Imagine if George W. Bush had been forced to stay in office till he had personally gunned down Osama Bin Laden. Or if Obama can’t leave till he bags his own arch-nemesis, Edward Snowden. What would that sort of megalomaniacal mission do to a guy?

It turns him into Batman.

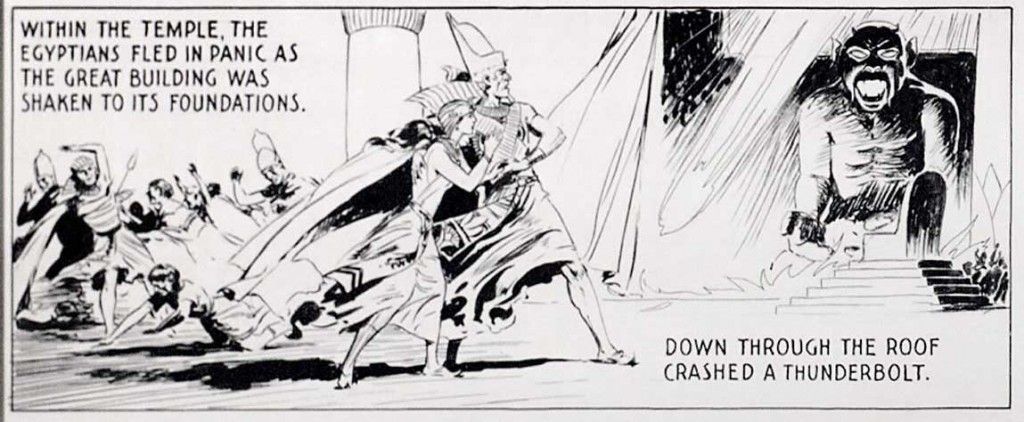

“The spiritual theme of Batman,” writes E. M. Forster in Aspects of the Novel, “is a battle against evil conducted too long or in the wrong way. Criminals are evil, and Batman is warped by constant pursuit until the knight-errantry turns into revenge.”

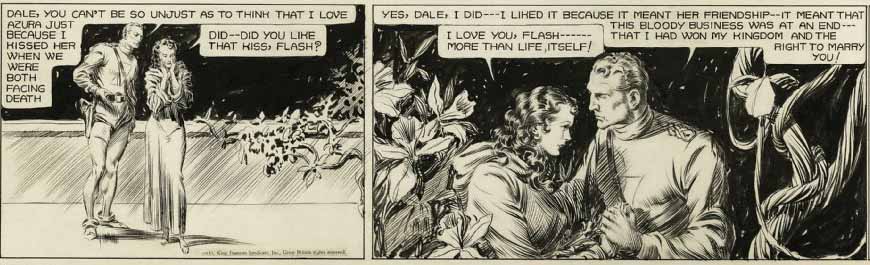

Okay, I’m lying. Forster wrote that about Meville’s Moby Dick. But swapping Batman for Captain Ahab (or Bin Laden for that big fat whale) shows how bizarrely time works in comic books. Or doesn’t work. Superhero time is both frozen and endlessly moving.

Batman’s parents were gunned down “some fifteen years ago.” That origin fact was first printed in 1939, so that meant 1924. Today it means 1998. Because Batman’s parents were always gunned down some fifteen years ago. That point in time is constantly shifting. Unlike U.S. Presidents (who, according to medical researcher Michael Roizen, age twice as fast while in office), Batman can’t age.

If his “war on criminals” were roped to real time, his character would become as monstrous as Melville’s obsessed whale-hunter. Batman is already carrying an unhealthy dose of the Captain in his utility belt, but without a time frame defining just how warped his mission might be, he skirts to just this side of self-annihilating megalomania. (Plus, according to E. Paul Zehr, he would only last three years—less than a Presidential term, but the same as an NFL running back. The human body can only take so much punishment.)

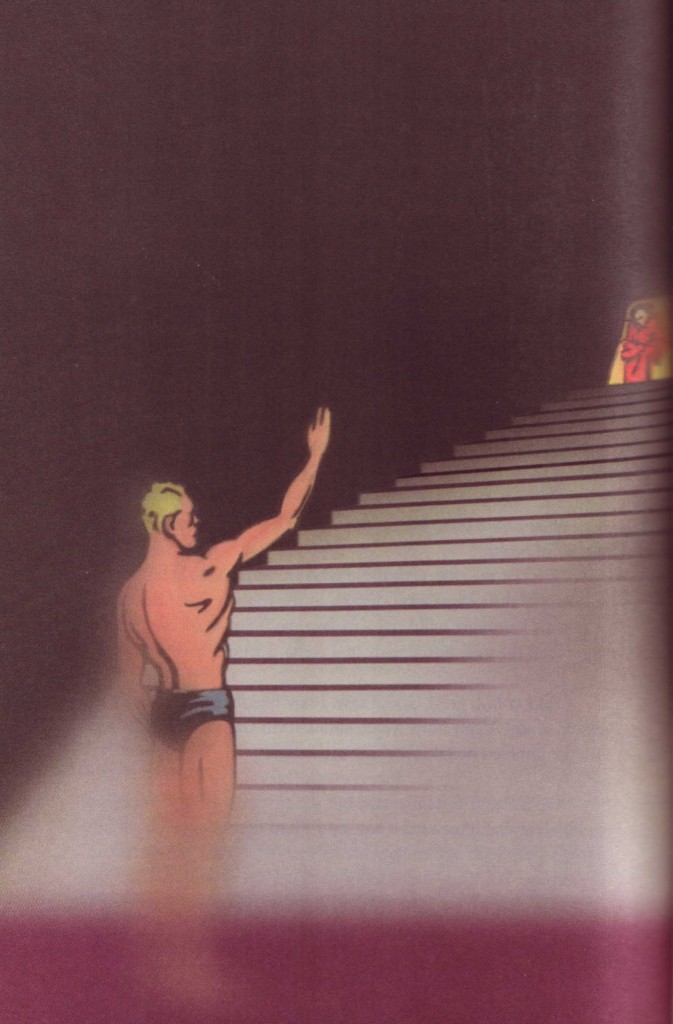

Superman lives in the same continuous present. In his 1962 essay “The Myth of Superman,” semiotician Umberto Eco analyzes that “temporal paradox.” (I’m not lying this time; Eco really does analyze a comic book.) Superman is mythic in the timeless, archetypal sense, while also adventuring in our “everyday world of time,” and so the “very structure of time falls apart.”

That requires some fancy story-telling. Eco particularly admires how DC created a dream-like climate in which the reader “loses the notion of temporal progression.” We keep looping back into Superman’s personal timeline to hear previously untold tales. When Superman co-creator Jerry Siegel was hired back to DC in 1969, his first assignment was a six-page script explaining how Clark Kent got hired at The Daily Planet. Siegel covered that in two panels back in 1938. The newspaper had been called The Daily Star then. No one minds the change, or even notices. It’s just part of the continuous dream.

At Timely (Marvel’s old name), superheroes refused to loop backwards. When the Human Torch reignited in 1954, it was 1954 for him too. He’d fought Nazis in the forties, and now he was fighting Commies in the fifties. We even got an explanation for his period of absence (he went supernova in the desert), and an explanation for his return (hydrogen bomb testing reawakened him). Timely time always marched forward.

Over at DC, superheroes only battled pretend villains, ones that bore little or no relationship to current events. Pick up an issue of Action Comics during World War II, and except for a patriotic cover endorsing government bonds, you wouldn’t have known there was a war on. Ditto for the Cold War. The Man of Steel never faced the Iron Curtain. It would have pinned him to real time.

Superheroes would have continued happily to inhabit their private, timeless planet, had Stan Lee not come along to screw things up. Like their Commie-bashing forebears, Marvel’s Silver Age heroes were cold warriors. They were literally timely. Rather than avoiding chronological progression, Stan Lee highlighted it. His captions even recapped past issues to nudge forgetful readers. No more continuous dream. Naptime is over.

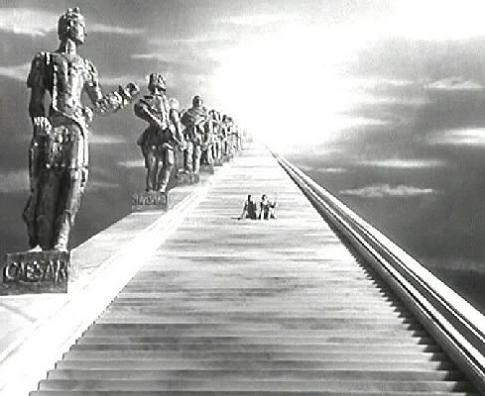

And that created new problems. If tethered to our world, superhero time eventually falls out of sync. Batman’s “some fifteen years ago” is very different from the Fantastic Four’s origin-producing rocket launch. Parents can get gunned down in any decade. The Waynes weren’t scrambling to beat the Commies. The Space Race isn’t a mobile pocket in time. That’s 1961. That will always be 1961.

That’s also one of many many reasons why the 2005 Fantastic Four film didn’t work—and why I’m less than hopeful about the reboot now in production. No Space Race, no reason for Reed Richards’ botched radiation shields. The guy’s supposed to be a genius, but his girlfriend is shouting: “We’ve got to take that chance, unless we want the Commies to beat us to it! I – I never thought that you would be a coward!” The historical context is everything.

DC held out as long as they could. But by 1968 they ended their isolationist policy and introduced Red Star, their first Soviet superhero. California Governor Ronald Reagan made his first comic book appearance the same year. (Marvel wouldn’t notice him till he made it to the White House.) Because of Timely, superheroes had to stop reliving the same Daily Planet headlines. The planet was revolving daily whether they liked it or not.

I was on the other side of the planet, in Melbourne, Australia, when I read the Herald Sun headline: “Osama bin Laden is dead, US President Barack Obama confirms.” That was May 2011, so the U.S. government’s knight-errantry lasted just under a decade. The photo showed flag-waving college students cheering outside the White House lawn. Some of them would have been reading comic books when the World Trade Center came down. Bin Laden was their Hitler, their Lex Luthor, the monster breathing under their bed all night.

Imagine if we hadn’t caught him. Imagine America if that decade had drifted on some fifteen years. Or if September 9, 2001 weren’t a fixed point, but a whale-sized weight dragged forward by every new, time-warped President. Imagine a battle against evil conducted too long or in the wrong way. What happens to a country under a never-ending Patriot Act? To a government locked in a constant pursuit of surveillance? The national psyche can only take so much punishment.

A word of comic book advice to President Obama regarding whistle-blower Edward Snowden:

Time to move on.