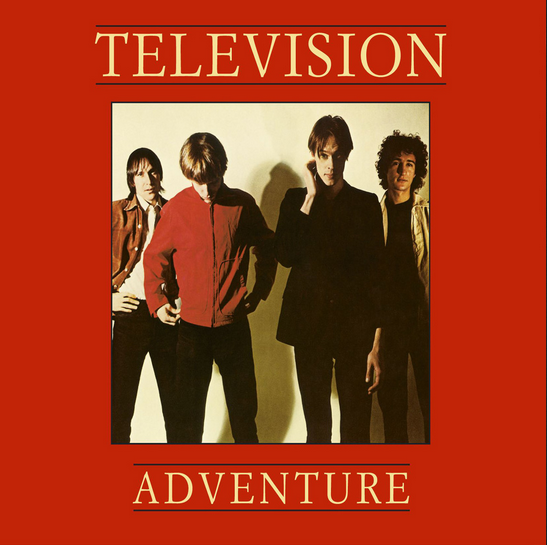

Compare and Contrast Television’s second album, ‘Adventure’ with its predecessor: the seminal ‘Marquee Moon’.

‘Seminal’ is such a disgustingly overused word in rock criticism, but there’s no doubting how many British and American bands were spawned out of Television’s singular songwriting, aggressive yet glowing guitar attack and non-Bonham drumming. You can also hear plenty of copies of Tom Verlaine’s strangled yelp and Romantic, Impressionistic and Surreal lyrics in many singers popping up from the early 80’s onward. I’m not saying they were on their own, or even that they were best at it – but they sure are there. For one album at least… Of course The Sex Pistols only really released one album and ‘changed everything’ too, if you are to listen to some people….. I’d like to show that Television completed at least 2 great albums in the following transmission:

OPENING CREDITS

TV = Tom Verlaine – lead vocals, guitars, organ, piano, slide guitar and guitar solos on Foxhole, Carried Away, The Fire and The Dream’s Dream.

RL = Richard Lloyd- backing vocals, guitars and guitar solos on Glory, Days, Careful and Ain’t That Nothing.

FF = Fred Frith – backing vocals and bass guitar.

BF = Billy Ficca – drums and jazz.

THEME SONG

‘Adventure’ could never live up to ‘Marquee Moon’. Like ‘Never Mind the Bollocks’, ‘Spiral Scratch’, ‘The Ramones’, ‘Unknown Pleasures’ and Talking Heads’ first albums – ‘Marquee Moon’ has created its own genre within punk and new wave. It’s a shame; coz here is where the show gets really interesting! ‘Adventure’ is exactly the right second album to put out after such a game-changer. It’s a step down, but it’s also a step across… it’s not called ‘Adventure’ for nothing!

PART ONE

It starts from the album cover. It’s still the same bold and plain group portrait with a large border and clear titles, but ‘Marquee Moon’ is in midnight blues and blacks – ‘Adventure’ in fiery afternoon oranges and reds. The band photo itself shows a difference from the bleeding saturated colours of ‘Marquee Moon’ to the crisp, over-lit Adventure line-up. Words could be written about the actual band pose here: RL going from insouciant glance to a look to the floor, FF again looking like he’s just jumped into the shot and TV out front and in charge, but trying not to look it. Eyes straight ahead.

&mbsp

The only tune that could have really fitted on ‘Marquee Moon’ is ‘Foxhole’ and it is the only mainstream visual account of the real Television, recorded for The Old Grey Whistle Test, BBC2 in 1978. Give Thanks to the Beeb!

GLORY opens the album like a winner. An up tempo tune like ‘See No Evil’’ RL delivers a typically brilliant solo – clean, precise and angular. In and Out. The sound is classic, yet new – after all the fuzzy, phasey, echoed excesses of the early 70’s: this is Fender guitar into Fender amp and turn it up… The approach (unlike TV’s) is one of beauty and simplicity. I read once how he preferred the first two Jimi Hendrix albums against all the rest because Chas Chandler would not allow excess. He really takes that to heart in his soloing throughout Television’s career. Try ‘Elevation’ on Marquee Moon to see what I mean: sharp corners and exotic bends – but over in seconds…

DAYS is probably the prettiest love song they could ever play and yet RL’s parts and solo takes it off into a reverie that lifts the song into a more British folk-rock level before it becomes too boring. I think it’s worth mentioning here – coz nobody else has – how much the songwriting AND the guitar approach echo Fairport Convention post ‘Liege and Lief’. Like ‘Ain’t That Nothing’ it follows classic pop lines, but played by anxiety ridden retards. TV was never a good singer and the fact that most of this song hinges on a 3 part harmony hook helps make it the most radio-friendly tune in their catalogue. It would have never been a hit…

Speaking of radio-friendly, this is the main issue with this second album for me. There are two brilliant Stones-esque songs on Adventure. This, in the hands of lesser bands would have made a career, but not in this show. ‘Ain’t That Nothing’ and ‘Glory’ are fresh-out-of-the traps rock’n’roll with enough originality to get the public interested. Either one of them would have made a decent radio hit with enough promotion. Television had already had minor chart success and MAJOR critical success by now. There’s a fair few tunes on Adventure that could have caught the public ear. But they don’t quite tell a vision…

FOXHOLE comes on like a natural successor to ‘Friction’. Grinding and stuttering and aiming just over the head, it’s probably the least ‘produced’ song on the album. The TV solo here starts with 2 or 3 harmonics bent out of shape before developing into a cross between the solo’s in ‘8 Miles High’ by The Byrds and ‘Little Johnny Jewel’ by his own band. The bass, drums and RL guitar grip as hard as on ‘Friction’ or ‘Prove It’ from Marquee Moon with added depth and grease. You can almost hear the bullets fly by your ears. By the time TV hits his last few manic run-up-the-string licks it’s time to get out of the warzone.

I DON’T CARE seems to be the album’s light-hearted moment, where once ‘Prove It’ stood. But unlike that great tune there are no dramatic flourishes of TV guitar or BF drums or even a clever lyric. A rather skip-along country feel is topped off by plainly strummed guitars and a high chorus line. A little bit too high for their voices in places. Both ‘Prove It’ and ‘Little Johnny Jewel’ show how TV can write a witty couplet when he wants to, but not here. Possibly the weakest thing the band ever committed to vinyl, but luckily followed by one of the strongest!

CARRIED AWAY appears at the end of side 1, occupying the place of Television’s signature tune. And it doesn’t disappoint there. There are acres more production features now, but it serves a beautiful song. Not known for their middle eighths or advanced song structure, Television look to break the pattern here. In fact each new part of the song, while not actually changing chord patterns or anything, seems to bring a subtle development in the playing and production. The lyric gets more Romantic, more unfocussed and more abstract as the track goes on. The overall atmosphere feels like the whole band is growing louder yet getting further away.

This time the tune is only just over 5 minutes as opposed to 10, but you really think you’ve been through the changes after it, just like with ‘Marquee Moon’. Judicious application of keyboards is what makes this tune stand out too. I assume they could afford to rent a Hammond Organ now and so they do: letting it take the main theme, like it was Dylan circa ’65. There is an insidious creep in the bass line and guitar motifs (initially) that seem to suggest we’re in for another tale of modern horror. We are not though – it’s the gentlest song the band ever made. The words talk about a quiet walk among the docklands of NYC, feeling the elements and blending with them. The Romance comes through in almost every line and sound.

Possibly the most ‘Fender’ sound of all time is employed throughout this song. A slow throbbing tremolo from the rhythm guitar, one chord a bar. Thank the lord for spring reverb and single coil pickups. They carry an atmosphere all their own! Every member of the band seems to be telling the same story, fixing to the same shadowy outcome. Like ‘Little Johnny Jewel’ it seems to be rehearsed yet free… and it’s got the perfect vocal hook line too. Should have been a classic…

AD BREAK

I’ve read allsorts of interviews with TV over the years and he seems like a bit of a bullshitter to be honest. There’s no doubting that he’s telling a vision, but he seems to love obscuring the efforts of others in his work. Me ME ME seems to be his preferred position. Clearly something was always wrong with his relationship with RL, but both FF and BF have played with him throughout his career and he’s never nice about either of them either!

BF, like John Densmore, uses his kit as an expressive tool, but never stops hitting them on-beats like any good rock drummer. There’s an adventurousness to his playing that was copied so much in the UK – The Banshees, The Slits, The Bunnymen all took a cue from him, but weren’t as technically innovative and inspired to do something every 4 bars. He’s jazz, no doubt… FF too is sorely underrated as a bassist. He’s more accurately called a Bass Guitarist because he’s often playing complimentary lines and contrasting rhythms with the 2 guitars. I suppose this is where the comparison with the Grateful Dead comes in: both bands are using the same 3 instruments to weave a big harmonic and rhythmic web.

PART Two

Now that Television’s new sound world has been established, it’s time to let it flourish. Flipping over the original vinyl record and you are faced with only three tunes, two of which again break the five minute mark. If this side were the last bit of sound before we switched the Television off, it would have been a great end. The second side shows where they were going: into a clearer and purer sound world. Maybe they decided to put all their weirdest and noisiest stuff on Marquee Moon coz they thought they would only get one album? And when a next one was required they dug around the back catalogue? Maybe the second side of Adventure shows what would have been? I think so. There are a few bootlegs where they feature The Dream’s Dream and The Fire at the front of the set – basking in glittering newness and then they play the arse out of the old material.

There is beautiful development there on the second side of the LP. With the most straightforward of sounds, an ample sense of space, cool lyrics and a soft touch Television made a great second episode… watch it!

THE DREAM’S DREAM opens like no other Television song before. A Theremin-like slide guitar squeals a melody over organ pads. RL is nowhere to be seen. BF and FF creep in slowly and surely. It’s a chord progression like ‘Torn Curtain’. The whole track lights up permanently once TV’s lead guitar enters before the chorus. The songwriting steps out now too, accompanied by TV’s loose and spectral licks. Again there’s an almost broken series of lyrics and guitar fills that make the show feel like it’s improvised and on the spot – but it just can’t be. There’s too much interplay between TV and the rhythm section. Too many little jerks, and the lyric only sets out to make it more confusing….

AIN’T THAT NOTHING is the strongest contender for ‘Television’s Big Hit Single’ as the guitars, bass and drums all coalesce into a controlled but flailing whole. Real punk energy pushes along a straightforward boy/girl lyric and TV manages to sing ok.

k,,

THE FIRE suggests that their 3rd album would have been a killer. A four piece rock band, with minimal equipment and production, could make a purely ambient album.

The lyric and voice disappear behind a mesh of glistening guitar, gradually getting used to the space and filling it. Reverb creeps in. There are no major psychedelic effects, but the affect is definite. Television never needed too much production to create an alternate space. FF’s bass suggests things. BF stretches them out. Like ‘Little Johnny Jewel’, the whole song sounds improvised but structured. It fades and throbs between passages with TVs guitar always near. But unlike that song there is no central motif this time, it’s a jumble. Yet gripping. How do they do that?