‘And through the breach did march into the streets,

Where, meeting the rest, ‘Kill, kill’ they cried.

Frighted with this confused noise, I rose,

And, looking from a turret, might behold

Young infants swimming in their parent’s blood,

Headless carcasses piled up in heaps,

Virgins, half-dead, dragg’d by their golden hair,

And with main force flung on a ring of pikes,

Old men with swords thrust through their aged sides,

Kneeing for mercy to a Greekish lad,

Who, with steel pole-axes dash’d out their brains’

(Christopher Marlowe, Dido, Queen of Carthage 2.1.189-200)

1998 is a significant year in Indonesia’s political history. After a 32 year rule characterised by economic prosperity and an authoritarian regime, the Asian financial crisis had weakened the rule of then-President Suharto. In May 1998 riots broke out in several Indonesian cities. The estimated death toll from the days that followed varies wildly. Jemma Purdey, perhaps one of the most reliable sources, suggests that around 1,000 people died, many of them beaten, shot, or burned alive. Women were raped and then thrown out of windows, shops were looted and then burned to the ground with their owner’s still inside. Calls to the police went unanswered. For some time the army stood by without intervening. Colleagues of mine who were in Jakarta at the time saw people stripped naked and left by the side of the road on the way to the airport. One described the bizarre scene of soldiers breaking away from a gunfight in order to ask her and the other expatriates she was with to pose for a photograph. People stayed in their homes and listened to screams and gunfire on the streets outside.

For many of the perpetrators of violence in 1998 the riots offered a fresh opportunity to target Chinese Indonesians. Historically, Chinese Indonesians acted as middle-men between the native Indonesian population and the Dutch. Both during and after Dutch rule they have been subject to periodic outbursts of wide-scale violence including not only massacres but mass-expulsions from Indonesian cities. During the decades under Suharto many Chinese Indonesians were killed under the guise of wiping out communist activity. During the 1998 riots, in many cases the violence toward Chinese Indonesians was misplaced – it was those Chinese Indonesians who were least wealthy who were most vulnerable to attacks. Chinese Indonesians were not the only victims of violence during the riots, but they were certainly singled out as targets.

On May 21 1998 Suharto was removed from power. The era which has followed has been characterised by a movement from dictatorship to democracy, with greater recognition of Indonesia’s multi-racial and multi-religious status. While these changes have largely been beneficial for Indonesia as a whole they have also, as several commentators have argued, been accompanied by an unwillingness to examine what took place during the May riots. This is true in a legal sense – attempts to bring suspects to court were unsuccessful, and those rape victims who did come forward have failed to have their rapists identified or convicted. It is also true in a cultural sense. As Abidin Kusno persuasively demonstrates, the building of the Glodok Plaza Mall at the site of one of the major massacres is emblematic of the cultural work which took place after the riots; it prioritises progress over commemoration in the hope that the spectacle of the new will distract people from the violence of the past. Despite its pervasiveness in Indonesian consciousness, literary and artistic responses to what went on seem, surprisingly, to be few and far between. I have written elsewhere on the work of artist FX Harsono, but in what follows I want to look at some of the comic books created in the aftermath of the violence.

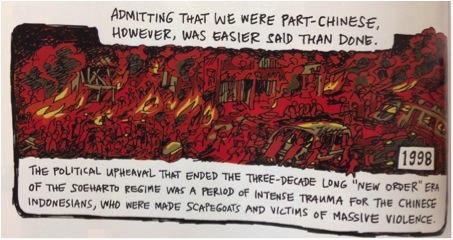

In Tita Larasati’s comic Bloemen Blij, Plukken Wij which appears in the volume Liquid City: Volume 3, the protagonist learns that she has Chinese Indonesian ancestors. The riots, in contrast to the predominantly green and yellow pastel panels elsewhere in the comic, are represented as a blood-red band cutting across one page.

This image, I feel, comes close to representing what 1998 meant, or has come to mean, for Chinese Indonesian communities. Buildings are burning, busses are being pushed over, bodies are lying in the street. Each figure is captured in just a few lines. The image focuses less on the individual acts of violence than the scale of the event. Indonesia is ablaze.

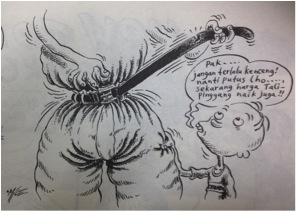

Muhammad Mice Misrad (Mice Cartoon)’s Indonesia 1998 offers a very different vision of what occurred. It is a collection of single-page comics drawn between 1998 and 1999. The collection was published last year. They document the conditions which led up to the May riots, most significantly the crippling effects of inflation during the late 1990s. One series of panels shows people trying to buy basic necessities only to discover that prices have increased dramatically in just a few days. The author reports that publishers are closing down, he attempts to buy paper to document the problems himself, only to discover that paper, too, has rocketed in price. He is only able to draw because his brother can steal paper for him from his workplace. In the panel below he tightens his belt while a child warns ‘Don’t pull to hard, sir, or you’ll sever it! Belts are expensive now too!’

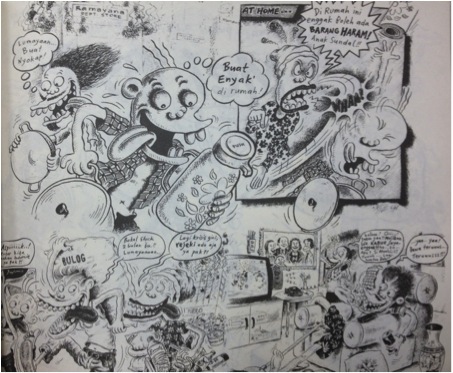

The May riots are, in this context, presented as the inevitable result of a starved and impoverished population trying to feed themselves. In comparison to the several pages describing the economic conditions which anticipated the violence, the riots themselves occupy just one page. In the image below one looter is excited to have stolen a gift for his mother, who then scolds him for bringing illegally-acquired goods into her home. Another family is excited at having acquired a two-month supply of Indomie instant noodles. One remarks, ironically, how lucky they are in such a crisis. In the final panel a woman, presumably a maid for a Chinese Indonesian household talks to a friend on the phone – her boss has fled the country and so the domestic staff (Muchilis – most likely the family’s driver) is watching soccer on television. The absent family’s portrait, characterised by round cheeks and squinty eyes, hangs on the wall.

What strikes me about these images is the absence of any reference to the acts of murder and sexual assault which sit at the heart of Chinese Indonesian and other victims’ accounts of 1998. The goofy characters and cartoon violence belie the very real bloodshed which occurred. The Chinese Indonesian family we see in the picture, we are assured, have left town.

Mice Cartoon’s comics are cheeky, iconoclastic, and witty. This charm, in this case, disguises the wilful marginalisation of the victim’s experience. This is far from trivial – the unwillingness to recognise the suffering of Chinese Indonesians and other victims in Indonesian discourse after 1998 is a necessary prerequisite to the lack of public recognition of what occurred. Chinese Indonesians are rich, popular discourse seems to declare. They can take it.

One image from the comic which I find captivating is the visualisation of the new era of free speech. A government minister tentatively removes the padlock which has closed the mouth of Indonesia’s press, revealing a sharp-toothed monster ready to bite into politicians.

I find the image less interesting for the way in which it attests to the status of the modern Indonesian press – it simplifies a movement away from the prohibition of the Suharto era to modern Indonesia. In reality, as the wildly varying 2014 election result announcements demonstrated, Indonesia’s press continues to be controlled by those in power (even if that power is now primarily financial rather than political). The internet is censored and Indonesia currently boasts an unimpressive rank of 138 out of 180 countries in the Press Freedom Index. What I find captivating about the image is its representation of violence unleashed. This gleeful creature with a giant mouth and razor-sharp teeth, set to chew all in its path, I think, approximates what 1998 must have looked like for those who lived during and after the violence.