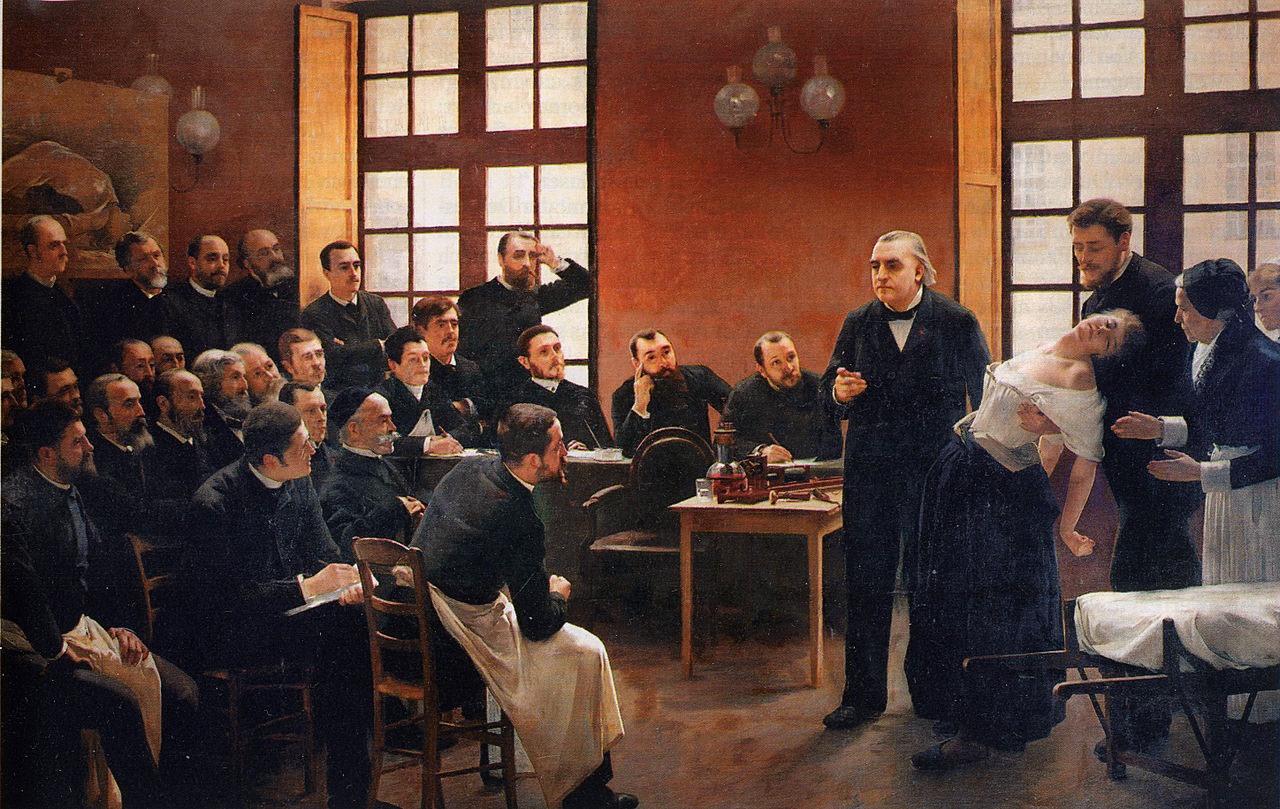

Over the last few weeks, Brooklyn’s Morbid Anatomy Museum has held a series of lectures on the historical context of hysteria and the often bizarre treatment of hysterical patients. In her first talk, Asti Hustvedt, author of Medical Muses: Hysteria in Nineteenth-Century Paris, described in fascinating detail the transformation that hysteria underwent as a result of the work of revolutionary neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot.

Charcot’s innovation was in re-characterizing hysteria from an intrinsically feminine form of madness to a neurological disorder like any other, capable of affecting both men and women alike. His research at the famed Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital in the late 1800’s was dedicated to studying and popularizing this new approach. Though they didn’t last long, his ideas about hysteria changed the way we thought about the human mind and gender, laying significant basis for the Freudian revolution just a few decades later.

Obviously sensing he was onto something, Charcot became known for putting on public events in which his hysterical patients would literally “perform” their symptoms for spectators. Charcot would personally select patients with the “best” symptoms to present, inducing the outrageous and shocking behavior through hypnotism and other quasi-occult practices. In this way, suffering from severe hysteria became a twisted form of celebrity.

The other night, with Hustvedt’s discussion fresh in my head, a provocative thought occurred to me. Charcot died in 1893, but his popularization of hysterical femininity as celebrity is still with us today. Inducing and performing hysterical symptoms form the basis of much of what we call “reality TV.” Nowhere is this more apparent than on ABC’s The Bachelor.

Put another way: Chris Harrison is the cultural reincarnation of Jean-Martin Charcot, and the Bachelor Mansion bears a striking similarity to the Salpêtrière, transported from nineteenth-century France to modern-day Los Angeles.

Let me explain.

Throughout this discussion, “hysterical” should not be construed in its common, disrespectful sense as simply an “out of control” woman. I’m sensitive to the fact that the concept of hysteria has been historically misinterpreted, abused, and put to obviously chauvinist ends.

s used here, “hysterical” is no insult. I am not attacking or judging the women on The Bachelor, and I also do not want to oversimplify them as people. My analysis represents simply one view of one aspect of their individual personalities.

I am using the term “hysteria” in its strictly psychoanalytic sense. Hysteria has been described in various ways by differing schools of psychoanalysis, but each of them seem to associate it with gender identity and the need for love.

Freud founded psychoanalysis based on his study and treatment of hysterical women, initially linking it to repulsion over childhood sexual experiences or fantasies. But over the years, Freud’s conception has been significantly refined.

For example, Hendrika Freud (no relation) describes the hysteric’s situation as this: I want to be loved, and how can I be loved? Slavoj Žižek formulates the hysterical question as a crisis of sexual-symbolic identity: What is it about me that causes you to say I am a woman? Darian Leader remarks that while men resent women’s bodies for not “speaking” to them, “hysterics are in general women whose bodies do in fact speak.” Christopher Bollas says that the hysteric lacks “an unconscious sense of maternal desire for the child’s sexual body –especially the genitals.” Melanie Klein links the feminine propensity for hysteria with jealous aggression and guilt that young girls often feel toward the maternal body.

But more specifically for our purposes, consider the view of French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan and his disciples. According to translator and practicing Lacanian psychoanalyst Bruce Fink, “the hysteric seeks to divine the Other’s desire and to become the particular object that, when missing, makes the Other desire…the [hysterical] subject constitutes herself, not in relation to the erotic object she herself has ‘lost’, but as the object the Other is missing.”

In other words, in the clinical Lacanian sense a hysteric is someone who cancels out a portion of her subjectivity in an attempt to become the object-cause of desire for some Other –in our case, the Bachelor.

Fink uses feminine designations purposefully. The history of psychoanalysis confirms that the historical association between hysteria and femininity is no mere anachronism or prejudice, but says something deeper about the relationship between culture and mind. Freud struggled for his entire life to divorce the two, but as noted by Juliet Mitchell in Feminism and Psychoanalysis, in the end he found himself back where he started: either something about hysteria was inherently feminine, or something about femininity was inherently hysterical.

In her book Mad Men and Medusas: Reclaiming Hysteria, Mitchell says, “every context which describes hysteria links it to gender –but not, of course, always in the same way. Historically, the various ways in which gender differences and hysteria are seen to interact should tell us something both about gender…and about hysteria.”

Thus, the paradox that so agonized Freud is at least partially resolved if we focus on Lacan’s hysterical structure. According to this view, the historical and structural link between hysteria and femininity is simply a result of the extent to which women have been asked to become objects of male libidinal desire across cultures and throughout time.

With this view in mind, let’s go back to our conception of The Bachelor as a modern version of Charcot and the hysterical performances of the Salpêtrière. It is not enough to merely remark that it is fun or interesting to see women acting hysterical on TV. The question, of course, is why are they acting that way?

The Bachelor’s formula is as simple as it is effective: anoint a Bachelor, round up a number of single women and put them in a situation in which they’re asked to “win” the Bachelor’s heart. Ask them to dedicate themselves fully to attracting an idealized Other, to transform their identities into the object-cause of desire for that Other –in other words, adopt precisely the Lacanian structure of hysteria.

If we follow Lacan, adopting the object-cause means canceling out at least some, and perhaps too much, subjectivity in the process. Bollas offers a similar view from the point of view of object relations theory, arguing that “the hysteric’s ailment, then, is to suspend the self’s idiom in order to fulfill the primary object’s desire…the hysteric’s primary object will be the object-in-waiting that the hysteric must find in order to be recast as the other’s object of desire.” As the show aptly demonstrates, adopting this psychic posture can have disastrous consequences for one’s emotional health.

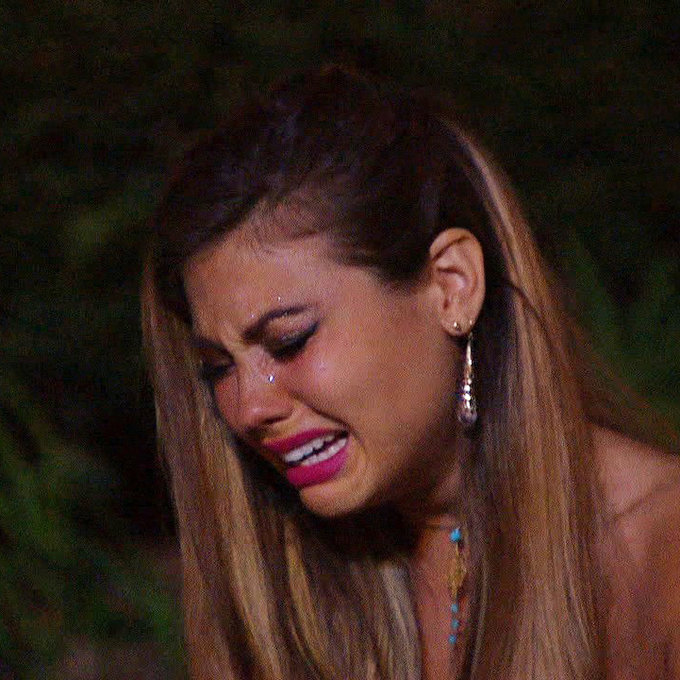

Thus, it’s no surprise that the institution of The Bachelor cultivates a smorgasbord of hysterical behavior in its contestant-victims: extreme jealousy, decentered identity, over-attachment to a functional stranger, histrionic behavior, and a lot, a whole lot of crying.

On this most recent season, no contestant modeled this account more consistently than Ashley I. Variously referred to as “the Kardashian” or “the virgin,” Ashley has displayed far and away the most frantic, bizarre, and irrational behavior of the season. She identifies closely with Disney princesses; she puts on ostentatious evening attire to sulk by herself and eat corn on the cob; she looks daggers at the other girls and adopts an annihilative stance; she runs away from the Bachelor in shame only to immediately reverse direction in desperation; each moment a prelude to tears. At her most passionately hysterical she becomes emotionally disintegrated, radically oscillating between sobs and bursts of dark laughter.

As indicated by her nickname, Ashley has never had sex and never had a long-term relationship. This fact, not altogether completely uncommon or extraordinary, seems to dominate the entirety of her personality.

But what is the value of Ashley’s virginity, and who values it? When Mackenzie hears about it early on, she expresses jealousy at the perceived advantage it gives Ashley. Virginity is frequently treated not as an aspect of Ashley’s personality so much as an object of libidinal exchange. We rarely hear what virginity means to Ashley. Instead, we hear Ashley worrying and speculating about what her virginity means to the Bachelor. (Compare Becca, also a virgin and the complete opposite of Ashley on this point.)

What I’m proposing here is that a major part of Ashley’s self is alienated in the Bachelor’s desire. Her sense of desire is one step removed from her, because it only accrues to her once filtered through the Bachelor’s desire.

Lacking the subjectivity necessary to own her own desire and instead devoted entirely to inhabiting the object-cause of the Bachelor’s desire, Ashley’s whole personality seems to be on the verge of collapse. That kind of dramatic tension is what makes Ashley and other Bachelor alumnae so compelling to watch. Love her or hate her, Ashley is a striking example of what happens when you structure too much of your personality around being the thing you think the other wants. All of us can relate to that.

Surprisingly, it wasn’t Ashley but Kelsey who actually experienced a collapse on a recent episode. Faced with the imminent possibility of being sent home, Kelsey forcefully confronted the Bachelor with an intimate story of personal loss. This was supposed to be her ace in the hole, a last-ditch gambit designed to ensure her desirability for at least a few more weeks.

But it didn’t work. Something told her that the Bachelor still wanted to send her home.

Ostensibly freaking out that he’s about to send a widow packing, the Bachelor panicked and canceled the night’s cocktail party in favor of standing outside on the balcony and staring into the bleak, abyssal night sky. Kelsey, suddenly overcome by anxiety, began rambling profusely to the other girls. Suddenly, she disappeared to a secluded corner of the mansion and was soon found lying on the floor, whimpering and writhing in anguish, in need of medical attention.

Some of the other women accused Kelsey of “faking” the attack, but that interpretation makes so little sense strategically that I am forced to assume the opposite. Whatever label you’d like to use, it appeared to me that Kelsey was experiencing extreme psychic pain at the moment.

Kelsey’s breakdown was about the hysteric’s relationship to rejection. Fink notes, “the hysteric constitutes herself as the object that makes the Other desire, since as long as the Other desires, her position as object is assured: a space is guaranteed for her within the Other.”

But what if the Other stops desiring? What if the Bachelor still wants to send you home? Psychically, the result is catastrophic: you disappear. As Žižek once put it, because “she is nothing but ‘the symptom of man,’ her power of fascination masks the void of her nonexistence, so that when she is finally rejected, her whole ontological consistency is dissolved.”

In other words, consider our understanding that becoming an object-cause of desire for the man involves a certain annulment of feminine subjectivity. Thus, when rejection approached and Kelsey’s feminine “mask” was pulled back to reveal the canceled subjectivity beneath, she suffered absolute existential devastation.

The “symptoms” (if the reader will permit me that word) suffered by Ashley and Kelsey may seem tame compared to the convulsions, somnambulism, and practically supernatural abilities of Charcot’s classical hysterics. But consider that some psychoanalysts and commentators have proposed that hysteria still exists today in concealed or muted form.

As Elaine Showalter discusses in her book Hystories: Hysterical Epidemics and Modern Media, things like chronic fatigue and multiple personality disorder may have roots similar to those of hysteria. Only fifteen years ago, Bollas called for a reassessment of hysteria in the psychotherapeutic community based on his view that hysterical patients are frequently misdiagnosed as borderline personalities.

But more broadly, hysterical behavior may be found anywhere a person –a woman, usually –is somehow motivated or forced to become the object-cause of desire for someone else.

Today, it’s easy and typical to think of hysteria as either a historical curiosity of the pre-Freudian and early Freudian world, or a chauvinist label applied to women considered “difficult” by patriarchal society. But as psychoanalysis and The Bachelor tell us, hysterical femininity is still with us –and it will be until normative concepts of femininity radically change, until feminine identity is allowed and encouraged to take up the position of sexual subject.

For more like this check out syvology.com and follow Tom on Twitter – @syvology