This first appeared on Comixology

___________________

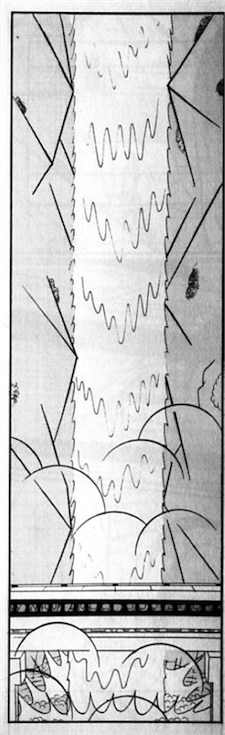

I first learned about Yuichi Yokoyama’s Travel — a wordless chronicle of a train journey — through a preview in the Comics Journal. The sample pages reproduced looked wonderful. An elongated rectangular image of a train racing in front of a waterfall particularly stuck in my head. The stark vertical of the fall was centered behind the stark vertical of the train, and both were contrasted with the diagonal slashes of rock in the moutainside, with half-circles of foam, and with the kinetic splatter of water striking water at the bottom of the page.

I first learned about Yuichi Yokoyama’s Travel — a wordless chronicle of a train journey — through a preview in the Comics Journal. The sample pages reproduced looked wonderful. An elongated rectangular image of a train racing in front of a waterfall particularly stuck in my head. The stark vertical of the fall was centered behind the stark vertical of the train, and both were contrasted with the diagonal slashes of rock in the moutainside, with half-circles of foam, and with the kinetic splatter of water striking water at the bottom of the page.

The elegance of the composition, the inspired simplicity of the stylization, the silent drama of the scene — it could almost be a Hiroshige or Hokusai print, if either of them had lived another century or so and adopted geometric constructivist modernism. So a whole book of that shit? Sign. me. up.

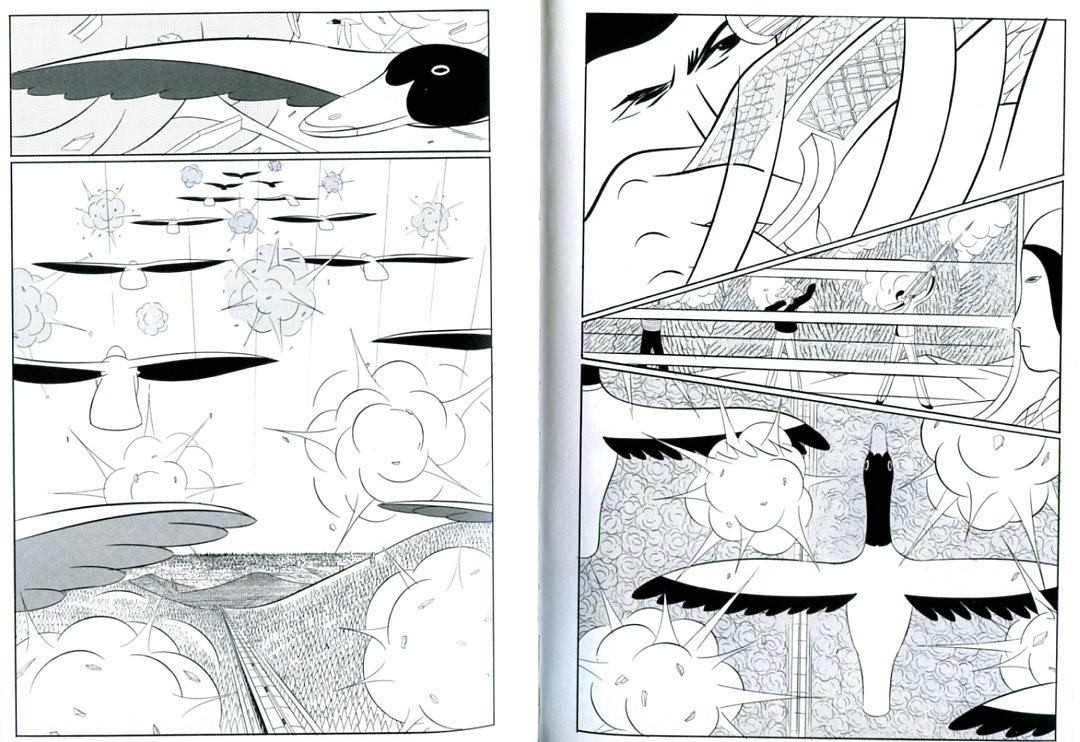

Probably I set my expectations too high. In any event, reading through the whole book for the first time ended up being something of a disappointment. I had hoped for page after page of stunning landscapes. Instead, the first quarter of the book is given over, not to spacious vistas, but to narrow, cramped interiors. The three anonymous protagonists begin their journey by walking in step through what seems to be the longest train on earth. It’s like being suspended in a Kafka dream; you go on and on, towards some indeterminate, unreachable destination. And just to make the suspended tedium more disorientingly intolerable, random details leap out at you, weighted with heavy symbolic importance.

Here’s a panel devoted to a row of chairs. Here’s one of a passenger with oddly patterned clothes, even more oddly coiffed hair, and a face from which the ruthlessly angular, schematic stylization has removed any lingering trace of emotion. Much of the time I couldn’t even tell what was happening. A group of uniformed men sit in rows in an upper-berth; a camp-fire is lit; a space-station floats overhead — is this all happening in the train?

Even when our peripatetic protagonists do finally sit down and open the window shade, allowing us to see what’s happening outdoors, there often seems to be some key missing. Why are those white hexagons spread across the panel? Are those two men painting a sign — and if so, why is the sign entirely black? What are we looking at, and from what perspective? Even though there were no words, I felt like I needed a translator. If I were Japanese, presumably, all these references and odd in-jokes would make sense. What I needed, it was clear, was an extensive set of foot-notes.

And sure enough…I reached the conclusion, was duly befuddled by the end (are they at the seaside there?), turned the page — and ta-dah! Brief end-notes are provided keyed to just about every single page! Yay! Now all will be explained!

Well…yes and no. Yokoyama’s annotations do occasionally provide some straightforward logistical help: for instance, it turns out that the campfire was on a television screen in the train, rather than on the train itself. In most cases, though, the author seems as baffled as I was. He writes for example, that the uniformed men on the second level of the train are “tourists…dressed like soldiers. The symbol on their helmet is unlike those belonging to any currently known nations.”

In other words, they’re not mysterious because I’m from a different culture and don’t know what’s going on. They’re mysterious because they make no sense. What are they doing there? Why are they dressed like that? Why, later, do they all get off at a train station in the middle of nowhere? Yokoyama doesn’t know either. It’s just one of those things.

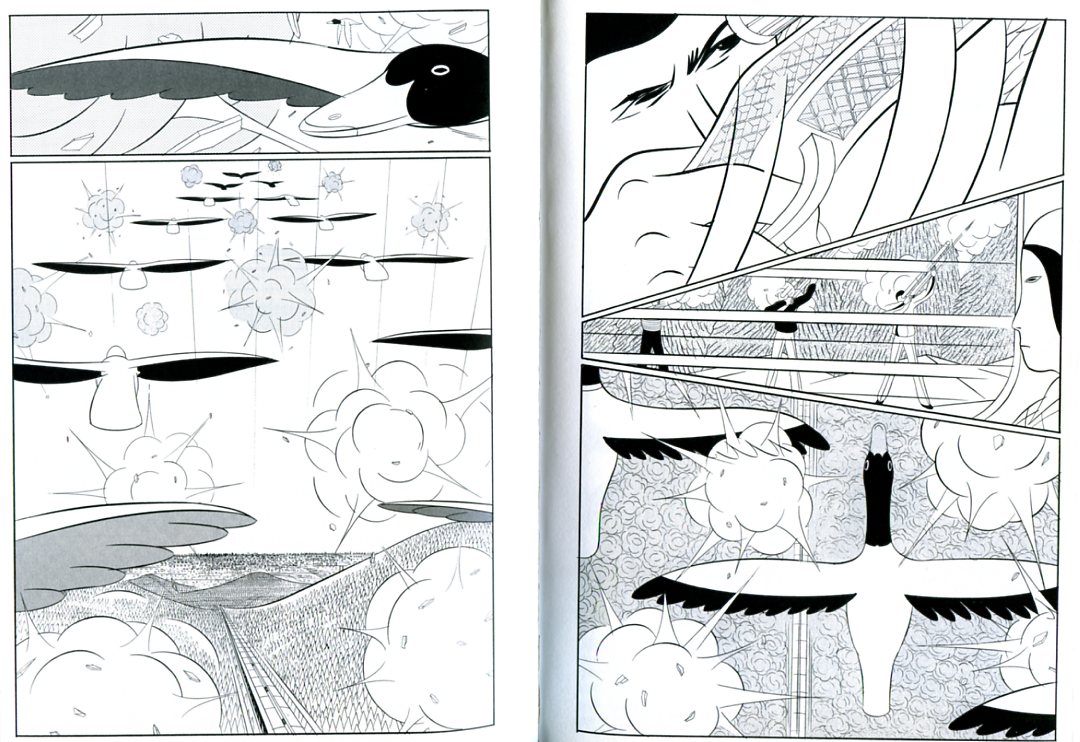

Yokoyama had wrong-footed me. I was looking for realism, and so I found the epistemological uncertainty frustrating. But the book isn’t realism — or not exactly. It’s pomo; Yokoyama’s tongue is in his cheek the entire time. Take the scene of ducks flying over the plane as hunters shoot at them. The footnote points out that the hunters all miss, and indeed, you can see the ducks traveling in a perfect V, not even disturbed by the shells exploding in pristine, regimented bursts all around them. The demands of narrative (somebody shoots, somebody hits) are sacrificed, with a wink, to the exigencies of layout. It’s as if the hunters and the ducks are not adversaries at all, but part of some single great mechanism, controlled by one guiding hand. As, of course, they are.

The book, in other words, actually revels not in realism, but in artificiality. It’s virtuoso performance. The motion lines throughout, for instance, are emphatic and solid, drawing attention to themselves as elements of the design. As a result, every movement is like an explosion; the two page sequence depicting one of the travelers taking out and lighting a cigarette is choreographed with all the delicate finesse of a Jack Kirby Thing-vs.-Hulk encounter.

Or, as another example, there’s one page which opens with an extreme close-up of a toothed maw. In the next panel we pull back dramatically to see that the mouth belongs to a wild dog, now only a tiny silhouette on top of a towering rocky outcrop, howling as the train races by beneath it. Then, in the next panel, we’re looking at the train through the gigantic horns of a moose…and then we pull back again to the perspective of the train itself, and watch the moose passing by far below. The movement from close-up to way down to close-up to high above is not natural or intuitive, but insistently self-conscious.

The thing is, there is a sense in which, when traveling, insistent self-consciousness is natural. When taking a trip , I, at least, sometimes have this sense of alienation, of hyper-sensitivity. When you’re knocked out of your routine, it’s hard to tell what matters and what doesn’t, and so everything — the man opening a book, the light flickering off a pen, the patter of water on the roof — becomes the most important thing in the world, equally vital and equally mysterious. It’s an experience analogous to Emerson’s description of the “transparent eyeball” — a humorous, grotesque, and sublime sensitivity, which feels, in its otherworldliness, almost inhuman.

Emerson’s philosophy was influenced by Buddhism. His all-seeing, all-receptive eye is similar to the roving eye of the Japanese woodblock prints, where landscapes are viewed sometimes from a mouse-level vantage, looking past a horse’s foot, and sometimes from far up in the sky, behind a bird’s wing. This perspective, which is everywhere and nowhere and which finds beauty in all things is, at least by implication, divine.

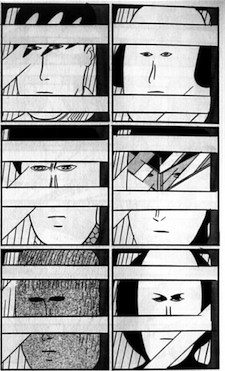

In Yokoyama’s work, too, the viewpoint swoops and swerves, now with a skier on a high mountain pass, now underneath the train. There is certainly a celebratory, joking tinge to Yokoyama’s impossibly mobile camera. But there is also something ominous. In one sequence from the book, our protagonists’ train passes another going in the opposite direction. A whole page is devoted to the faces on the other train. They are shown in four tiers of three blocks each; all are streaked with violent motion lines; all are the same shade of grey as the window frame, all stare intently outward at the viewer. The scene is oddly disturbing; the repetition of the faces, the repetition of the expressions; the lines going through them, the grid — it’s dehumanizing, as if the faces are not people at all, but manikins, or masks. Yokoyama’s note to the image reads:

In Yokoyama’s work, too, the viewpoint swoops and swerves, now with a skier on a high mountain pass, now underneath the train. There is certainly a celebratory, joking tinge to Yokoyama’s impossibly mobile camera. But there is also something ominous. In one sequence from the book, our protagonists’ train passes another going in the opposite direction. A whole page is devoted to the faces on the other train. They are shown in four tiers of three blocks each; all are streaked with violent motion lines; all are the same shade of grey as the window frame, all stare intently outward at the viewer. The scene is oddly disturbing; the repetition of the faces, the repetition of the expressions; the lines going through them, the grid — it’s dehumanizing, as if the faces are not people at all, but manikins, or masks. Yokoyama’s note to the image reads:

“All of the passengers in the passing train are looking this way. Whether the naked eye could actually instantaneously register these individual faces is questionable, but this scene may not represent a human perspective at all.”

If it’s not a human perspective, then what is it? And is it beneficent or not? The ukiyo-e artists created individual images; magical windows that captured an instant. What’s vibrant about a Hokusai print is that it captures a moment; there’s a sense of time stretching before and after which energizes the image, giving it power and grace. By showing a sequence, on the other hand, Yokoyama’s world is less vibrant, more dead. To see as God does, for a moment, is exhilarating; to have that vision extended becomes oppressive. Yokoyama’s geometries, his angular series of iterated, impossible scenes, suggest a kind of literal deus ex machina — a deity made out of clockwork.

In the last pages of the book, the three travelers march again, moving in eerie unison out of the station, across a field, and to the shore. There they stand in their aggressively patterned shirts before a sea so turbulent it can be apprehended itself only as surface patterns of spray against rocks, the depths barely visible as smaller splashes of design which suggest a fathomless and unperceivable distance. Space flattens out, until inside and outside, interior and landscape, become one. Self-consciousness is the consciousness that the self slips through your fingers; it is nowhere, or everywhere, part of a design that moves forward and backward through time. The image of man and universe in eternal synchronization is both devotional and sinister. Read and re-read, Travel seems less like a journey than like a single, unyielding now.