The index to the Comics and Music roundtable is here.

_____________________

Charles Schulz famously loved drawing (or writing?) musical notation. Schroeder was always playing “real” measures of Beethoven in the strips.

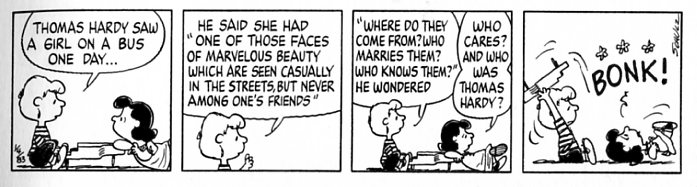

In part, the notes are there simply as a design element, the same way Schulz draws lots of inky slashes of rain. They’re intricate and pretty and fun to look at; they add visual interest. Often, though, the notes also become a visual joke; their presence as design or as visual is incorporated into the visual narrative. So, above, the notes dangling over Lucy hang over her like an oppressive cloud.

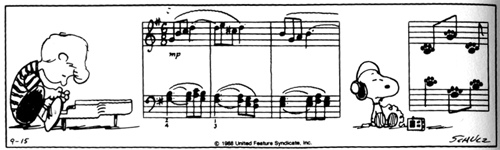

In this image, the joke is even simpler. It’s a visual pun that barely rises to narrative — though the subtext (that pop music is paw music for dogs) is cute.

Part of the point for Schulz is surely the simple virtuosity of the drawing. Schroeder wowing the girls here can’t be that far removed from Schulz wowing his audience; another reminder, perhaps, that Charlie Brown is not necessarily, and often not really much at all, the Schulz analog in the comic. This gag can be seen as a kind of extension of this one — both play with the gendered potency of high art virtuosity. That look Violet gives Schroeder at the end has maybe more intent behind it than is entirely comfortable in a six year old.

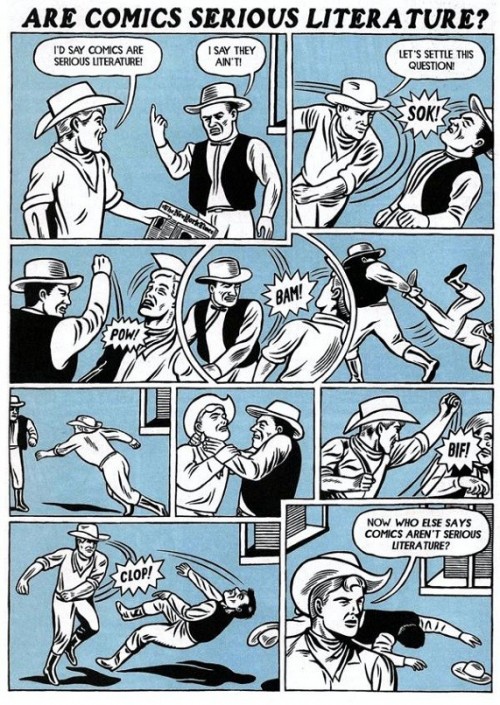

If the musical notation is a metonymy for high art, to be contrasted, in many cases, with low art insufficiency, then that high-art signalling functions in various ways.

On the one hand, Schulz, as I said, is the high art creator — he’s the one making the notes, after all. On the other hand, though, the high art gets contrasted with the low art of the comics strip — Snoopy’s paw music, or Charlie Brown (the older boy) still plinking away at kids’ stuff, as all those younger high artists pass him by. In this sense, Schulz again collapses into Charlie Brown — locked out of high art virtuosity and romantic opportunities, disappointed in art as in love.

Another reading, though, might be to see the use of musical notation not as a way to contrast high and low art, but rather as a way to show their similarities. Musical notes, like comics, are pictures that carry a message. They are images you read — as made especially clear in Linus’ whistled stanzas, where speech bubble and notation are literally fused into one. High and low art, music and comics, function as sequences of images, running in parallel across the page.

Those parallel messages, though, are different from each other in at least one important way for me, as a particular reader. I can read the comics; I can’t read musical notation. With comics, you have the ease of pictograms; with musical notation you are confronted with a code requiring specialized knowledge, which either shuts you out or ushers you into the inner circle with Schroeder.

Again, you could see this as a high-art/low-art distinction — though, after all, the high art isn’t outside low art, but in it. Schulz has, perhaps, found a way to invert Lichtenstein. Instead of low art providing content and energy and accessibility by being incorporated into high art, high art provides content and energy and, perhaps, validation, by being incorporated into low art. Beethoven’s the inverted pop in Peanuts for those who can hear it…and maybe even more for those who cannot.