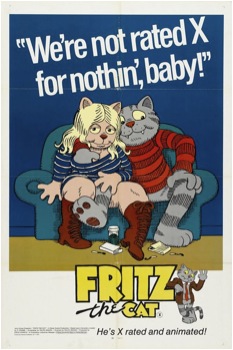

Perhaps against all odds, Ralph Bakshi’s recent success in getting his latest project funded via Kickstarter attests, if not to his current relevancy, then at least to his tenacity. Working in a medium monopolized by Disney and its copycats, Bakshi has been a figure in the American animation scene for decades, producing controversial, if not altogether attractive, animated films that have on occasion gone head to head with the Big Mouse itself. Throughout his career, Bakshi has never tried to make films that are palatable; his breakthrough film, Fritz the Cat, was the first X-rated animated film to get a wide release and was described by no less than Underground Comix grandfather R. Crumb as “repressed”, “fascistic” and “twisted in some kind of weird, unfunny way.” As if trying to live up to such harsh criticism, Bakshi’s films are often raw, angry creations, full of a manic energy that ambles frantically from acerbic subversion to a desultory, formless racism and misogyny that would drive away nearly anyone within the first half hour. Bakshi, especially in his earlier films, works from a paradigm of art popular during the 60s and 70s in the Underground Comix scene which states that anything that makes your mother and government cringe is gold, a philosophy that validates all manner of perversion and political protest as well as any racism, misogyny, or homophobia that happens to creep up on part of the part of the usually white, straight and male artist. Despite, or perhaps because of, the frantic and vitriolic nature of his work, Bakshi remains one of the only artists who has ever locked horns with the animation industry and come out clean; with Fritz and the subsequent film Heavy Traffic, Bakshi became the first animator since Disney to produce two back to back commercially successfully films. But alongside his penchant for controversy and money making ability, Bakshi had, and perhaps still has, something exceedingly rare in the world of American animation; a political drive, an ideology, a statement he wanted to shove in the face of The Man with nothing but his cartoons.

The paradox of Bakshi lies in the disparity between the movement of his work and its actual content; even taking his greatest failings into account, his impact on animation as an artistic medium in the United States cannot be questioned. Taking inspiration from the Underground Comix movement of the time, Bakshi suggested that animation, like any medium of expression, had a social obligation to rearticulate complex social and political issues in new and subversive ways, a line of thought far removed from either mainstream Disney logic or the more mischievous ideology embodied in its counterparts, Warner Bros, Hannah-Barbera, and currently Dreamworks. Speaking to the Los Angeles Times in 1971, a year before Fritz was released, he famously said “The idea of grown men sitting in cubicles drawing butterflies floating over a field of flowers, while American planes are dropping bombs in Vietnam and kids are marching in the streets, is ludicrous.” Alongside this, Bakshi’s animation studio, Bakshi Productions, gave unprecedented opportunities to female and PoC animators at a time when they were virtually nonexistent in the industry. In this respect, Bakshi is unique. Even as animation has matured in the Umited States, developing if not a sense of moral obligation than at least a sly self-awareness, no past or contemporary animator has made a claim as bold nor attempted to follow through on it as Bakshi has.

This drive, towards a redefinition of animation and a shifting of its central paradigms, constitutes the movement of Bakshi’s oeuvre; the content of it, however, falls significantly short. Bakshi once said R. Crumb hated his adaptation of Fritz the Cat because of the added social commentary; Crumb himself said it was because the film was “repressed” and “fascistic”, especially when its climax ended as a condemnation of the radical left. Among the highlights of Fritz are graphic cartoon rape, the depiction of African-Americans as lusty, atavistic crows who only gain a modicum of revolutionary spirit when Fritz wills it into them and an endless parade of women as nags, sex toys and brainless groupies that would make Jack Kerouac uncomfortable. Fritz delights in sex — angry, ubiquitous and in your face sex that feels less revolutionary than it does a big middle finger to mom and dad. That isn’t to say that sexuality shouldn’t have a place at the table, or even that it shouldn’t make the viewer uncomfortable, but watching the endless repetition of cartoon humping carries all the pointed commentary of a Bansky cartoon where the villain is a McDonalds logo wearing a Mickey Mouse hat and carting an M16 Carbine. An idea is present, perhaps, but its execution is so muddled and caught up in its own cleverness it might as well start railing about “the man.” And the main character, Fritz, is a walking, humping manifestation of everything bad on a college campus; a navel-gazing, whiny, misogynistic pseudo-philosopher whose endless drive for “meaning” in a cruel and empty world where he occasionally has to go to classes and gets rejected for sex is supposed to make him a sympathetic character in the viewers’ eyes. Had the movie, perhaps, decided to cast Fritz as a completely unsympathetic character, someone who plainly isn’t fit to run a lemonade stand, let alone a revolution, the tone of the film would be different and its content more palatable. As it stands, however, Fritz remains an almost unwatchable film, and not for the reasons either Bakshi or his right-wing critics would attest.

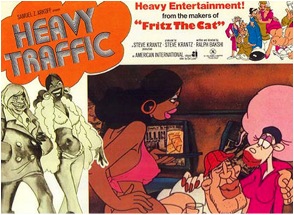

After the tempest that was Fritz the Cat (and box office success, in no small part due to its notoriety) Bakshi’s films seemed turned towards the personal rather than the heavy-handedly political. Heavy Traffic, the film immediately succeeding Fritz the Cat, sought to latch on to the latter’s momentum in what Michael Barrier described in his seminal Hollywood Cartoons as an effort “to push beyond what was done in the old cartoons, even while building on their strengths.” Bakshi, a Palestinian native who grew up in working-class Brooklyn digging through the trash for comics, used the film to channel an aesthetic vision of American urbanity at once instantly recognizable and deeply personal; an America dominated by pinball machines, wafting cigarette smoke, one-word ethnic caricatures and, in the words of the trailer, an amalgamation of “hoods, hustlers, freaks, creeps, cops, crazies, weirdos, rhinos, hardhats, lowlives,” and most interestingly, “god.”

The Brooklyn Heavy Traffic shows us is one of juxtaposed creations; diseased streets filled with tender hearts, crude ethnic caricatures concealing complex interpersonal relationships, slapstick violence masquerading the very real blood shed on the very real streets. It is a crude, violent and raw film, like the best of Bakshi’s oeuvre, and it brims with hazy meditations on the intersections between race, class, gender, and faith in god that defined urban life in this country for generations. What Bakshi lacks in finesse, he makes up for in passion; the film seems at times cobbled together, its live-action, psychedelic, crudely sketched and improvised bits seemingly held together with popsicle sticks and glue. And yet, it holds; the film’s heterogeneous composition only further its vision of animation and of America, both of which position themselves as feel-good, moralistic, and patriotic creations of a master spirit. Bakshi, conversely, seeks out their contradictions, their concealed violence and sex and malice, and creates a pulsing, poetic landscape dominated by the raw beauty of sex and violence, poverty and anger, a contraction of everything America stands for and a declaration of what America truly is.

Following the success of Heavy Traffic, Bakshi’s works over the next two decades divide into three categories; meditations on American life, angry slapstick comedies that are at times, like Fritz, completely unwatchable, and fantasy/sci-fi works that draw as much on pulp-fiction magazines as the traditions of Tolkien. In the span of 10 years, Bakshi had released the quasi-blaxpoitation film Coonskin, the fantasy film Wizards, an adaptation of The Lord of the Rings, and the more Heavy Traffic-esque American Pop and Hey Good Lookin’. Despite being markedly different on the surface, a consistent palette of themes emerge from them; an artistic occupation with bricolage and cut-up techniques, a gritty and purposefully unpleasant aesthetic that often delves into pure surrealism, and the subversion of traditional cartooning techniques to create caricatures of ethnic groups, organized crime, violence and sex, and what it means to have an identity in America. He never, however, fully escaped his prejudices, and the constant stream of misogyny and racism that colors his already hard to watch films is always apparent (Coonskin in particular was a cause célèbre in its time; while Bakshi considered it his masterpiece, its premiere was protested by the Congress of Racial Equality). His fantasy films forcefully attempted to redefine the scope of animation as a narrative device, but often hit walls with recalcitrant producers unwilling to provide funding and had to cut corners; the battle sequences in The Lord of the Rings, achieved through a combination of rotoscoping and tracing animation cels onto live action sequences, look almost embarrassingly amateurish. The animation industry was, and remains, a pathetically timid creature, and even the most successful of directors have had to fight tooth and nail to get any semblance of funding for works not focus-grouped to hell and back. Since Bakshi’s heyday, this has only gotten worse; a proliferation of “self-aware” cartoons, led in part by Bakshi protégé John Kricfalusi’s Ren and Stimpy, fall far short of the in your face fuck you bravura of Bakshi’s works, but manage to slip in a few “adult” references as if to assure themselves they’re not just kid’s cartoons. But the discomfort that Bakshi’s work stirs up is meant to be explicit; it is a calculated political gambit, the kind that the masters of the Underground Comix specialized in. By splattering shocking and perverse imagery throughout their works, Bakshi takes the viewer’s preconceived and carefully crafted notions of cartoons and comics as kid friendly creations and smashes it in their face.

Bakshi’s later films, from upper-left; American Pop, Lord of the Rings, Coonskin, and Wizards

The comic and cartoon, in many ways, has historically functioned as a visual representation of the American political consciousness; it is a sterilized mask behind which imperial machinations thrive, the visual signifier of a moral cosmology that delineates two forces, the strong and just Mickey Mouse/Superman archetype on one hand and the dark, formless evils of communists, fascists, and everyone else on the other. The comics and animation industry, with their blacklists and their codes authorities, were more than happy to play the role of arbiter of American hegemony to children worldwide, and through their influence, a whitewashed, always-smiling artifice of pop culture that took root from Texas to Tokyo. By contesting these novel art forms, the Underground Comix movement hoped to breathe new life into them, to free them from their moralistic restraints and utilize them for methods of individual, political, and sexual expression. But while comics have continued to thrive since the 70s in this aspect, any underground animation movement remains moribund. Bakshi remains perhaps the only exception to the rule; throughout his career, he went head to head with major animation companies and even managed to on occasion break into the mainstream, albeit for reasons he might not have wanted.

But even in the most positive light, Bakshi falls into the traps of so many artists of the time; in attempting to establish a counter-hegemonic force to the mainstream corporate forces they opposed, Underground Comix developed an antagonistic strategy that lamented “political correctness” as much as it did corporate authority, creating a space unwelcoming to anyone who were the victims of systems of oppression those so called “subversive” artists never perceived, i.e., anyone not white, straight and male. Bakshi’s racism and misogyny, no matter how embedded in irony he may have thought they were, are still racism and misogyny at their core, and this remain critical to understanding the shortcomings of Bakshi’s political goals. Also critical to understanding Bakshi’s limitations is examining the direction his work has taken since the 80s; rather than boldly confronting new social and political issues in the aftermath of the Cold War, like globalization, ecological threats to the planet, heightening tensions with the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, or 9/11 and its aftermath, Bakshi seems almost rooted in his own nostalgia, producing little more than the film Cool World, which animation historian Jerry Beck called a “pointless rehash of many of Ralph’s favorite themes,” and a slightly more risqué remake of Mighty Mouse, the cartoon that gave Bakshi his start as an animator in the 60’s.

The mix of race, sexuality and culture in Underground Comix and Animation was rarely a comfortable one.

And what of his most recent film, you may ask, the one mentioned at the beginning of the article? Its title is Last Days of Coney Island, and it promises to have everything you’ve come to know and love from Bakshi; the underside of New York, prostitutes, gangsters, seedy character designs that younger audiences might mistake for Ren and Stimpy characters, and more. There’s something almost tragic to see the man who once produced more bombast (and on occasion, genuine artistry) than any other cartoonist this side of the Pacific working with a set of motifs that haven’t been relevant since the 80s. But such an assessment is enormously unfair to Bakshi; at 74 years old, he’s earned the right to work on personal projects, to conceptualize and illustrate his experiences as an individual rather than as an artistic rabble-rouser. But where Bakshi himself may not have succeeded, the need for a Bakshi-like manifesto remains for animation, for the fact remains that there simply isn’t anyone in contemporary American animation that is doing the type of political bomb throwing he did. That’s not to say that there isn’t excellent work being done by underground artists and animators in the United States, for their certainly is, but little of it has had the scope and reach of movies like Fritz and Heavy Traffic in their heyday. This can partially be attributed to changes in the animation industry in the whole as well as to changes in the political composition of underground artists that have made it refreshingly more queer, PoC and female-friendly, but any attempt at synthesizing the techniques, outlooks and technologies developed since the ‘70s has been minimal.

Ultimately, I would predict many of Bakshi’s films as individual works will be forgotten. Their racism, their misogyny, their formless anger and hatred makes them politically “incorrect” but more importantly politically conservative, reactionary and morally reprehensible. Aesthetically, they have not aged well with time, and their ultimate artistic value for many may simply be as relics of a long-forgotten counterculture movement and its sensibilities. But the need for a political Bakshism, and for the opportunities Bakshi’s animation studio created, will remain. In the years since Bakshi’s semi-retirement, animation has become increasingly complacent, animators increasingly maligned and mistreated by their production companies, and with the exception of more amateur creations produced through online collaboration, the medium itself has been increasingly displaced by more technologically advanced live-action works. In order to develop critically as a medium and retain clout in the way comics, and increasingly video games, have, animation needs more Bakshism, more rabble-rousing and anger and impetuses to collaborate, to subvert, and to pursue “adult” themes and narratives without needing to dress them up in kid-friendly formats. What it does not need is Bakshi’s racism, sexism or the general immaturity that colored so much of the Underground Comix movement of the time. Even if we forget Bakshi, we cannot, and should not, forget the movement that he struggled for, a movement both towards subverting American culture and media and redefining the parameters, depth, and meaning of animation itself.