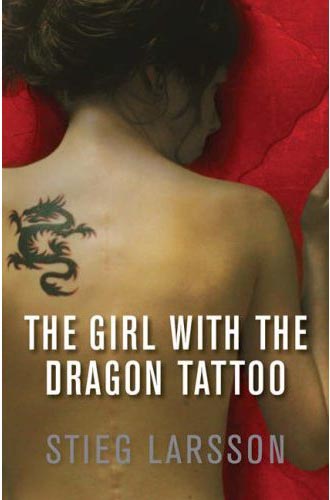

Sometime commenter on HU Monika Bartyzel had an thoughtful post about the softening and sexualizing of Lisbeth Salander in the Hollywood version of “Girl with the Dragon Tattoo.” I talked to her a little about it on email, and she kindly agreed to let me publish her further reflections. So here they are:

I appreciate the book. As you’ve already seen with Twilight, I can read around certain issues if I find something compelling or interesting. I so completely appreciate his [Stieg Larsson’s] intent and the path he takes that any literary questions of value/etc are irrelevant to me. The only thing that did really weigh on me was supposed to – it was hard work to read about repeated abuse to one woman, but I think it was entirely necessary to make the environment palpable, especially to those who would deny it…while also noting that even with just a sliver of what Lisbeth experiences, the audience sees it as too much. It adds weight.

As for similar problems – do you mean in her characterization or the film? Yes, the film is dense and not structured in the usual way (again, I don’t mind that). As for her – it’s similar yet very different. It basically boils down to privilege and how stories are filtered. Larsson saw a rape and wrote from the vantage of being emotionally impacted by the continual violence against women that he saw. Fincher is coming from sexy Hollywood of flash and lust.

So through Larsson and on the page, Lisbeth’s vulnerability is more about the men than about her (though her body is slight). She has things happen to her that she can’t control, so she reacts in an entirely different way to the world than we do. For her, in the book, she feels like she’s given a lot to Mikael and has deep feelings for him (love? No idea. She cares for him, but there’s no base of comparison). So when he walks off with his long-time paramour, she’s hurt and writes him off. But she wasn’t womanized. She wasn’t a romantic fool. There was never a moment of dual intimacy. To her, she’s sharing a lot; to him, she’s cold, aloof, and fascinating, but not warm. It’s a look at her struggle to find the balance between who she became due to her terrible life, and the human feelings and impulses she has. Some say that it’s ludicrous that she’d even like Mikael, but it’s not. He’s the second kind man in her life, the first who isn’t a father figure. He isn’t a misogynist, he’s smart, fit, and comes to her in a place of warmth and kindness that immediately gets under her skin because no men have this obvious, inherent respect for her.

Fincher takes the vulnerability of a girl whose legal and human rights are continually ignored and thrusts her into a two-part personality of the soft girl who just wants to be loved and the hard girl who will kill if she’s crossed. So to him, her sneers are sexy, rather than sad or unfortunate. He makes her obviously romantically interested in Mikael. He makes her share dark secrets and openly trust him. He makes her the emotional hero and

Mikael the man who broke her again. He takes away the context around Lisbeth so to understand her, you fill in the blanks, and since she’s been infused with more classic Hollywood portrayals, the blanks are filled in with assumptions that defeat the purpose. The biggie for me: In the book she’s attacked by drunk guys and her computer is broken. No one helps her and it helps to set up how men continually try to prey on her. In the film, it’s just a thief, and she’s just a tough ass-kicker. It glamourizes it at the expense of the painful truth.

You can read Kinukittys’ discussion of the film here. Richard Cook’s take on the book is here.