all other art forms” As an addendum to this law, I’d like to posit that the constraints of any given genre or form have the most profound effect on the crap that forms the 90%. So it follows that since tabletops have violence and Capitalism baked in, and reproduce it, what kind of crap does free-form play generate?

The bottom of free-form play is a crust of barely literate, adolescent sex romps, to the point where some roleplaying services like F-List allow players to list their preferred sexual activities, and at the time of writing, only about 10% of its user base lingers in its non-sexual oriented areas. In an ideal world, free-form is an excellent vector for adult entertainment, but given the quality of both a lot of play being undertaken and the occasionally poisonous communities that exist…It ain’t perfect. Because space, sessions, and conversations can be so readily subdivided into every more private segments, these spaces breed play and players into remarkably unfiltered, queer dreamers.

At the outermost reaches of these spaces, the cis het male of mainstream media begins to look foreign and alien in an endless stream of octuple titted furries, Eldritch sex horrors, and confused Sonic remixes looking for edgeplay or fantastic scenarios of partners being swallowed whole by a urethra of a double-dicked Moloch. This regurgitation of pop culture mixed with the unfiltered sexual id of young adults could not exist nearly as easily in any other space, especially not in tabletop settings where one either needs to find or create rules to describe and constrain these characters and topics. In a free-form space, the only real barrier to finding the double-dicked Moloch of your dreams is to find another player who shares that particular kink.

This is the inevitable product of players exploring themselves and their desires in areas that are as public or private as they wish, and are respectfully constrained by their consent and the consent of their partners/other players. Through different forms, you see different faces of the same culture, and if one were to ask me what I saw in others through free-form roleplay, I’d say I saw a bunch of lonely perverts and socially maladjusted weirdos thirsty for physical and emotional connections, whether a simple hookup, or a shared dream that spanned years of time.

Free-form play naturally creates romances and intrigues while attracting the queer and the perverse specifically because of the mechanical vacuum that exists in that play style. The identities of characters, their desires, and their actions don’t have to be explained by a set of rules, and then mediated by a judge, so they spring outwards into all sorts of strange shapes to fill that void. It isn’t that any of these things couldn’t necessarily exist in a normative tabletop setup, it’s that the levers of power and of certainty, the things that players normally gravitate towards, are ineffectual in describing and mediating social interactions and identities. These mechanical levers, however, are astoundingly effective at describing violence and material accumulation in great detail, and bend players and their motivations towards those things as an end. It’s because of these distinctions in form that two different styles, sharing the same goal of fantasy escapism, can nevertheless create very different stories for very different people.