This is part of a roundtable on The Drifting Classroom, and also part of the October 2011 Horror Manga Movable Feast.

________________

Adrift/ Cut the Cord

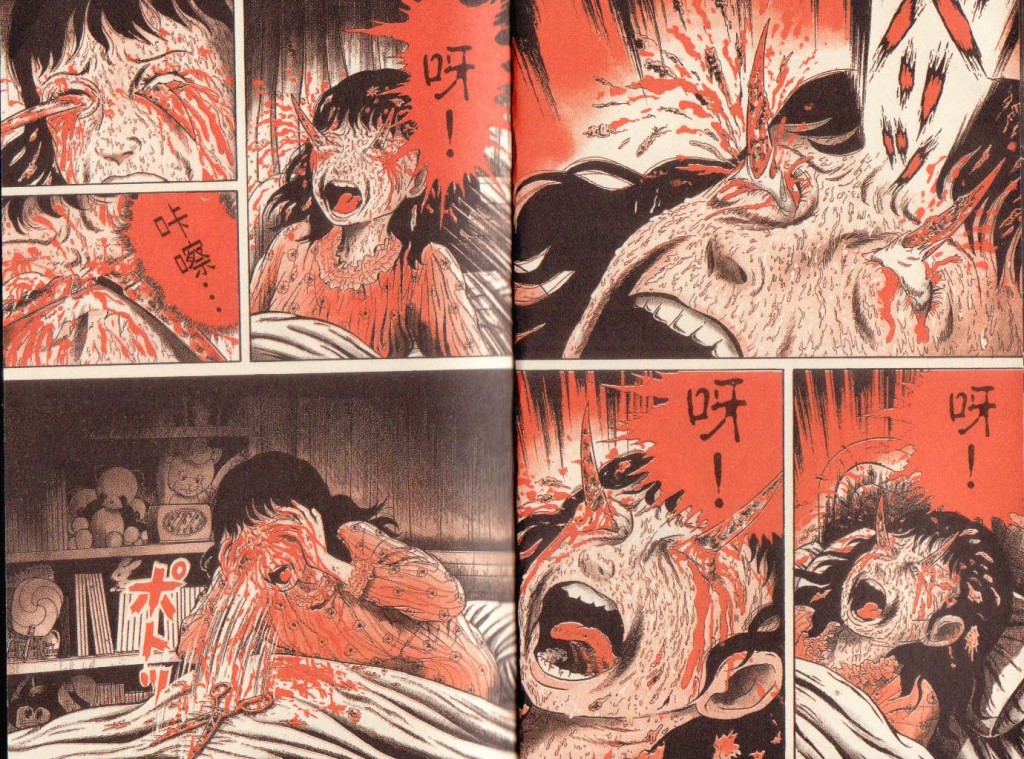

Hunger. Butchery. Transformation. An impossible situation.

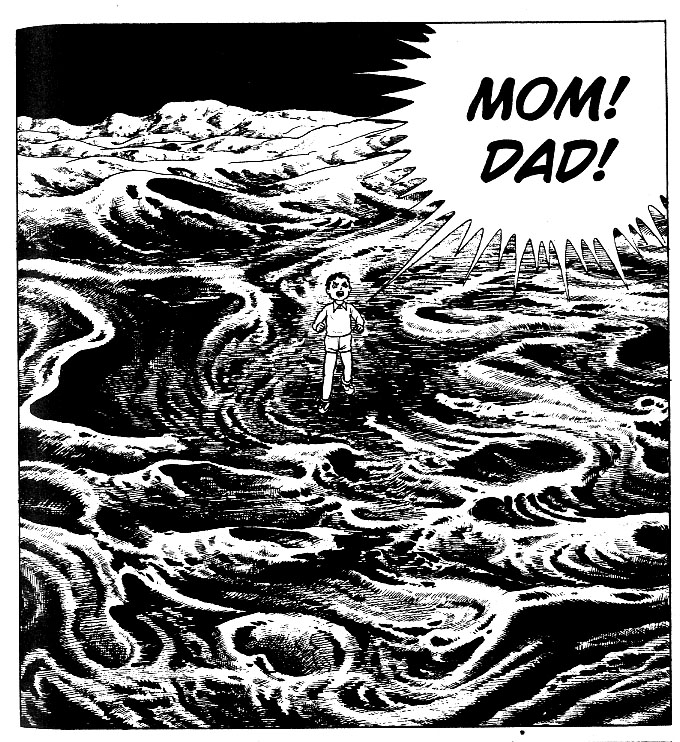

A world without sense, without purpose or direction. Children adrift with no home, separated permanently from that bit of comfort and warmth that protects, that shields from the unknown. Slaughter, thirst, dirt and maggots and refuse and decay and no order, not at all.

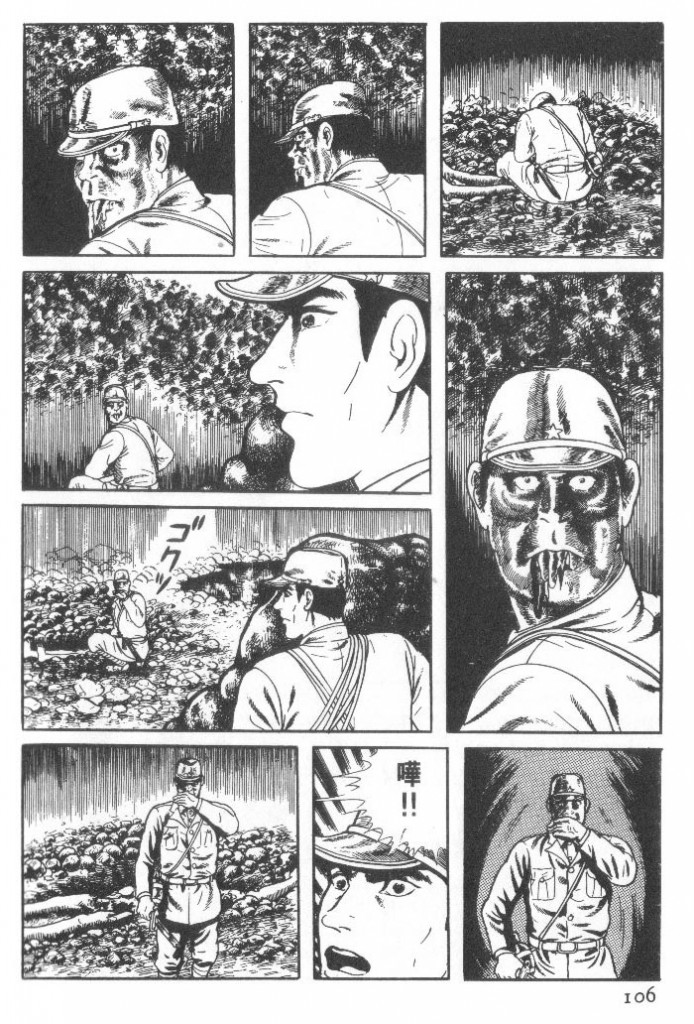

The Drifting Classroom was originally serialized from 1972 through 1974 in the pages of Weekly Shonen Sunday magazine. Ostensibly aimed at an audience the same age as the story’s chief protagonists, the Drifting Classroom finds an entire elementary school mysteriously transported to a horrific landscape of death and waste where they must try their best to survive. The few adults that have been transported are, at best, helplessly arrogant and stupid, unprepared for the unrestrained, unordered world to which they have all been delivered; at their worst, the adults are crazed thieves and murderers who must be dispatched to prevent even more carnage.

The most resourceful of these children is Sho, a sixth grader of extraordinary leadership who struggles to create a small bit of social order in the complete disorder in which the children find themselves. Initially these are very small victories—coordinating the children to fend off an attacker, or equitably distributing a small amount of food. But even as the obstacles mount, Drifting Classroom begins to suggest that more may be possible with Sho, that there may be some reason for these refugees to hope for some resolution, for some bit of survival.

Bath Time/Lots of Fun/Helpless

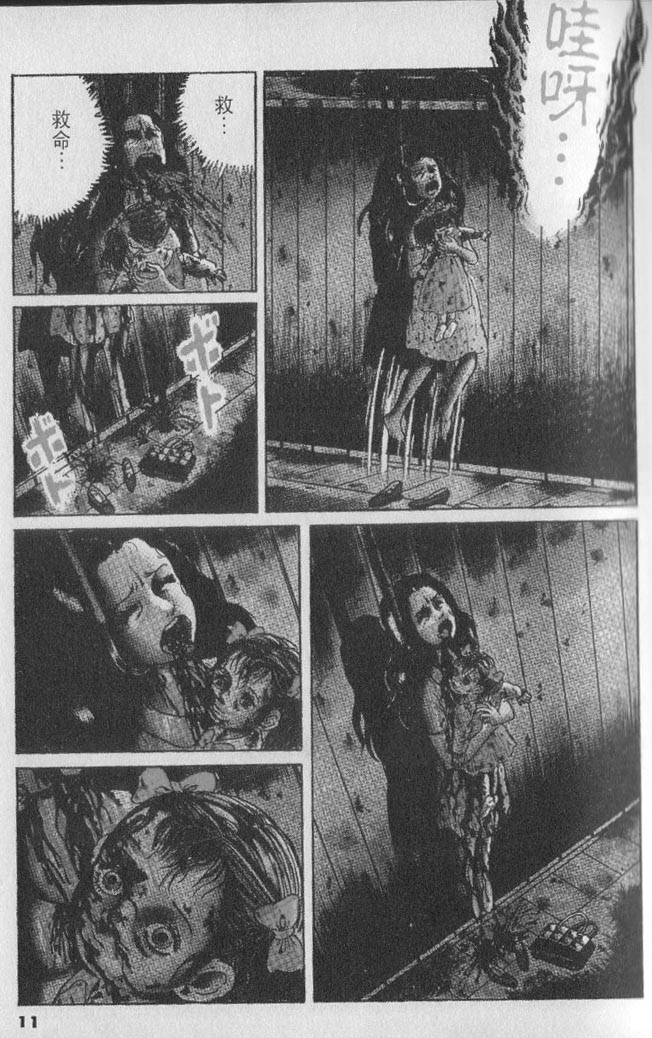

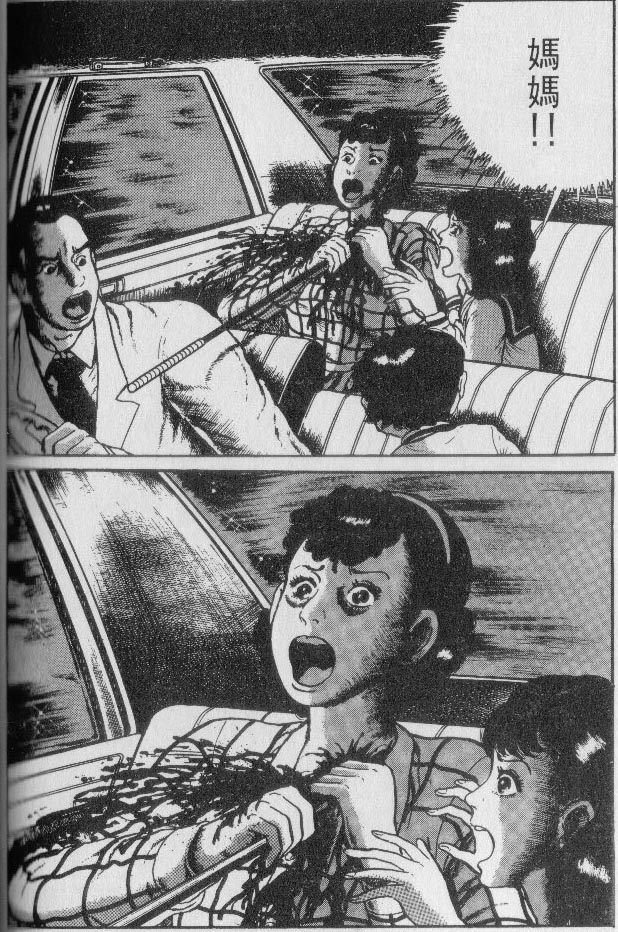

Having all been children once, you would think that no adult needs the reminder—but to be a child is to be completely helpless in the face of a casually cruel world. A parent’s primary responsibility is to protect, and his second, to nurture—to help her child take those first tentative steps towards navigating the world. The first social structures that most children encounter in their lives are the ones created by their parents—their one-on-one relationship with their parent, the close circle of the immediate family. And a child can grow more confident and skilled in this limited environment, assuming a certain amount of stability and safety.

But for most children the world of the family is not the whole world forever, and the child will eventually encounter social situations and structures that are new to him, that may seem completely bizarre and arbitrary. At the age of two I was baby-sat daily by a woman down the street who had a large family. It seemed like a very natural thing for me to be taken into this family every afternoon, like some extended version of my own with different faces and different voices and different toys. But soon after my fourth birthday I began attending a Methodist daycare full-time while both my parents were at work, dozens of children and staff in an old, poorly-lit building in an unfamiliar part of the city. The adults were strange and distant and unknowable, the other children too numerous to be distinguishable from each other. I ate lunch by myself, sat in the corner during play times, was terrified of getting something wrong and of the inevitable retribution. One lunch time I bent a spoon until it broke, and, terrified of discovery, hid it beneath my chair before dumping my tray into the dish washing receptacle. Another lunch time I felt nauseated, and tried to get out of my assigned task of passing out napkins to the whole group. I was told to do my part, and so I continued, until I vomited on the napkins and myself, at which point I was taken to a nurse and sat in a corner alone with a glass of water and a fresh paper towel. All this anxiety, it seems, was justified. My parents told me years later that they had given me a bath one night only to find that I was trying to hide my back, which was covered with long bloody scratches, the apparently accidental work of one of the day care teachers, who had instructed me not to tell my parents about the mishap.

I don’t think that any of these events are unique. Their ubiquity is the point—that, to a child, the world is a confusing, dangerous, and at first, unknowable place, and that an adult is a capricious monster capable of any manner of harmful, arbitrary action.

No Francis Bacon/Vegetarian

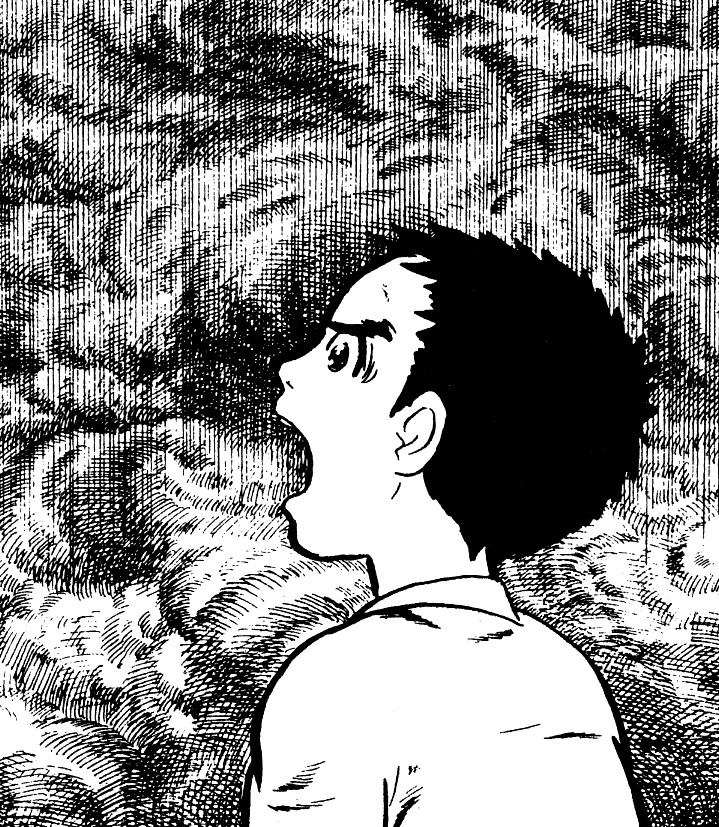

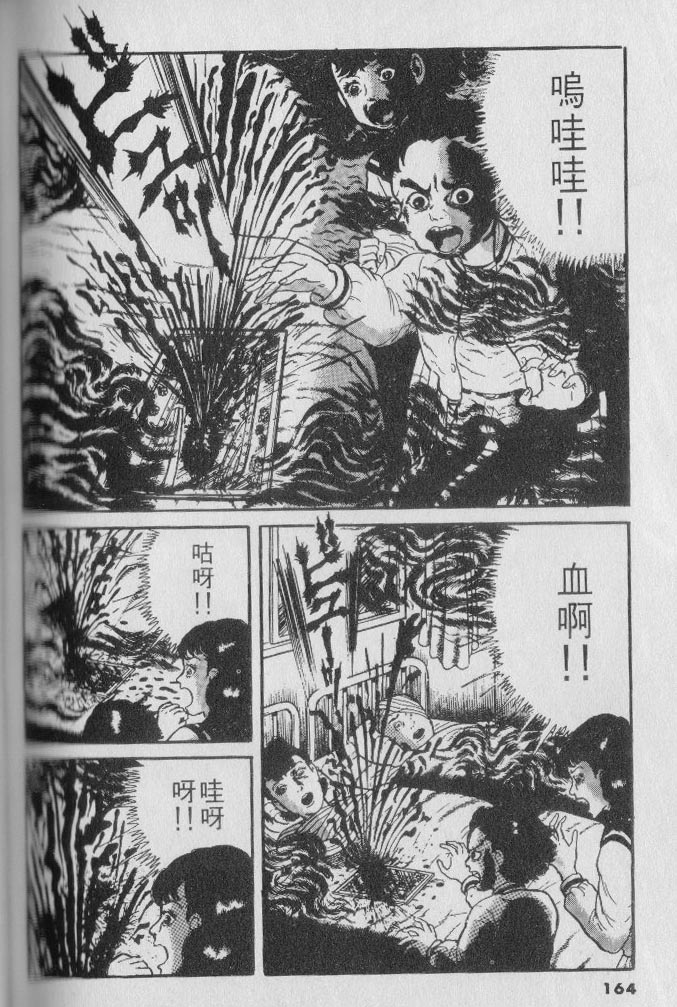

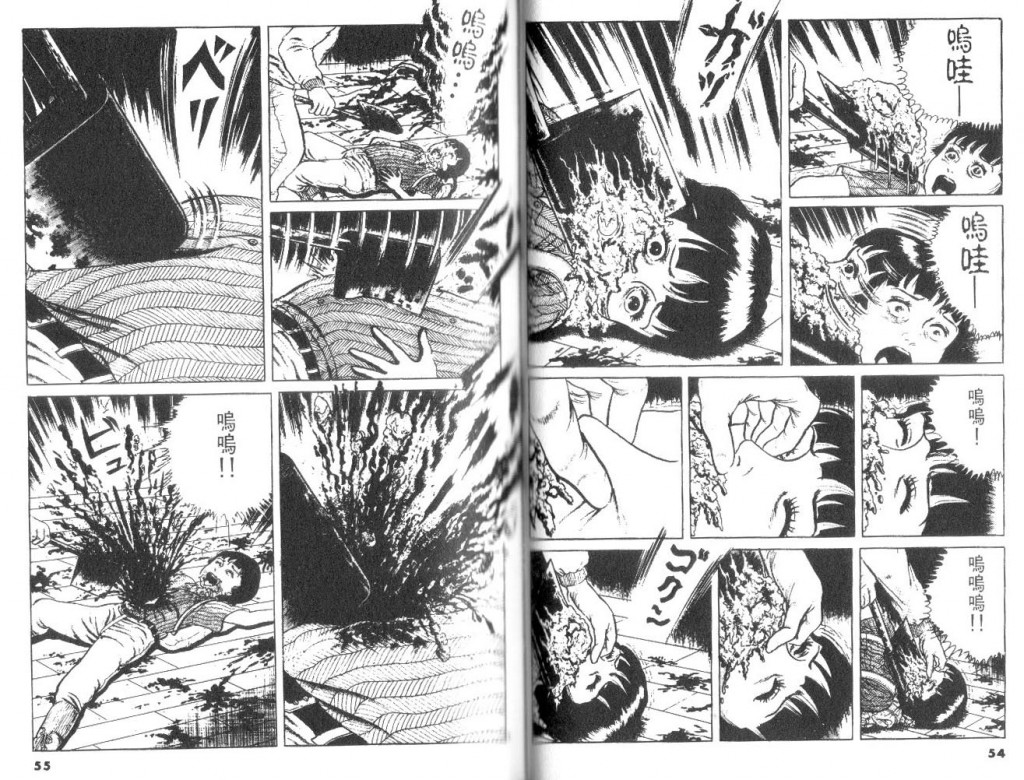

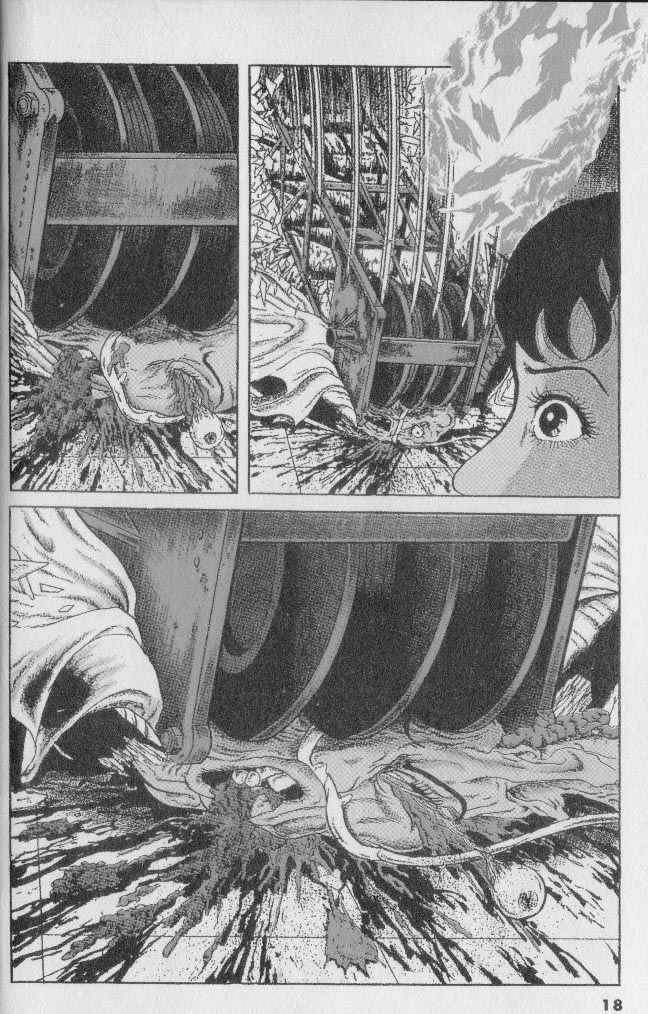

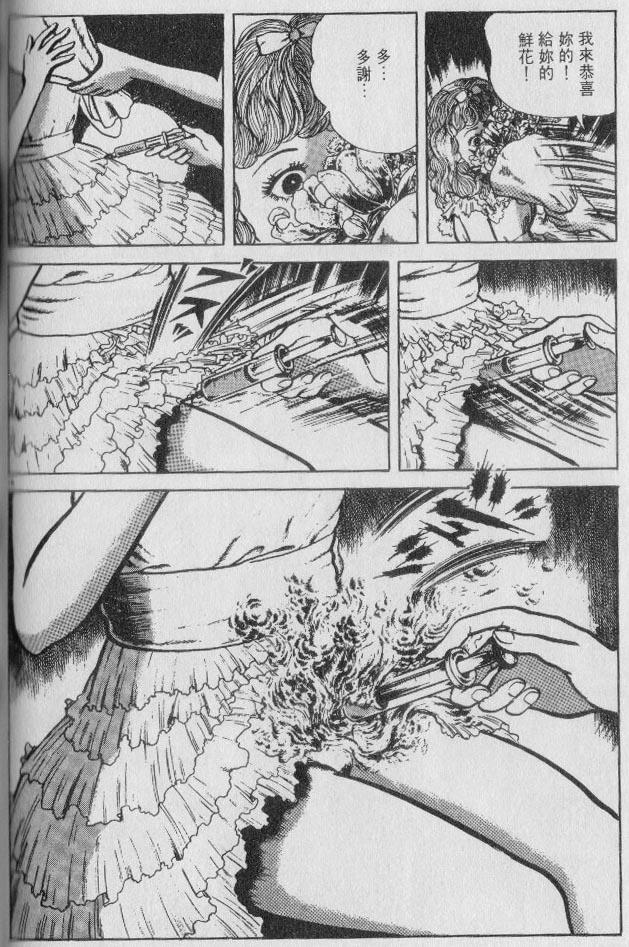

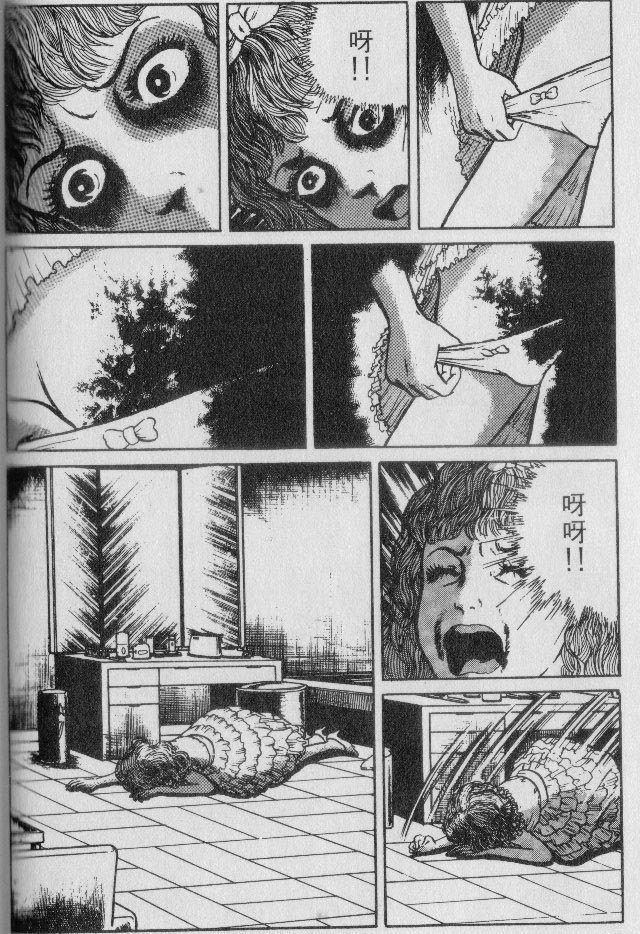

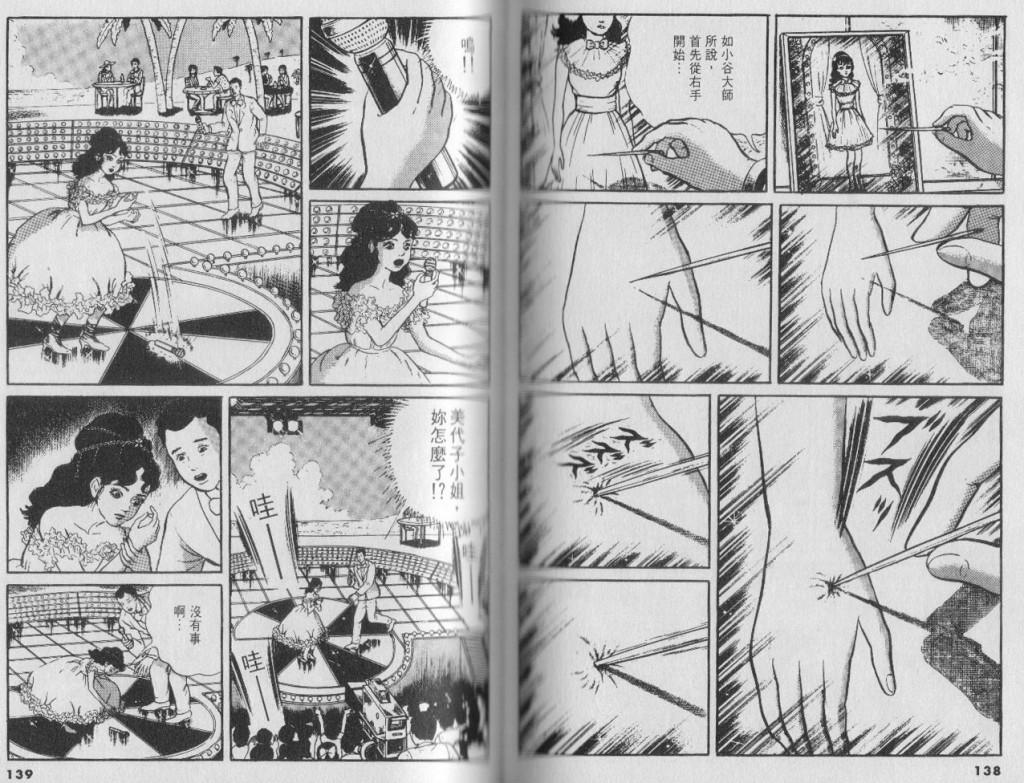

The imagery of Drifting Classroom is itself so primal, and the staging so visceral, that it is often in conflict in a very real way with the very controlled, assistant-heavy surface sheen. Although the textures of Sho’s world are admirably dirty and gritty, all textures that would be put to similar effect by Junko Ito decades later, the surface is so consistent, the characters so on model in all their doe-eyed splendor, that the violence sometimes becomes distanced and almost comical. The effect is similar to that of photographs of dolls torturing each other, or documentation of a war between porcelain figurines. How would the same story read with a surface style as visceral and loaded as the imagery?

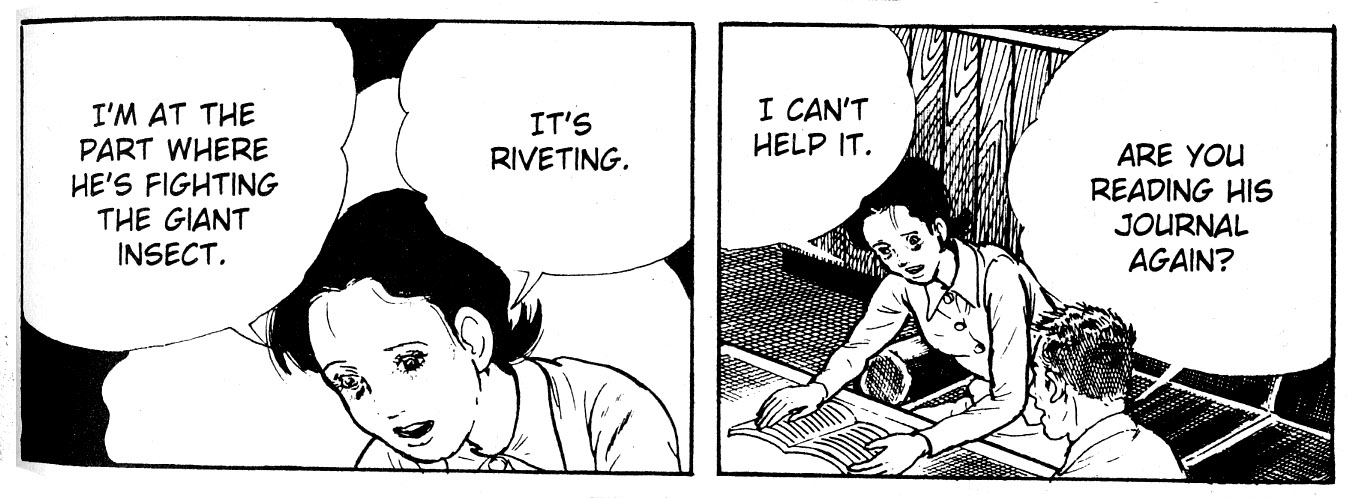

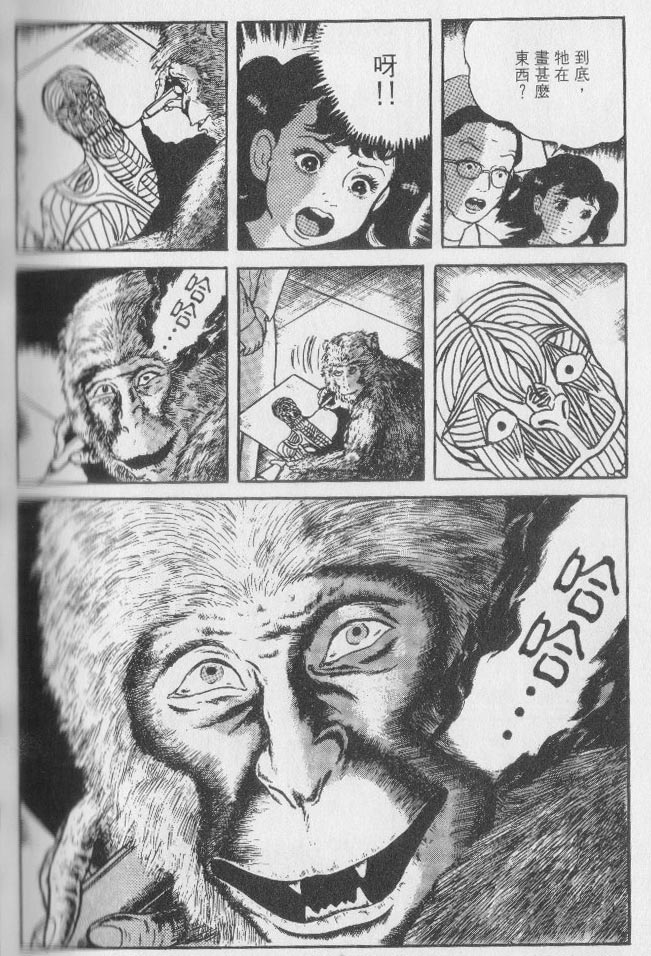

I tell myself it would be better, more attuned to the emotional content, the terror of the events. And then I think more about the later turns of the plot, and look again at one of the hundreds (thousands?) of almost identical drawings of Sho in profile, looking on in horror as another grotesque assaults his friends and his world, and I know that this duplication is part of the effect, that pressed between the pages these doll-like bodies will rip and tear and destroy each other for eternity.

The Process-oriented Apocalypse

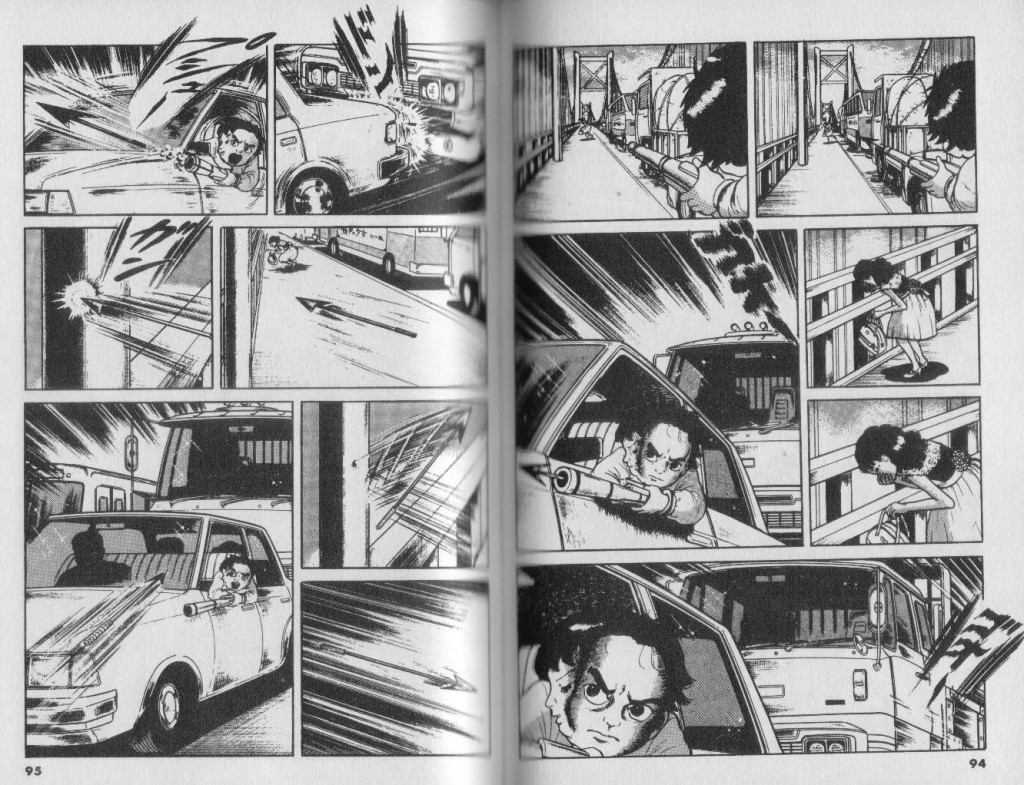

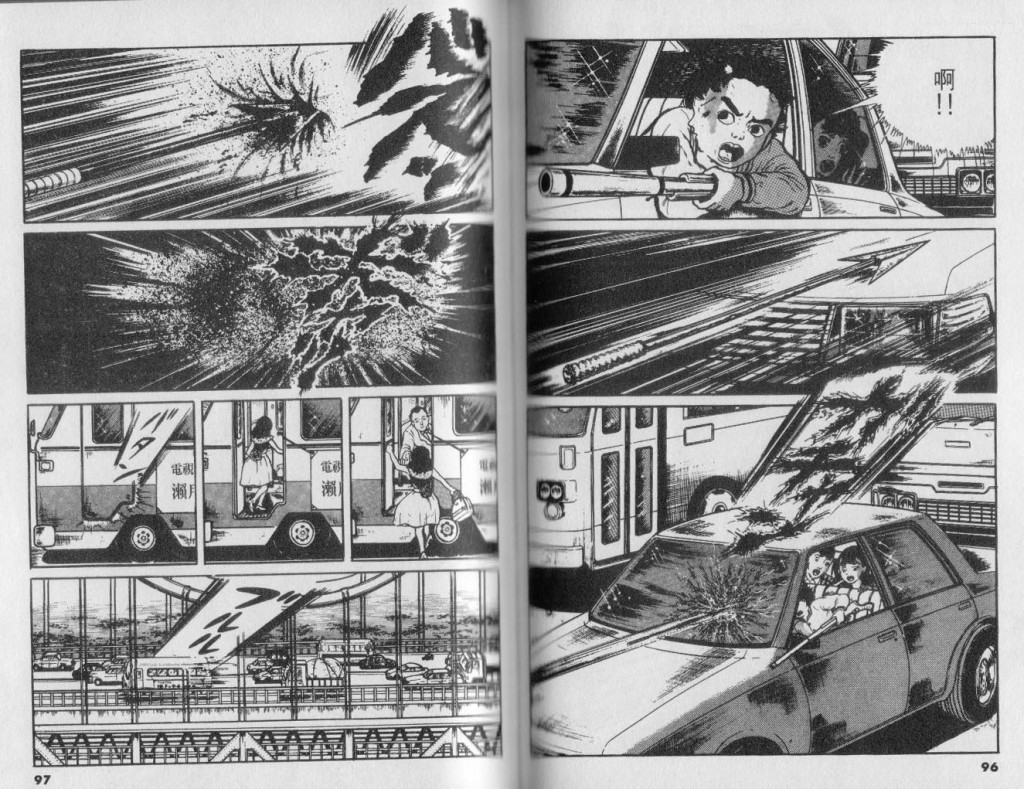

The later stages of Drifting Classroom present a process-oriented apocalypse in which no problem is too horrific or complex to overcome, even if the solution happens to involve psychic time travel, the unbreakable power of mother/son love, or remotely-controlled severed limbs and partial faces that hide out in the backpacks of toddlers. Putting aside the wildly-inventive details to these problems, the solutions, and the need for solutions and explanation in the first place, keeps the Drifting Classroom from ever truly lifting off into the unknown, for better or for worse. Once the proceedings become so focused on process the series becomes almost procedural, not unlike the console adventure role playing games that would infect the youth of Japan a little more than a decade later. Sho leads his party of adventurers through the hostile land, gathering experience points and new skills and objects and information about their world that furthers their chances of surviving each new conflict. Along the way members of their party are picked off by foes they encounter, alternately sentient and environmental.

Although the early portions of Drifting Classroom are truly adrift, the later portions seem to very specifically reflect a worldview of purpose and direction and structure. God, or parent, may be absent from their lives, but He has not forsaken these children—he has gifted them with the intelligence and training to be able to collectively decode the clues around them. Many of them will die, and yes, they have been placed in a truly hellish place, a world devoid of life and growth and promise. But not devoid of hope. The confident, assured, and ultimately perfect Sho shepherds his flock of students through the dangers, knowing that although many of them will pass, their class, their tribe, will live on. Sho is the intermediary between the absent and the present, the bridge between the missing world of comfort and the current world of absence and abscess.

It is not insignificant that he does this while being the protagonist of the story. Although he may represent one Jesus Christ in relation to the children in his charge, he doesn’t resemble him in his role to the text- Jesus, despite being the central character of the gospels, is hardly our viewpoint character. Because we’re intended to identify with Sho, and because he happens to be the target age of the initial publication of the manga, it’s easy to read into Sho a kind of purpose to this entire enterprise that, on its surface, seems like so much mayhem and carnage. Through the blood and the murder and what on the surface seems like a hot, horrible bloody world of randomness, the students, and the readers, are slowly being encouraged to step into that truly adult space of individual agency, of realizing that they alone are responsible for their survival, but that survival is possible, and is in fact within their grasp, guaranteed by the inevitability of invention. There are problems, the Drifting Classroom insists, and where there are problems there must be solutions.

It’s a surprisingly conventional message for a narrative with so many unconventional details, and such uncommon violence.