Femininity is not frequently accorded respect. In gay culture, “femme” is still rarely an option associated with strength, meaning, knowledge, and freedom. At best, girliness may have a temporary strategic appeal, but it can’t be dissociated from values of impotence, consumption, and passivity, articulating itself only through cruel gossip and tacky melodrama. This may explain partly why the hyperfeminized scenes and characters of Japanese comics (manga) for adolescent girls (shojo) has had so little appeal to American fans of superhero comics, fine art, literary fiction, or their collective unholy offspring, alternative comics. And yet I insist that the art now on display in the group survey show Shojo Manga! Girl Power! at Columbia College’s modest C33 Gallery, is more worthwhile, on the whole, than the work on display in Los Angeles in the all-star Masters of American Comics show, soon to be coming to the Milwaukee Art Museum. The reason I find a collection of work by Japanese masters like Osamu Tezuka, Ryoko Ikeda, Moto Hagio, Masako Watanbe, and the female art and writing collective CLAMP so important is not only because the shojo manga form will continue to gain in influence in the U.S., but because it shows possibilities for comics that have been largely untested by Western creators.

Despite the show’s celebratory title, I would hardly make a claim that, if any form of pulpy pop culture is going to set young women free, shojo manga will be that emancipatory force. On the other hand, shojo manga exemplifies many of the seeming contradictions I often find moving in Japanese visual art. The page layout is utterly unlike the traditional ice-cube tray format of American comics, merging the elegant, startling shapes and juxtapositions of Russian Constructivism with the Eurotrash hair-model illustrations of Patrick Nagel and the enormous sparkling eyes of scruffy soulful orphans in thrift-store paintings. This sense of giddy, helium-sucking boundlessness applies generally to the storytelling in shojo manga as well. Distinctions blur between inner and outer states, waking and dreaming, past and future, male and female, gay and straight. Identities and realities swim in a candy-coated vision of romantic glory that, despite the petty objections of sundry aesthetes, hardly qualifies as disposable or superficial, particularly in comparison with the cartoony but macho post-Pop skater and graffiti art that has received undue respect in the art world for far too long.

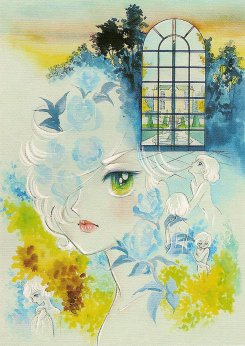

From Amaterasu,©Suzue Miuchi

From Poem of Wind and Trees,©Keiko Takemiya

Writers in the two sources I consulted, the Shojo Manga! Girl Power! catalog and the July 2005 edition of The Comics Journal, which was devoted exclusively to shojo manga, obsessively reiterate the immense popularity of the medium, both in the U.S. and east Asia. In Japan, comics conventions peopled almost entirely by women (as yet unheard of here), most of whom are allowed and encouraged to self-publish and sell their fan fiction (ditto), can pack in upwards of 500,000 attendees. In the U.S., the market for manga has recently topped $100 million yearly, the majority of those sales going to shojo manga titles, presumably being bought mostly by teen and pre-teen girls. As I’ve intimated, though, the content of shojo manga is what makes it extraordinary. Themes of abuse, suicide, sex, and changing family structures are dealt with in operatic and soap-operatic style. But perhaps the most provocative aspect is the resounding success of comics for girls that deal with homosexuality and highly unstable gender roles. Beginning with the unchallenged master of the media of manga and anime (animation), Osamu Tezuka, the 1953-56 story Ribbon no Kishi (The Knight of the Ribbon, or Princess Knight), featured the princess Sapphire, who carries within her the heart of a man and the heart of a woman. She is prevented from ascending the throne as a woman, and is raised as a boy, but then falls in love with a prince from a neighboring kingdom, and so re-feminizes herself with a flowing, flaxen-haired wig. Another major series, Ryoko Ikeda’s The Rose of Versailles (1972-73), focuses on Oscar, the daughter of a noble family who is raised as a boy and serves as a military commander under Marie Antoinette, falling in love with Andre, the son of her wet nurse. But cross-dressing suggestiveness, while its popularity endures, has since expanded into explicit homosexuality (primarily male), along with magical and futuristic gender-role chaos, as central features of top-selling comics for girls and women. While not featured in the exhibit, the SM! GP! catalog, as well as the Comics Journal special edition, discuss the established genre of explicit male homosexuality (aimed at female readers) known as yaoi, a term derived from the first syllables for the terms “no climax,” “no point,” and “no meaning” — though the acronym also serves for the phrase “Stop, my butt hurts!”

The show of 23 landmark shojo manga artists at C33 isn’t always easy to look at. The pieces are crowded together under plexiglass and mat board, and are confusingly organized with respect to titles and explanatory labels. Numerous pieces are hung facing the windows as a lure to passersby, which means you have to climb into the windows, putting yourself on display, in order to get a good look at some images. Artwork of such fine detail and vivid color suffers from the cramped conditions (though it’s nonetheless impressive that someone figured out how to get all the art to fit). This show in this space feels something like a high-end airbrush studio specializing in sadomasochistic sci-fi wedding portraits. However, the art is often beautiful, the historical sweep is edifying, and it’s hard not to enjoy many of the plot synopses, such as that for CLAMP’s 2003 Cardcaptor Sakura series “Tsubasa (Wings),” which includes the line: “One day, when Sakura touches some old ruins, she falls down, and her memory flies beyond time and space. To help Sakura, Yiao Lion visits a witch and begins the journey to find Sakura’s memory.” The show is additionally enhanced by a stack of free Shojo Beat magazines. This provides an important element by allowing viewers a chance to see mainstream shojo manga in its natural habitat, black-and-white panel narratives on newsprint, as opposed to the painted pin-up images that rarely appear in print, but dominate the exhibit. Seeing these soft watercolor washes, the collaged textures, and the immaculate lines up close is a viscerally dazzling experience that, in its aggressive perfection and macabre, sexually charged energy, succeeds in belying, if subtly, Western preconceptions of the feminine. At the same time, its idealized internality and open-ended imagining evokes what psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan termed “jouissance,” a state of bliss outside of language, accessible to only the female mind.

&nbps;

Cover of Cardcaptor Sakura: Master of the Clow Volume 4 ©CLAMP

A version of this essay was first published in The Chicago Reader.

__________

This is part of the Gay Utopia project. A map of the Gay Utopia is here.