Ben Schwartz posted a response/review to the first episode of the new Doctor Who season over on the main tcj.com site. I won’t summarize it in detail ‘cause it’s right here and you can just go read it. (Go read it! Support our host site! Give Ben some hits! He needs your support to counteract all the shit I’m giving him…)

Ben’s (admittedly tongue-in-cheek) thesis is that Eleven (the Doctor’s eleventh regeneration) is a “Tory” doctor – the idea being that this Doctor caves in to authority too quickly. I think this conclusion is wrong: it’s based first on overlooking the ways in which the plot of the first episode coheres internally, then overlooking how it coheres with the theme of the multi-episode story arc – the Doctor must decide whether the good of the many outweighs the good of the one – and then subsequently misreading how both that story arc and this specific story’s plot tie into contemporary British politics.

I’m not sure whether Ben feels like the old episodes are more tightly plotted than the new ones, but in my read, Dr Who has never been particularly about plot. It’s a secular morality play. If you don’t like morality plays, you’re probably not going to like this show (unless, these days, you just have a crush on the cute Doctor). But that doesn’t make it badly written. That’s like saying The Canterbury Tales is badly written because it isn’t The Lord of the Rings.

So although I think Ben is just mistaken about the plot points – something I go into in Ben’s comments section in nauseatingly geeky detail – mostly his post felt worth an argument to me because one of the reasons I do not watch a lot of tv in general is this notion, implicit in Ben’s position, that everything should be clearly spelled out bluntly and explicitly at the level of plot and dialogue, making it easy to get all the pieces on a casual viewing or two. To me, it’s the things that are not spelled out, but that can be reconciled via close reading (or even sometimes only by recourse to extra-diegetic elements) that give writing in any medium texture and life and complexity. I don’t share Ben’s concern with plotholes, but I also don’t agree that the episode actually has plotholes to be concerned about. I think it’s very tightly scripted and very well done.

Now, I’ll accept that the episode’s tightness is pretty subtle and easy to miss on one watching. (I’ve now watched it 6 times, because every time Ben said something I’d go, “Wait, what? Wait! Lemme watch that again!) But that subtlety is a tactic: just because it’s hard to catch precisely how things tie together in a single viewing doesn’t make the subtle bits “plotholes.” Having some things be tricky to figure out – but nonetheless tight – is what makes a video, tv or film or otherwise, worth watching and rewatching, that makes the viewer an active participant and rewards engaging for more than just a couple hours diversion. Dr Who is TV for geeks, which is why we’ve been watching it for 40-odd years.

So Ben and I, I think, disagree on what it means for an episode to be “well-written” because we think about plot in different ways. But that said, we also appear to have watched two very different versions of The Eleventh Hour. Ben argues:

[The Doctor] had direct contact with the Atraxi and then Prisoner Zero and was given the Atraxi message personally.

He points out that he leads the Atraxi to Zero by using his sonic screwdriver because they’re looking for alien technology — so, the Atraxi definitely know our world, that the Doctor’s not part of it, and then ignore this until it becomes a key part of catching Zero.

Ben rightly identifies the kernel of the plot in the second quote, but the details are wrong. The Doctor doesn’t lead the Atraxi to Zero using his sonic screwdriver. It’s actually fairly tricky for them to track something as small as the screwdriver. The Doctor tries to get their attention using it in the town square, and fails, because the screwdriver burns up before the Atraxi can, ahem, zero in on it.

The Atraxi don’t speak directly with him until the end, when he meets them on the roof. Prior to that, they’re just talking to his technology. Ben rightly remembers that in Amelia’s bedroom the Atraxi send their message directly – but it isn’t a personal message. It’s just the same rote “Prisoner Zero has escaped” that they’re broadcasting on every available communications medium, Earth-based and otherwise. They identify the alien technology of the sonic screwdriver and then broadcast their message directly onto the Doctor’s psychic paper.

But they don’t make the connection between the alien technologies and the biological alien. It’s not the Doctor they know; it’s the Doctor’s things. What they have a lock on is the technology they identified in Amelia’s bedroom and yard when the Doctor first arrived: that’s why they followed the Doctor away from Earth. (He says in the town square when he’s explaining why 12 years passed before they came back: “they’re only late ‘cause I am.”)

Tracking the Doctor in the Tardis is different – philosophically and in practice – from tracking the Doctor walking around. Atraxi scanning technology isn’t precise enough to find an individual the size of a human being quickly. Even with the sonic screwdriver going off in the town square and the Atraxi directly overhead, they can’t pinpoint the screwdriver, let alone identify the Doctor and Prisoner Zero, in that few seconds. In fact, although we don’t know it during the scene in the town square, the Atraxi don’t even know that the Doctor is alien until they scan him at the end of the episode on the rooftop – after he actually does succeed in phoning them. They scan him, and then they say “you are not of this world.”

So the Doctor’s being alien in fact isn’t a key part of catching Zero (except insofar as he’s smarter than we are). And the alien-ness of the Doctor’s technology doesn’t play any role either: what the Doctor did, he did entirely using present-day Earth technology: a laptop, a computer virus, and a camera phone. The Atraxi’s ability to scan alien technology in particular ends up being entirely irrelevant. Instead, what’s relevant is the distinction between the technology and the individuals who use it – and the fact that the Atraxi’s technology can’t tell the difference.

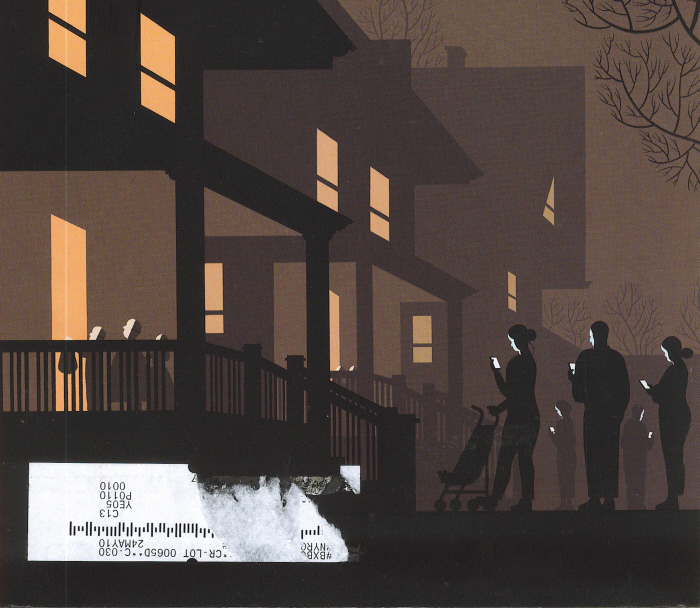

Insofar as there is something political in this episode, this is it. The use of earth technology is it. The gap between who a person is and the technology (s)he uses is it. This is well-played technology-as-Panopticon – and there aren’t many places, in the West at least, where the Panopticon has more present-day relevance than in 21st century Britain. According to the BBC, there are 4.2 million CCTV cameras in Britain – about one for every 14 people. That’s almost Orwellian, and it’s a huge issue for British politics.

But Ben gets the wrong party: the surveillance state is even more Labour than it is Tory. Officially the Tories support reductions in the surveillance state – but convicts are an exception to their plan to reduce the reach of their databases. In Britain-as-Panopticon, Labour and Tory are equally implicated. Certainly surveillance is a political issue, but it’s not one that falls out on the reductive liberal/conservative binary so characteristic of American politics.

Surveillance is instead a political issue in the Foucauldian sense. Foucault explained it thus in Discipline and Punish:

Perhaps we should abandon a whole tradition that allows us to imagine that knowledge can exist only where the power relations are suspended and that knowledge can develop only outside its injunctions, its demands, and its interests. Perhaps we should abandon the belief that power makes mad, and by the same token, that the renunciation of power is one of the conditions of knowledge. We should admit rather than power produces knowledge…that power and knowledge directly imply one another; that there is no power relation without the correlative constitution of a field of knowledge, nor any knowledge that does not presuppose and constitute at the same time power relations. These “power-knowledge relations” are to be analysed then, not on the basis of a subject of knowledge who is or is not free in relation to the power system, but, on the contrary, the subject who knows.

Surveillance is about gathering information and turning that information into knowledge about the people under surveillance. What’s at stake in this episode is not the straightforward partisan allegory, but its moral facet: the omniscience of the panopticon, and the limitations of that omniscience.

That gap between the individual and the technology, the gap the Atraxi surveillance cannot bridge, cuts to the moral heart of the very existence of a state: the necessity for individuals to make decisions on behalf of the many that affect each individual one, and the inadequacy of the knowledge we base those decisions on. Where better to explore the relation of surveillance to power than in a story where the hero’s power so explicitly comes from knowledge?

This is why the question (blustering over the Internet on Whovian message boards at the moment) of why the Doctor gives up Prisoner Zero without any evidence of his guilt is missing the point. Foucault’s insight is that the perspective of the Panopticon is not just about monitoring the prisoner – it’s about the way in which the ability to monitor individuals creates a category of citizen subjectivity unique to the modern state: individuals are transformed by surveillance into objects of knowledge.

That’s what Prisoner Zero is to the Atraxi, and by the force and necessity of his power-knowledge and the limitation of Earthly time, to the Doctor as well. The Atraxi mothership is a Panopticon – in concept and in design – but it is the Doctor who is all-seeing. Zero’s body is trapped in a forcefield of power and knowledge articulated by both the Atraxi and the Doctor: a forcefield that renders any sense in which he might be “not guilty” irrelevant – secondary in the face of the need to “govern” and “protect” the rest of the world. The state depends on the prisoner. The sacrifice of the one is necessary for the good of the many. The Doctor, like Foucault, knows this – and it makes him sad.

This is the point Ben misses when he insists that the Doctor jumps when the Atraxi flash their badges. Yes, the Doctor is complicit in the use of surveillance technology against Zero – but when the Atraxi take Zero, the Doctor’s expression is heartbroken. He’s genuinely sorry. It’s not a rote caving to an external authority; it’s recognizing that no individual beings matter in this universal, timeless, always existing field of power-knowledge. The Doctor recognizes his own subjugation to his own power.

But he also recognizes that he is the one individual in a position to determine whether the field of power-knowledge serves good or evil. (I’m wondering whether this will be a theme in the upcoming Churchill/Nazi/Dalek episode.) The Doctor, contra Foucault, turns the surveillance technology back against the Atraxi too. He subverts the Atraxi by turning their attention FROM the technology TO the one individual who does matter in that field, the individual in the Panopticon, the organic, living Doctor – the Doctor who protects the Earth. The Doctor who is our Superhero. The Superhero whose superpowers are his compassion, his mind, and his knowledge.

This is why I just don’t think this episode can be easily reduced to partisan politics, as Ben suggests, or even to simplistic questions of whose authority is most compelling.

Doctor Who doesn’t just have knowledge and a conscience. He has the power to make decisions that challenge and test the limits of his conscience, and that have consequences for individuals – individuals with whom he feels genuine compassion but over whom he nonetheless has power. Ben not only completely diminishes the complexity of this story when he overlooks how much the Doctor struggles with this role; he diminishes – like so much of contemporary politics in the age where the most powerful Panopticon is the eye of the media – the extent to which political good always relies on the ability of those individuals fortunate enough to sit in the panopticon to watch themselves as clearly and as vigilantly as the prisoners below.