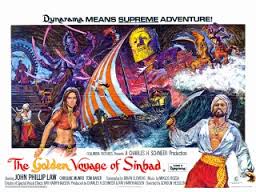

I turned seven the summer of 1973. Sinbad, the sea-fairing adventurer from One Thousand and One Nights, turned 1,207—or at least Huran al-Rashid, the 8th century caliph who would have reigned during his voyages, did. Sinbad’s a lot older if you think he’s just a Persian reboot of Odysseus, which I don’t. It’s not clear how he anchored in Arabian Nights, since Scheherazade almost certainly didn’t spin any tales about him. Ditto for Aladdin and his lamp. But the first 1880s translations (same decade that gave the Victorians Sherlock Holmes, Dr. Jekyll, and the Ubermensch) happily include both heroes. The 1940 Green Lantern was originally named Alan Ladd (get it?), but Sinbad didn’t make it to the realm of superhero comics till Marvel adapted his low budget Hollywood adventure, The Golden Voyage of Sinbad.

My aunts took me. Which probably means I was marooned in their tiny Pennsylvania smallville while my parents were off on their own voyages. I recently streamed the film online, surprised as always by my unfaithful memory. Did I really not notice the Stonehenge replica at the center of the lost island of Lemuria? Or that the King Kong-derivative “natives” were green? Sinbad also barters himself a love interest, AKA sex slave (a disturbing staple of mid-70s fantasy and scifi films—the elite apartments in Soylent Green came with human “furniture” the same year, as did the elite houses in Rollerball two years later). Our virtuous captain, of course, doesn’t exercise any of his property rights, and there’s even a marriage proposal before the credits.

Hindsight also provides certain pleasures—like watching a bunch of pasty white guys evoke Allah every third sentence. Or realizing that Doctor Who is playing the evil sorcerer (the BBC was so impressed with Tom Baker’s performance, he replaced the retiring Jon Pertwee the following year). That evil sorcerer, by the way, is oddly sympathetic, the way Baker writhes and ages a decade or two every time he employs his apparently hard-earned magic—like animating the figurehead on Sinbad’s own ship to battle him. How cool is that! His little flying homunculi were niftier in memory though—as I suppose is true of all Ray Harryhausen stop motion claymation.

The best is when Baker animates the six-armed Kali statue in the natives’ temple (though why exactly are faux Africans worshipping the Hindu goddess of Time, and, oh yeah, why are they green?). I should also mentions there’s a rather rudimentary plot device of finding a missing puzzle piece that will, I forget exactly, unlock the Fountain of Something Or Other. So Sinbad and Baker are racing each other in an overarching A Plot, which is subdivided into episodic B Plots, such as battling evil cyclopean centaurs and sailing around foggy soundstages.

It’s at this point that I turn to my nearest aunt and whisper: “The puzzle piece is inside the statue.”

She probably thought I was nuts (like that time I reflected a flashlight beam onto her bedroom ceiling while making what I imagined were UFO noises), until Kali tumbles and, yep, there’s the golden puzzle piece shining in the rubble.

She was pretty impressed, as was I, still am, though I can’t say I was much of a boy Sherlock. Things I wasn’t noticing at the time include Watergate, the civil rights movement, and my parents’ impending divorce.

I’d shrug it off as a lucky guess. Except it’s the same plot maneuver I encounter several hundred times a semester. How often does an episodic B Plot shatter against an overarching A Plot? More specifically, how often does a storyline sail out of a sub-adventure to continue its main voyage? My first year comp students navigate this map three or four, sometimes five and six times every essay they draft. A body paragraph is just an adventurous subpoint in an overarching thesis. Before exiting to the next island of green natives, shatter Kali to show why you dragged us there in the first place (ie, repeat a central element of the thesis in the last sentence). When you finally row ashore your concluding paragraph, assemble the golden key pieces and unlock the Fountain of the Passing Grade.

I realize that’s a particularly Western way of writing an argument. A Chinese essay, for example, might reflect different norms, so called “high context” ones, where inference and implicitness are an adventurer’s main magic tricks. That means a thesis isn’t necessarily stated or the map to get there isn’t drawn linearly. If Sinbad submitted such a tale in my WRIT 100, I’d have to send him back to Lemuria for revising. But if he’d grown up in my subdivision of Pennsylvania, he’d already know how the puzzle pieces work.

By what age do kids absorb such cultural nonsense as plot formula and argument structure?

I’m guessing seven.

I was hardly reading but I was already a little claymation homunculus. I’m not suggesting Tom Baker was employing me for nefarious ends. I’m just saying cultural magic seeps in deeper and faster than we might think. And some unstated sub-claims might sneak in with it. Like, oh I don’t know, women are furniture, and beware swarthy men (Baker wore make-up). Which is also why it’s sometimes worthwhile to analyze nonsense like The Golden Voyage of Sinbad.

Sinbad, by the way, made at least one more sojourn into the Marvel multiverse. He teamed up with the Fantastic Four for Chris Claremont’s astonishingly ill-timed Fantastic Fourth Voyage of Sinbad in 2001, on newsstands when the World Trade Center tumbled and shattered. Since then I haven’t noticed many cultural representations of good-looking white guys giving thanks to Allah.