In their essays on the recent appreciation of Jaime Hernandez at the TCJ website, both Noah and Caro ask, What makes JH’s work a masterpiece, and if you can’t tell me that, then why should I, as a potential reader, care? These are good questions. And I’m going to provide an answer that, in the spirit of HU, should piss-off just about everybody. Ready?

In their essays on the recent appreciation of Jaime Hernandez at the TCJ website, both Noah and Caro ask, What makes JH’s work a masterpiece, and if you can’t tell me that, then why should I, as a potential reader, care? These are good questions. And I’m going to provide an answer that, in the spirit of HU, should piss-off just about everybody. Ready?

The TCJ appreciation is not about Love and Rockets but its readership. This is necessary and also unfortunate.

Before I go on, let me clarify two things. First, I’m using the term masterpiece in its colloquial sense, as in a superlative work. I’m not going to worry over canon formation here, nor am I going to suggest the need for criteria for determining worth relative other works. Second, by arguing that that TCJ roundtable is about the readership and not the comic, I don’t mean we should disregard it. As will become clear, I think Love & Rockets is, and always has been, part of a conversation about what comics can be. To read Love & Rockets without reading the conversations about it would be to read only part of Love & Rockets. Basically, I’m arguing that the quality of the comic book Love & Rockets is less important than its role in creating a reading public of a certain character, bound together by their shared attention to the comic.

This argument derives from the work of Michael Warner, whose book Publics and Counterpublics argues that publics are the outcome of texts that address them as such. So, I’m going to offer a quick and dirty account of Warner’s theory of publics, explain why it is important to understand contemporary North American comics not simply as works of art, but as loci for the formation of publics, and finally, why assessing the quality of Love & Rockets is, in many ways, beside the point of the TCJ Roundtable. I’ll also argue that this is OK.

Warner makes the case that a public is created by shared attention to text. Texts, he argues, “clamor at us” for attention, and our willingness to pay attention to certain text and not others determines the publics we belong to” (89). By giving our attention to a text we recognize ourselves as part of a virtual community bound by that shared attention, and as part of an ongoing conversation unfolding in time. The classic example would be the local newspaper, which in addressing its readership constitutes each reader as a member of a locality. The daily paper does this because it encourages readers to imagine themselves as part of a virtual community, defined by a common civic-mindedness and a commitment to that text as a way to make sense of the multiple texts affecting their lives. They do this not only through reading but also through letter writing, impromptu conversation, and so forth. The daily newspaper metaphor points to another aspect of the relationship between texts and publics; namely, the publics constituted by texts “act according to the temporality of their circulation” (96). The daily rhythm of the paper is a daily reminder of one’s status as part of a public, a status that is part-and-parcel of one’s identity.

The flipside of this is that if the text ceases to receive a level of attention necessary to sustaining it, not only does it go away, but so too does its public, and with that public, a part of each member’s identity. Understood as such, it is easy to see why the cancellation of a TV show, magazine, or comic book creates a level of anxiety seemingly disproportionate to its quality as an artifact. Publics exist by virtue of attention, something that in today’s world, has been stretched incredibly thin. We’ve got many, many texts vying for our attention. Moreover, traditional rhythms of circulation have been thrown out of whack by innovations in comic book publishing, and, as Warner himself notes, the Internet. But I’ll get back to these points in my discussion of the TCJ roundtable. Now, I’m going to explain why this theory of publics is crucial to understanding North American comics.

Here’s a bold statement that is likely as false as it is true: North American comic books have, until very recently, been a means to public formation first, and a art form second (if at all). And this includes Love & Rockets. I’m not an authority on comics history, but my understanding is that superhero comics took off in part because they were created and edited by members of the science fiction community—a public constituted by fanzines—who understood itself as defined by its devotion to a textual form that many in society treated with contempt. This sense of community was fostered in letter columns, fanzines, and eventually conventions. It’s even easier to see public formation in Marvel superhero comics… Stan Lee addresses the readers as friends, in on the joke, but also serious about what the text they’re reading means to them relative other publics (true believers vs. everybody else). He directs their attention to the history of his comics’ circulation, he answers letters, and he asks readers to find mistakes in continuity. In exchange for their attention to the minutiae of circulation the careful reader receives a “No Prize,” as if to say that attention is a reward in itself. After all, its what makes you part of a public, which is what makes you who you are.

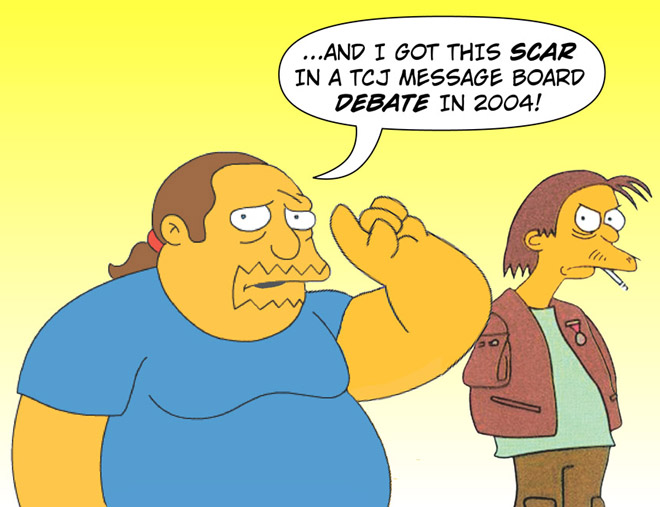

Love & Rockets emerged at a decidedly different moment in comics’ history. This is important because, as you will recall, publics act according to the temporality of their circulation. The public L&R addressed was the public bound together by the ruminations of The Comics Journal, and of other comics aspiring to a level of artistic sophistication that had yet to be realized in a significant way. It was, in short, a text that in its initial incarnation constituted an audience in a manner consistent with its aspirations for the medium. It was part of the medium, inasmuch as it came out regularly, ran letters, and so on. But unlike the superhero comics that surrounded it on the racks, Love & Rockets did not assume a new readership every five years. Nor did it require a status quo be maintained in order to insure the brisk sales of toothpaste and hastily cobbled together cartoons. In short, it promised comics readers a text that would reward sustained attention, and honor their identity as part of a community of readers over the long term. (This suggests that Dave Sim’s commitment to 300 issues was crucial to constituting the incredibly robust public constituted by Cerebus. But that’s a whole different post.)

What is remarkable about Love & Rockets is that it has made good on this promise for many years. Moreover, its publisher’s commitment to keeping the books in print has made it possible for the public to grow. And aside from the occasional detour, Jaime’s central storylines continue, which allow for the renewal of a reading community… a public that understands itself as defined by its ongoing attention to the text. This is no small thing in an age when publics from and dissolve according to the logic of direct-market orders and cross-media synergy.

That said, the rhythms of its circulation and appreciation have been disrupted by changes in the comics market, and in the forums for discussing it. When Love & Rockets began, it’s public entered into a relationship with the text fostered by the weekly trip to the comics shop, the letter column, and fan magazines like TCJ. As Frank Santoro pointed out in his “The Bridge is Over Essays,” Love & Rockets is no longer part of a larger community of comic readers. It comes out as a book now, and not in a monthly pamphlet. This isolates its public from the institutional frameworks that incubated it. Similarly, with the end of TCJ’s regular publication in print, and the balkanized world of online criticism, consensus about what comics are worth reading, what comics criticism should look like, etc. The public constituted by Love & Rockets is understandably nervous.

This talk of publics, and the disruptions to Love & Rockets rhythm of circulation leads me to why I think the appreciation is necessary, but also unfortunate. The roundtable in necessary because it does what public must periodically do to maintain itself in the face of threats to its existence. Hernandez just produced a work that by his own admission he will have trouble following up. Absent the imperative to monthly publication, and of a regular, print forum for praise and blame, the burden to compel the effort falls to the public that exists because of it. What we are seeing here is epideictic rhetoric, an effort to affirm a public’s taken for granted ideas in order to argue for why Love & Rockets should continue.

The appreciation is also unfortunate. It is unfortunate because is relies on shared and implicit assumptions to bring the community together, which in turn implies a certain “you had to be there” exclusionism. In this respect, I agree with others that more attention to the “why” of Love & Rocket’s value would have been salutary to the goals of the appreciation. In this respect, the appreciation was a missed opportunity to expand the public.

Ultimately, I think we have here a really interesting example of the intersection between artistic form and ritual performance. That it inspired the HU to go off on taken for granted values (Love & Rockets as soap-opera in particular) also suggests that whatever threat the Internet poses to this public, it also puts it into a larger conversation. So, while the bridge between publics is gone, its been replaced by a confusing, and to my mind much more interesting, network of bridges.

_____________

This is part of an impromptu roundtable on Jaime and his critics.