The Extended Laces

or, Drusilla’s Fatal Brochure

By Claudia Fonce Earbrass

Author of The Unsprung Trampoline, A Thousand Pins, Why?, The Applecramp Sextet, Did She Remember?, The Fantod Regrets, and A Scent of Cedared Fields

Hello to everyone at xL Design Studios. Neil here and very happy we have this chance to work together. So, the title page. Very much suggest central image plays on sneaker and laces, with the laces in advanced state of extension, just sprawling out there. That’s recto. Verso, we have the comic book, and that’s tattered and it looks like it’s been flung wherever it is—pages splayed, whatever. Placement of the title and byline and the “Author of” book titles: entirely up to you. Whatever works, and never mind about using all the book titles – we’re perfectly comfortable with their serving as design elements at your disposal. That being said, Scarlett said to tell you she likes The Applecramp Sextet.

Drusilla was left for the day in her family’s unexplored new home.

All right, first page. Think we discussed the kinetics, the set up for the flow we want from page to page. Kieran’s handling that, am I right? Hello, Kieran.

Drusilla, house, car. Car’s taking off, house looms, Drusilla looks at it, her back to the car. Car: mid-’70s vintage Volvo. House: not a teetering wreck, not necessarily a haunted house, but a big pile with many windows and ledges and little roofs, and so on. Drusilla’s look: as discussed. Skirt, sweatshirt, sneakers. Alinor, did you send the studio the character profiles? She says yes, so I expect you’ve got it. If not, text her, she’s on duty to look out for such things.

Just want to reiterate here that Drusilla’s sneakers and laces are in view from the outset and page by page. Always in view, laces always untied and getting longer.

Her parents absented themselves to join in a sordid debauch.

Tricky one. We want a very post-hippie, mid-70s feel: longish hair, wine glasses, joints,, jeans, tennis shorts. Perhaps a stereo with speakers out on the lawn, if feasible with regard to panel space. But here’s the balancing act I was talking about. As discussed, we want all that in the idiom of our source artist. At the very least, probably kohl darkening around the characters’ eyes. Anyway. When we see them, the participants are sprawled on the lawn in a sodden tangle. And there’s suggestiveness, what with shorts, blouses, etc., tugged awry.

Drusilla set herself to know her new surroundings.

Hi. Alinor here. Neil has to field a thing, so I’ll be passing on his notes and so on. All right. All … is this page 3? All right, his notes say: “inside house, big stairs leading up, dark, Drusilla at foot of stairs, one foot edged to ward them, expression dubious—posture like p. 1, Gilded Bat.” And he has “Period detail, if poss: ’70s again.”

There was a box under a bed she did not like to think about.

All right, that’s pretty clear. Bed, box under it. A cardboard box, quote, “as from a liquor store,” but Neil says no brand names, etc. Unmarked box. “Packed full a long time, strained at seams, flaps dented and wrinkled.”

Drusilla looking at box, Neil says: “expression similar to-—“ Oh, sorry, can’t make it out.

But its attraction proved too powerful.

Neil just texted to say Professor Bloom very much likes Scent Cedar Fields. I don’t know. I guess you know what that is.

Anyway, Drusilla pulling out the box.

The pamphlets she found baffled her understanding.

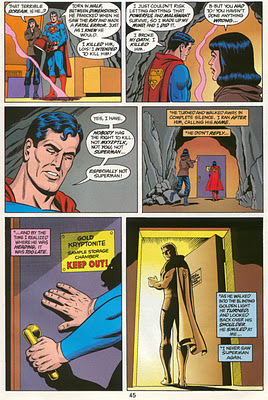

Now we have the comics, magazines, etc., that are in the box. Neil says, “Tricky, the balance again.” I guess you know what that is. Okay, quote, “suggest no pictures, titles on covers, except House Mystery, H. Secret, 1 of each.” And he says have the comics, quote, “really flung about, a couple small drifts of them.”

She read them with an undeniable fascination.

And this is like before, but now she’s on her stomach and reading one. And, because this is triple underlined, and behind her, in the doorway, the doorway’s left side, we see the last bit of a superhero ankle and heel, like, quote, “a superhero was just passing by and this is all we glimpsed.” Drusilla doesn’t see, and that’s underlined too: “Drusilla no idea.”

Her parents’ return startled her. Pushed by an instinct she could not name, she hid the booklet.

And now she’s moving about, getting the comics back in the box. Neil’s note says, quote, “Drus’s posture v.v. Gilded Bat. Visual humor from contrast of frenzied activity and elongated, immobile posture. Gilded Bat good reference.” So he wants you to look at Gilded Bat. And the “v.v.” means “very, very.”

Henceforth, she regarded the whole matter with misgiving.

Hallway, the doorway, Drusilla. I mean, Drusilla’s out in the hallway and looking through the doorway, and we can see a corner of the bed. Drusilla’s expression, the notes say, her expression is, quote, “the comic, blank foreboding found on G’s children, white faces, slit eyes, features minimal.” And then he has “Wugg-Ump.” I don’t know.

Years passed.

Note says “Drusilla. Same skirt, sweatshirt as before, but she’s teen. Dinner table, parents, rec parents from crowd on p 2, the sordid debauch. Refer character profiles.” Okay, and I sent you those, so we should be okay. He has “Kieran: D seated panel right, profile left.” So if there’s a Kieran, I hope you get that.

At college she made difficult friends.

Neil, quote: “Spooky, emptied-out coffee shop, student hangout but depopulated. Suggest great elongation, extension of decor—not just an unhealthy-looking rubber plant but one that twists its way higher up than it should and looks like it may collapse of its own sickness. And on like that. Standard items found in a college coffee shop, but seen a certain way.”

Okay, Drusilla and two friends at center but in the background … Oh, hi! Should I …

Hi, Neil, here. Yeah, okay, Ali, thanks for that. All right, page 11. They have the character profiles, right? Okay, two friends as described in the character profiles, use your design judgment as to where they’re placed in frame. But, and this is key, Drusilla’s laces are getting long now. We start to notice.

She searched for her creativity.

Drusilla at a performance art piece by students. I mean, she’s one of the students, taking part. Knock yourself out on this, re: costumes. Note: all girls more elongated and slinky than Drusilla, who looks a bit slumped around them. And there’s the laces. By this point, looking at them, one might wonder how she walks without tripping.

The childhood pamphlets sometimes returned to her mind, always at unexpected moments.

Right, same performance. Drusilla, foreground and to the right, eyes on one of the tall, elongated girl students striking a mock-Superman pose, a generic superhero sort of thing, with cape behind her, leg flung back, arm flung forward, all this suggesting flight. Nothing else to suggester superness, just the cape, which is blank, and the posture.

And there’s Drusilla looking. Laces in view.

In the background, as if peeping in from backstage behind the performance art show, there’s a superhero’s gloved hand and the edge of his caped-and-cowled shoulder and side of the head. Just enough so that a sharp-eyed reader can see.

Her parents remained irritating.

The dining room table, as in the “Years Passed” picture. Drusilla home from college. Parents older, squabbling, entirely caught up in each other. Maybe D has a Discman on and its playing. Laces longer; we can see one or both lying along the floor like a snake sunning itself.

In the city she found a career.

Drusillla, same posture, same place in panel as on page before. Now she’s at an office, computer screen in front of her. The monitor is one of those clunky jobs from the 1990s. Scarlett adds, quote, “Very then.”

And spent time alone.

Now in a movie theater. Same posture as last two pages, but now she’s angled toward the panel’s rear, toward an out-of-view movie screen. Empty seats on either side of her, other people spotted here and there in the hall—some couples, heads together. Suggest focus on the thin carpet peeling up at one corner, laying bare cement floor. Certain shabbiness so extreme it’s desolate—think that’s a G sort of thing to do, visually.

Her difficult friends became too difficult or too successful.

Drusilla at happening sort of downtown art party. She’s in foreground. One of her friends is there with her, sulking at her. The other is in the panel’s background, surrounded by a crowd of limp-looking hipster types, being lionized. Lot of room here to play with ’90s hipster accoutrements and decor in a G idiom. Want to stress elongation wherever possible, especially upward. A sort of pinched, unhealthy, looking-like-it’s-about-to-topple upward growth in all things, except Drusilla.

Parties confused her.

Okay, same party as before, different angle. The two friends still in view but off to the sides, one still being lionized, the other getting chatted up by a dubious type of some sex. Drusilla front and almost at center, looking toward us, face bleak. More with the ’90s hipster decor. Laces.

She became a waif.

Now Drusilla, still at the party, same place in frame, same clothes as ever—the sweatshirt, skirt and sneakers—but she’s sitting down with legs stretched in front of her. Still looking straight at us. Laces are distinctly longer than ever.

None of her poems were published.

Drusilla in her apartment, facing left—you have that, Kieran?—and an opened letter in her hand. It’s a rejection slip. Maybe a pile of them on kitchen table, but don’t overdo—sparseness important in all things with G. Apartment: sticks of furniture, little portable TV, Discman and scattered discs, scattered posters on wall for Lalique, Russian ballet, Nirvana.

She decided to work from home.

Drusilla trudging out of the office, with a box for her belongings in standard fashion. Box is almost empty, though. Coworkers look on grimly, supervisors frown, etc. Really she’s been fired, that’s the message.

She endured seeing her parents for the weekend.

The dinner table again, but with angle flipped—D now at panel left, the left end of the table, not the right. Parents older, quarreling harder than ever.

She found the thought of her journal burdensome.

Drusilla in her room at her parents’. Notebook and pen in foreground on table, Drusilla in background, to left, sitting by window. She’s trying to look out the window but can’t—her eyes are pulled unhappily toward the notebook.

Basic cable appalled her.

Downstairs in the dark, on a big couch. White glow from the screen. D on stomach, one leg folded so foot sticks up in air behind her; laces dangle a long way down. She has chin propped on hands and as she looks at the screen with a blankness that would appal one.

She found one of the pamphlets again.

Her room. She’s rooting about in a closet and finds a comic.

Without knowing why, she sat down to read.

Drusilla same position, same spot in panel as on page 8. On stomach, doorway behind her. Same clothes. But now she’s old and we see it: gray bits in hair, lines near mouth. One leg folded, foot up in the air behind her, and now the laces are spilling everywhere, a life of their own.

fin

And as before. Differences: her face isn’t propped up anymore, now it’s flat with the comic; shadows growing everywhere, especially among the folds and tangle of the laces; and in the background we have the fingers of a superhero gauntlet clutching the upper right side of the doorway, and the edge of a superhero cowl in view above the fingers, as if the creature were about to come and get her.

All right, that’s it. The professor just this instant texted to make sure we have all that about the superhero’s hand and cowl. “Job done, Hal, don’t worry :).” And Scarlett texted to say she likes, for the visuals, she likes a, quote, “Clean look, ex. Epileptic Bike, Rem Visit.” So there’s that.

Ali, you sent them the character profiles? All right, I’m off, thanks, looking forward to the magic I am sure you will—”

________

… collaborated with the actress and the professor to come up with an appropriately Gorey-like text. “The three of us developed a sort of electronic round robin,” Mr. Gaiman explained. “There was much buzzing of ideas back and forth via pocket devices.”

“The Extended Laces” recreates Mr. Gorey’s drawing style by means of digital techniques. Mr. Gaiman said, “They tell me we have some 15,000 signature lines and curves in the memory banks, and these are recombined.” He added, “It’s a painstaking process and, in the final analysis, really quite like an art.”

… early on the collaborators decided on updating the time setting, which for Gorey was typically Victorian or Edwardian. “Scarlett felt strongly that the 20th century was the new ‘creepy day of yore,’ to use her phrase,” Mr. Gaiman said. “Having spent so much of my life in that century, I could not say she was wrong.”

There is the possibility of a “syntha-Gorey” series, but no products are due to appear beyond “I am a Waif” t-shirts and sweatshirts. These feature the book’s heroine looking dejected and unsettling in the Gorey manner, and with overgrown sneaker laces. “We adamantly rejected the idea of marketing actual extended sneaker laces,” Mr. Gaiman laughed.

“There are these odd moments when one sees around corners,” Mr. Gaiman reflected when asked what attracted him to Mr. Gorey’s work. “I expect everyone has those. Mr. Gorey can in part be described as someone who was always seeing around corners, from one to the other, and who never learned how to stop.” He added, laughing, “If he wouldn’t find it presumptuous of me to say so.”

__________

Click here for the Anniversary Index of Hate.