Editor’s Note: This is the week my book, Wonder Woman: Bondage and Feminism is released. I’ve put together a week-long roundtable to celebrate.

_________

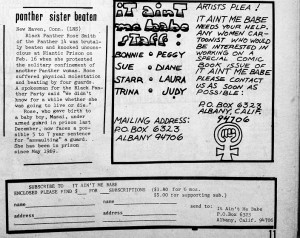

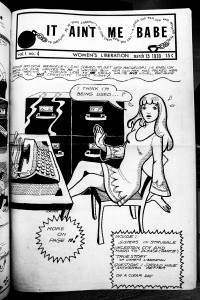

Longtime comix artist Trina Robbins is also one of Wonder Woman’s biggest fans; she’s talked and written on numerous occasions about her love of the Marston/Peter comics in particular. I interviewed her after she’d read (at least some of) my book.

Trina: So you should know I’m only in the middle of your second chapter. It’s a bit of a slog. You do have a good sense of humor and I like some things about your writing. You just so over-analyze that it just becomes a slog.

Noah: (laughs) Well, that’s the academic thing, you know.

Trina: I know. Thank god I’m not an academic.

Noah: All right…well, could you talk a little about what you like about the Marston/Peter comics?

Well, as a kid, I foudn the mythology extremely liberating. And I’m still into the mythology. And of course people like Brian Azzarello obviously knows kowing nothing about mythology or just doesn’t care.

I mean, for me, Jewish girl, brought up in a not super orthodox home, for me Judaism was very boring. At the synagogue they spoke Hebrew, which I didn’t know. One God, and this very boring and very patriarchal guy with a white beard. I didn’t like that at all. And I couldn’t relate to it. And Wonder Woman had goddesses. A whole pantheon of gods and goddesses. The gods weren’t particularly nice, but the goddesses were wonderful. And this was so liberating for me as a kid to read this. It was almost as though Marston had given us permission to believe that there was something other than the patriarchal bearded guy.

And also just the concept of Amazons. I think I was introduced to the concept of Amazons in Wonder Woman. This whole tribe of beautiful women alone on an island, no men. You have to understand that as a girl…boys were threatening. Not all boys, I had some nice male cousins. But in general they were threatening. They were bigger than me, and they tended to be a little nasty — women were wonderful. I grew up during the war when women wore bright red lipstick, and most of the guys were off at war anywhere. And women were much more interesting. It’s interesting because I’m totally heterosexual, but these are just the feelings I had.

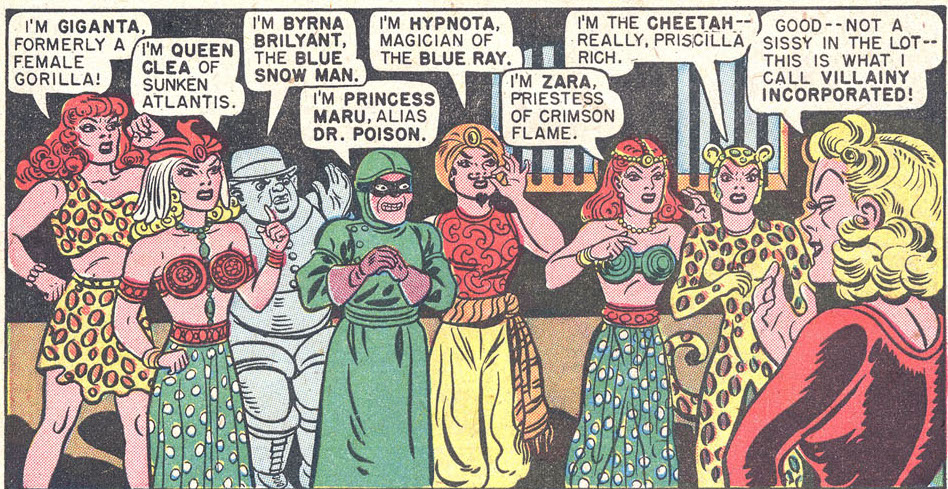

An island full of women in pretty little dresses and they were all beautiful. It was just a wonderful thing to me. And as for the rest, what little girl doesn’t want princesses. She was an Amazon princess. So that’s what I saw in it. I saw stories in which women are all the ones who are the active ones. Not just Wonder Woman, but the Amazons and the HOliday girls, they’re active participants, they all fight the bad guys. It was wonderful for me.

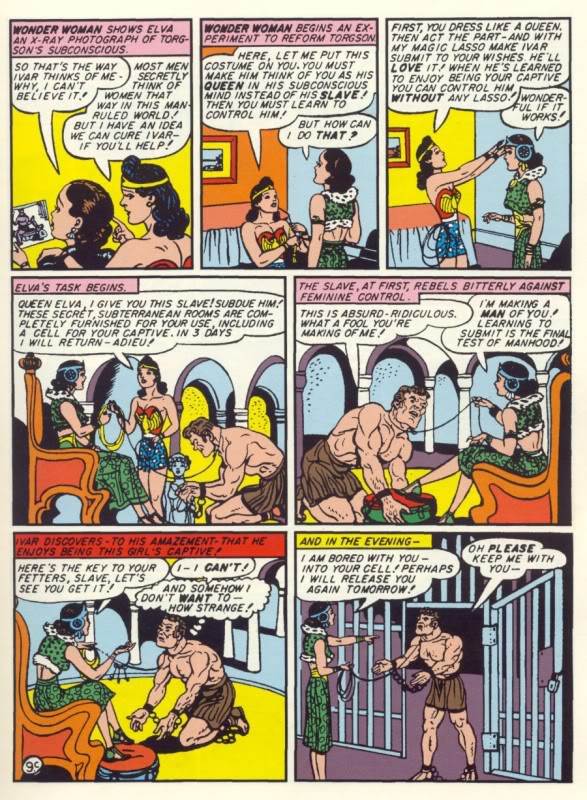

Noah: One of the things we’ve disagreed about before is on how much bondage there is in the comics, and how important bondage is in them.

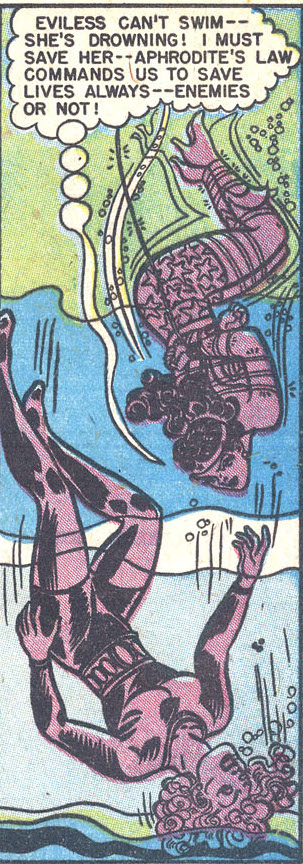

Trina: Well the thing is, as a kid I didn’t even notice the bondage. It went totally over my head. Obviously there are people who noticed it. I think they tended to be grownups. You know, like that soldier who wrote to Marston [about how he was a bondage fetishist and therefore loved Wonder Woman.] But I didn’t see it. Or if I did see it, I looked at all the other comics. It was traditional in Golden Age comics for people to get tied up. I’ve just been scanning in Girl Commandos drawn by Jill Elgin, and they always get tied up in each comic.

Noah: Tim Hanley recently counted how much bondage there was in Wonder Woman, and found it was more than in most other comics of the era…

Trina: Obviously he’s right, because he counted, and numbers don’t lie. But I didn’t see that, I can tell you. Because in all the other comics people got tied up too, and I didn’t count!

Noah: I’m curious about the lesbianism in the comics and what you think about that.

Trina: Not many people have talked about that except for Frederic Wertham in Seduction of the Innocent. And he’s a riot. The connections he makes with Holliday equals gay are just hilarious.

But of course there are hints of lesbianism. But for me it was more about women interacting with other women. In the British girls comics it’s always girls saving other girls. But if you look at the comics for the same period for the same age, it’s always the love triangle. Betty and Veronica fighting over Archie. It’s almost as though they’re trying to show, look we can do comics about girls, but don’t worry, they’re not lesbians.

Noah: Marston was not worried about that.

Trina: But as a kid I just thought, how wonderful. How wonderful, a woman’s world.

Noah: Marston would be quite happy with that, I’m sure.

I wondered if you had thoughts on the relationship between Olive and Elizabeth and Marston?

Trina: Well, definitely they were polyamorous. And I think it’s pretty probable that Elizabeth and Olive were lovers.

It’s very funny because…Spain Rodriguez, I don’t want to speak ill of the dead, and he was a dear friend of mien — and he’s still a dear friend of mine, even though he’s no longer with us. But he was so funny, he used to say, “See, he lived together with two women!” As though, ha, ha, he wasn’t a feminist. And I was like, Spain, if Susan would let you, wouldn’t you like to live with two women?”

Noah: It wasn’t like he was living with them without their consent.

Trina: Exactly.

Noah: I presume…I mean they lived together afterwards. It doesn’t seem like it was just…

Trina: They weren’t doing it just for him, or they would have moved away after he died. Of course.

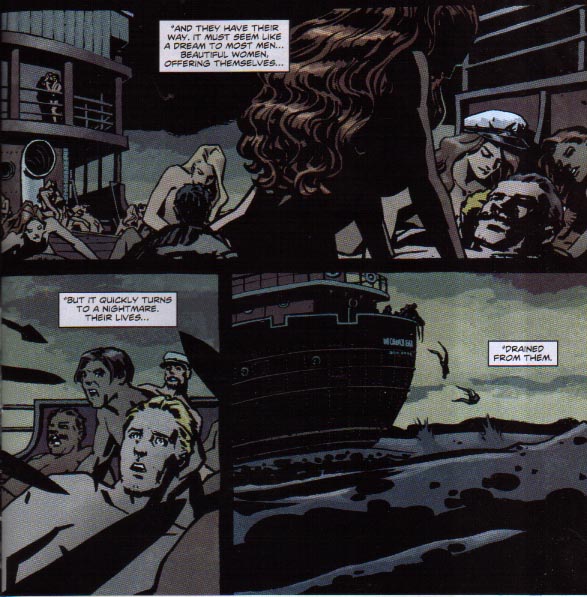

Noah: I know you had harsh words for the Azzarello run on Wonder Woman…

Trina: It’s not just…he’s so arrogant! He’s so fucking arrogant. There was this one shot, it was a Wonder Woman run shot which was about Wonder Woman as a girl. It was intended to be some kind of parody of the Stan Lee comics of the 60s. Which of course doesn’t make sense anyway, since it’s a DC character and it’s completely different. But he doesn’t even know as a writer and a historian — he’s trying to make it old fashioned, so he has Princess Diana use the term “shan’t.” Well, by 1955, no one was saying “shan’t”.

And then in case you thought that he was not trying to be an arrogant asshole…you know how the old Marvel comics, Stan Lee would give everyone nicknames like “Jolly Jack Kirby.” So he signs his name as Brian “Kiss My” Azzarello.” That’s his statement. The innermost circles of Hell for him.

Noah. You really didn’t like his Wonder Woman run.

Trina: (laughs) You could tell.

I loved what Gail Simone did. Her white gorillas were the equivalent of the Holliday girls I just loved what she did.