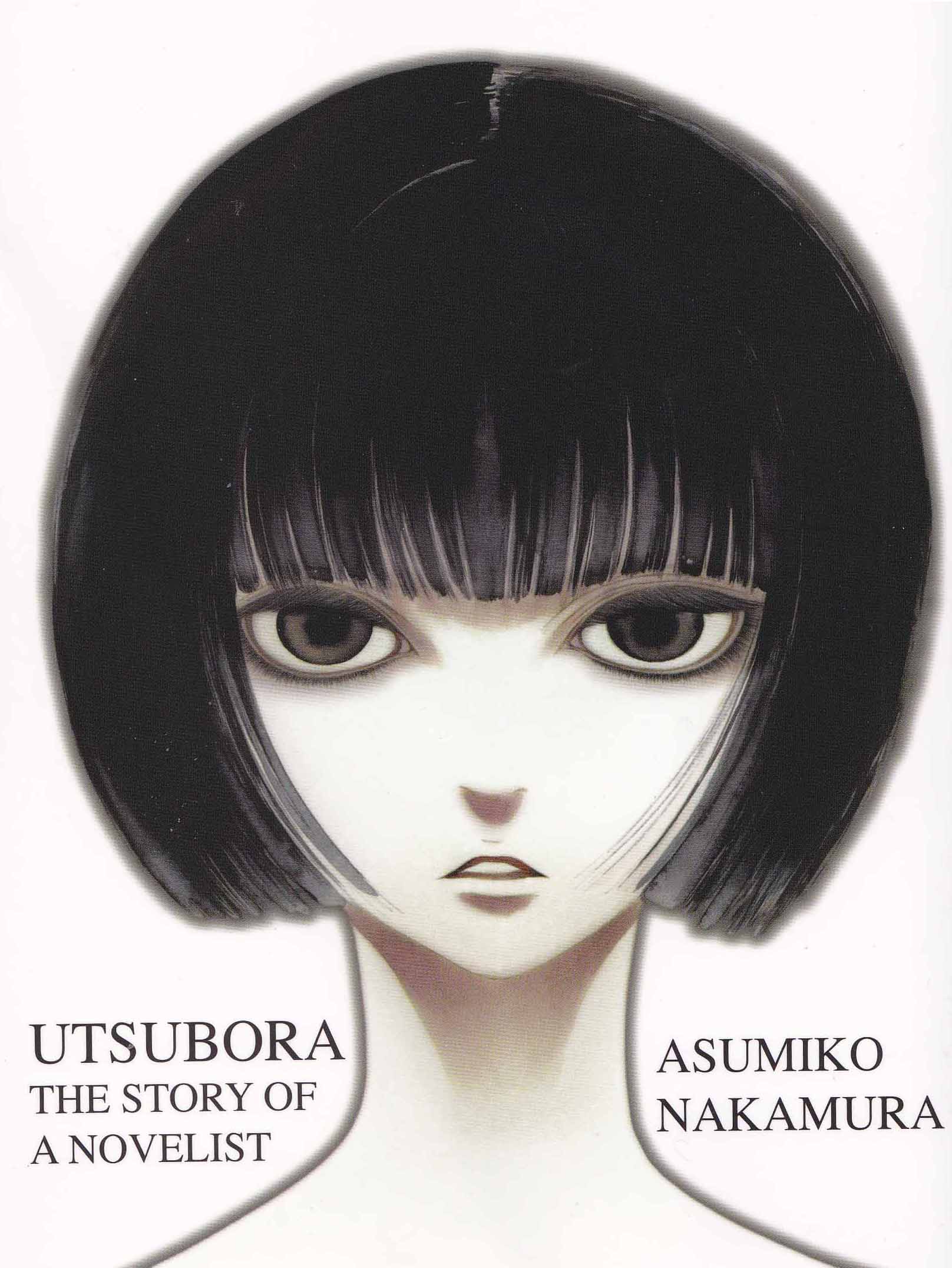

“Utsu…means “depression” or “melancholy.” Tsubo…mean “urn.” …in addition to connotations of a hinter emptiness, the title strongly echoes nouns with a contrary impression of crude vitality… Utsubora is baffling yet familiar; negative yet animate; empty yet organic.” — the editor, Utsubora.

The word online is that Asumiko Nakamura’s Utsubora has had dismal pre-orders. First published in 2008-9 in the pages of Manga Erotics F, it has been released to a patter of enthusiastic notices (see reviews listed below) but little else. While eroticism might sound like a sure seller, this is less the case when it is sold under the guise of “literary” seriousness (the English language edition is by Vertical which does a lot of well-designed Tezuka). And there is certainly a vague kind of high-mindedness trying to crawl out of Nakamura’s manga which is ambiguously subtitled “The Story of a Novelist.”

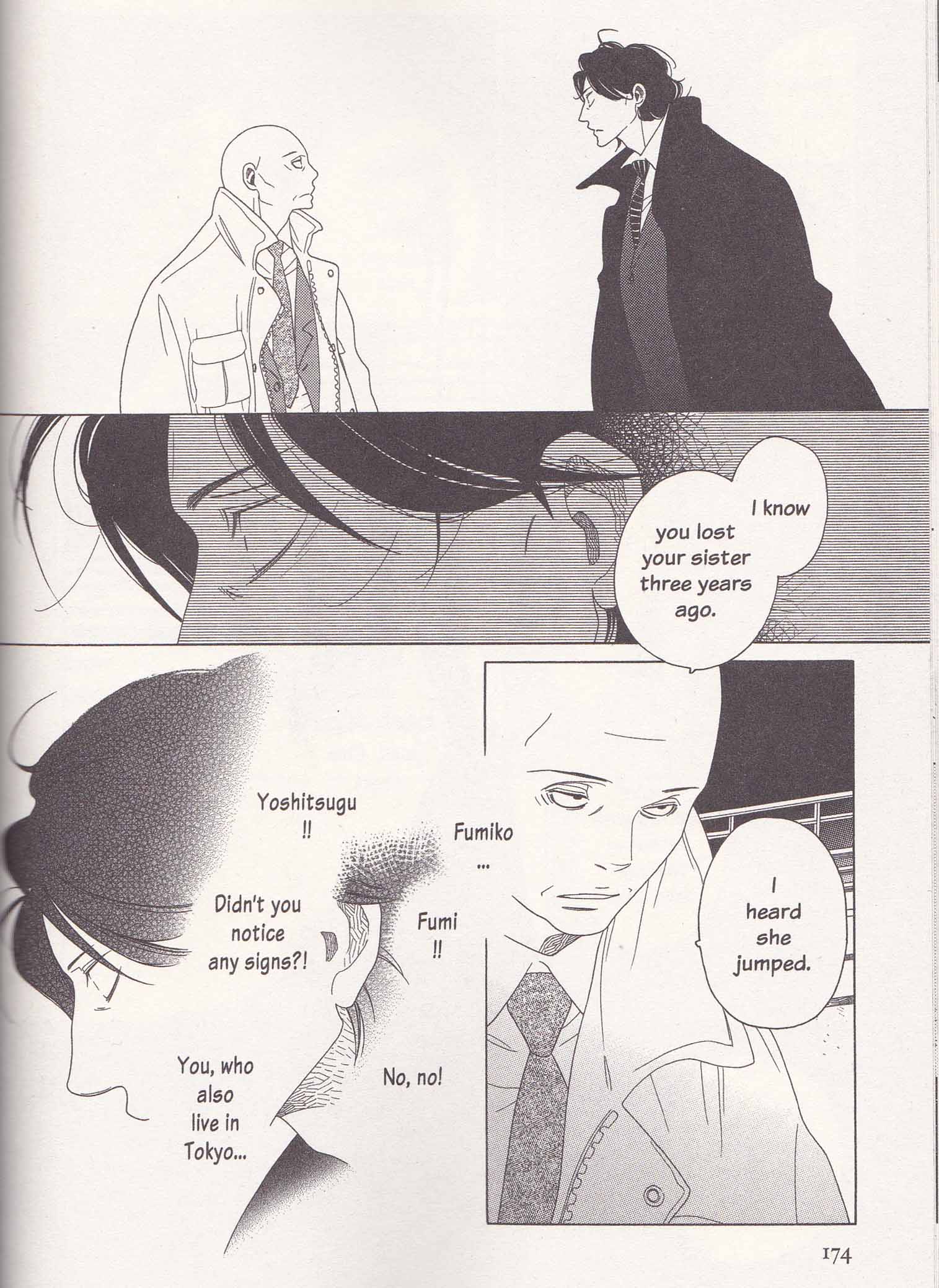

In the opening pages, a pallid statuesque beauty jumps head first from a tall building leaving an unrecognizable mess on the pavement below. A famous novelist, Shun Mizorogi, is called in by the investigators to identify the body (thought to be that of Aki Fujino) a clearly impossible task since only her lower limbs are well preserved. As it happens, he is one of only two names on her phone contact list and hence a suspect. At the morgue, he meets the victim’s twin sister, a sphinx-like creature going by the name of Sakura Miki, a cipher who leaves a list of false contacts for the police but somehow clings to him in a symbiotic or perhaps parasitical relationship. He has been plagiarizing her sister’s (a budding authoress) manuscripts and becomes dependent on Miki for the remainder of his serialized novel which is also titled, Utsubora. The rest is a metaphorical ramble around questions of authorship and creation, played out in the mystery surrounding the lives of Aki and Miki.

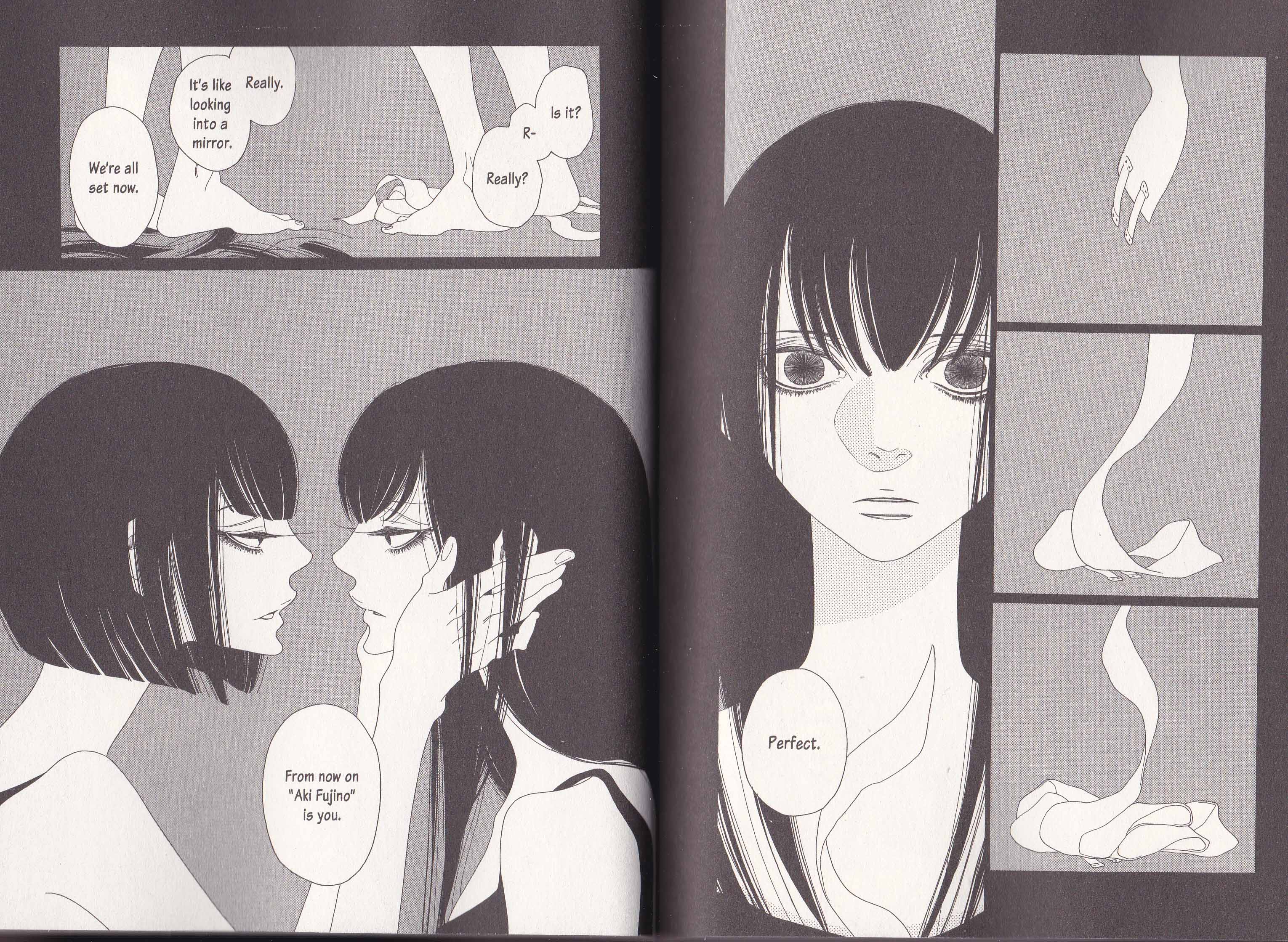

One could be forgiven for assuming that the novelist of the subtitle (an editorial addition or in the original?) is the male protagonist whose fate structures the story, but Nakamura’s ambiguity is purposeful—that appellation refers not only to Mizorogi (the male author) but also the plagiarized suicidal authoress (Aki Fujino), and Nakamura herself. Aki and Miki are not so much characters but personifications of author and story. The “true” author of Utsubora is the woman (Aki) seen flinging herself head first to the sidewalk, a shadowy figure who is seemingly plain and unadorned but then transformed by means of surgery to the physical likeness of her friend and self-professed sister, Miki (the female protagonist of the tale).

This plastic surgery has less to do with soap opera conceits than the way an authoress’ appearance and personality is transformed ( in the imagination of her readers; and personally and insidiously) into something else—a physical likeness of similar, angelic temperament; mysteriously distant yet welcomingly sexual; a hidden, mythic, and unaging figure. A vision of how personal experience when turned to fiction can lead to the molding of the writer herself. We can detect a plot of similar temperament in Roman Polanski’s The Tenant where the actor-director becomes the object and victim of his fears in a movie of his own conception. In the structure and premonitions of Utsubora, we can see an echo of the fatalism of Nicolas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now—Donald Sutherland’s almost authorial paranoia in that film being the impetus of the plot and entire movie. It is this mixture of grief, writerly fixation, and eroticism which creates that tinge of horror in Nakamura’s manga.

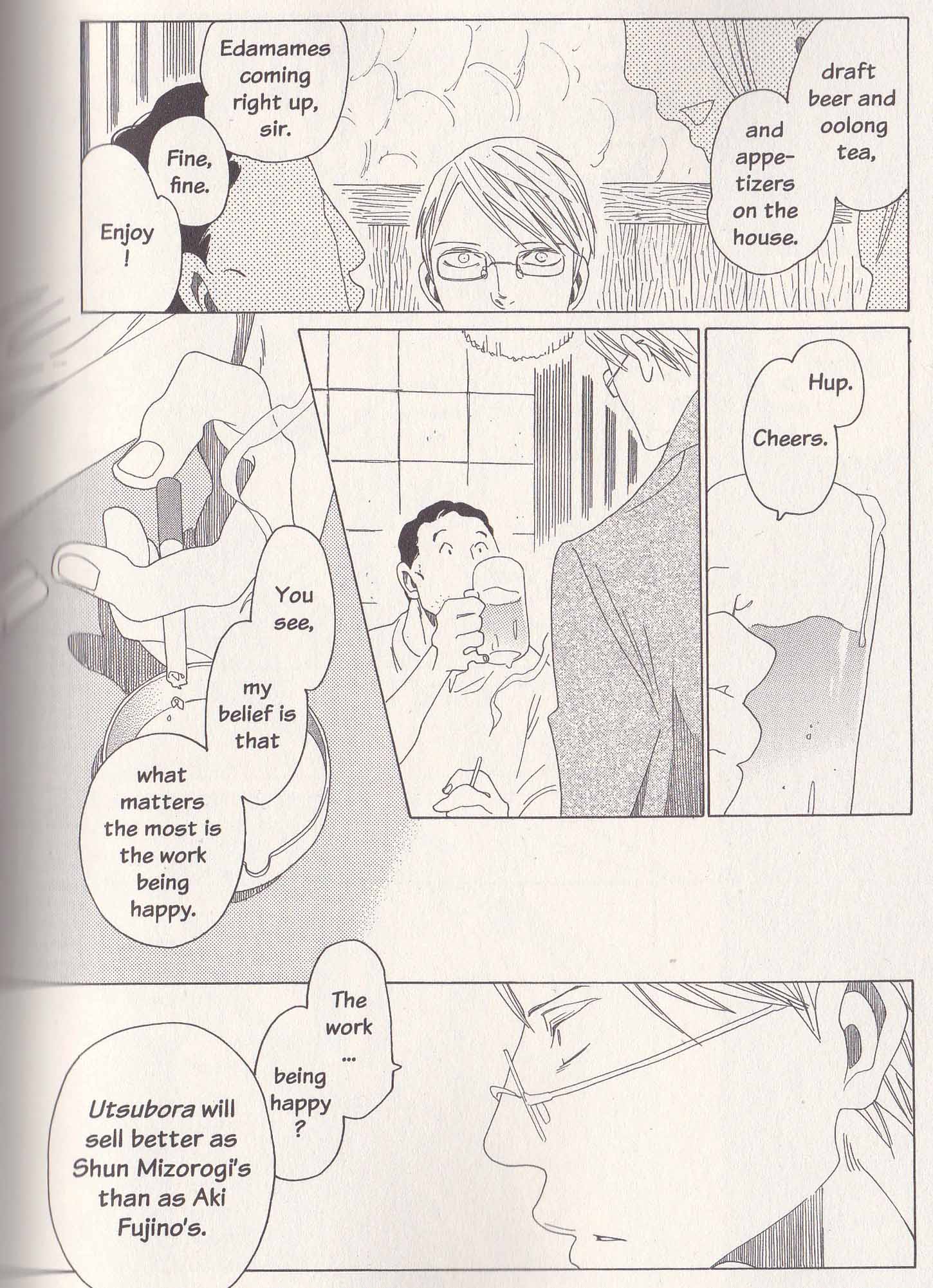

Miki is the personification of Aki’s (and Nakamura’s) story. In deference to this, she is frequently seen conveying handwritten manuscripts to either Shun Mizorogi or his editor. At other times she is depicted against scattered sheets of drafts. The moment Utsubora is released in its final form by Mizorogi is also the moment she disappears from the manga as a character—turning at once into a caricature of the typical cheerful manga heroine—her job and reason for existing finally brought to a close. That segment of the manga where Mizorogi’s editor debates the primacy of the story over authorial credit seems a moment of metatextual self-realization, one might even say a kind of sentience on the part of the manga. It is easy to see a trace of personal experience in that conflict between the physical availability of a story and the act of plagiarism.

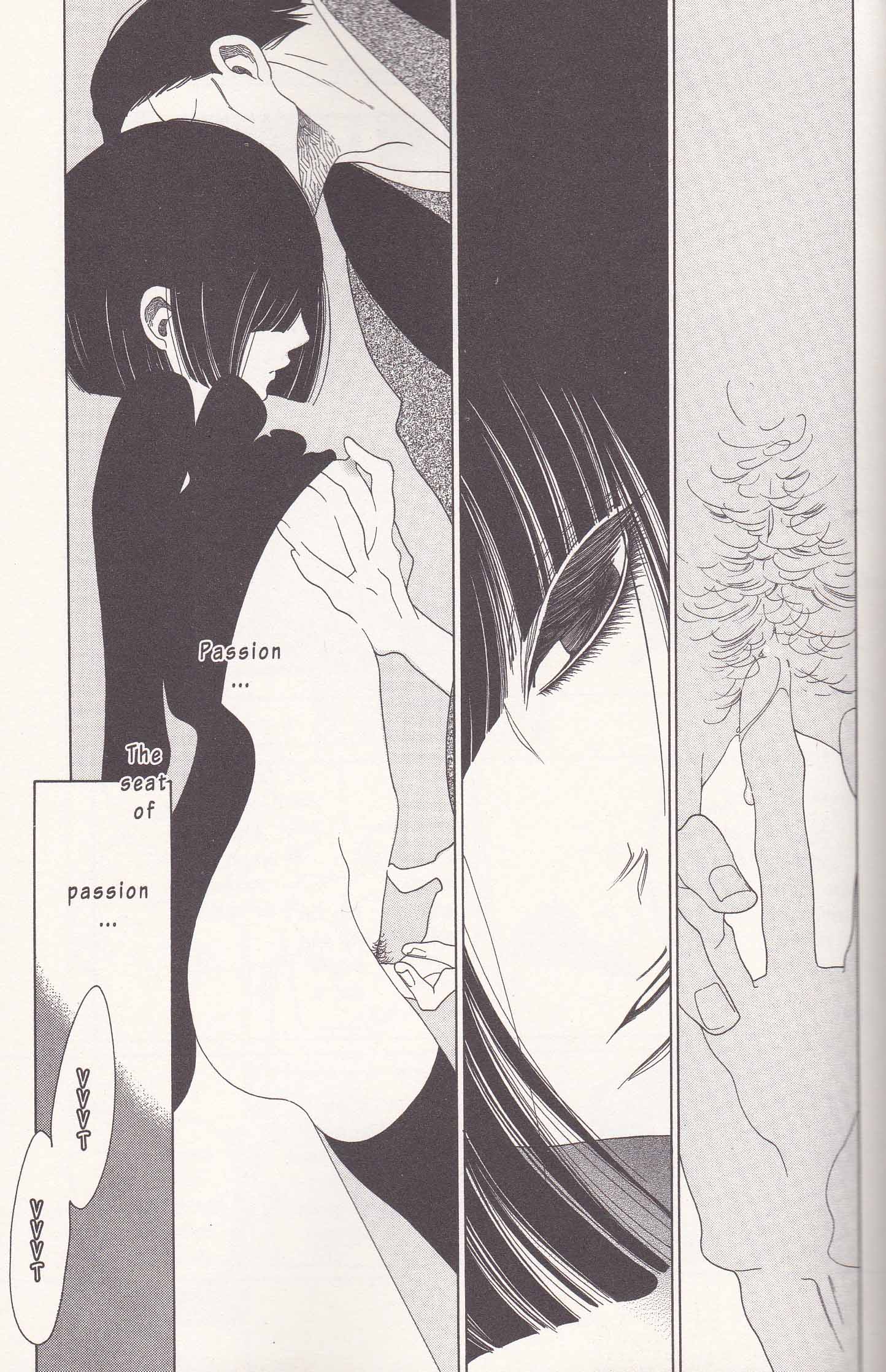

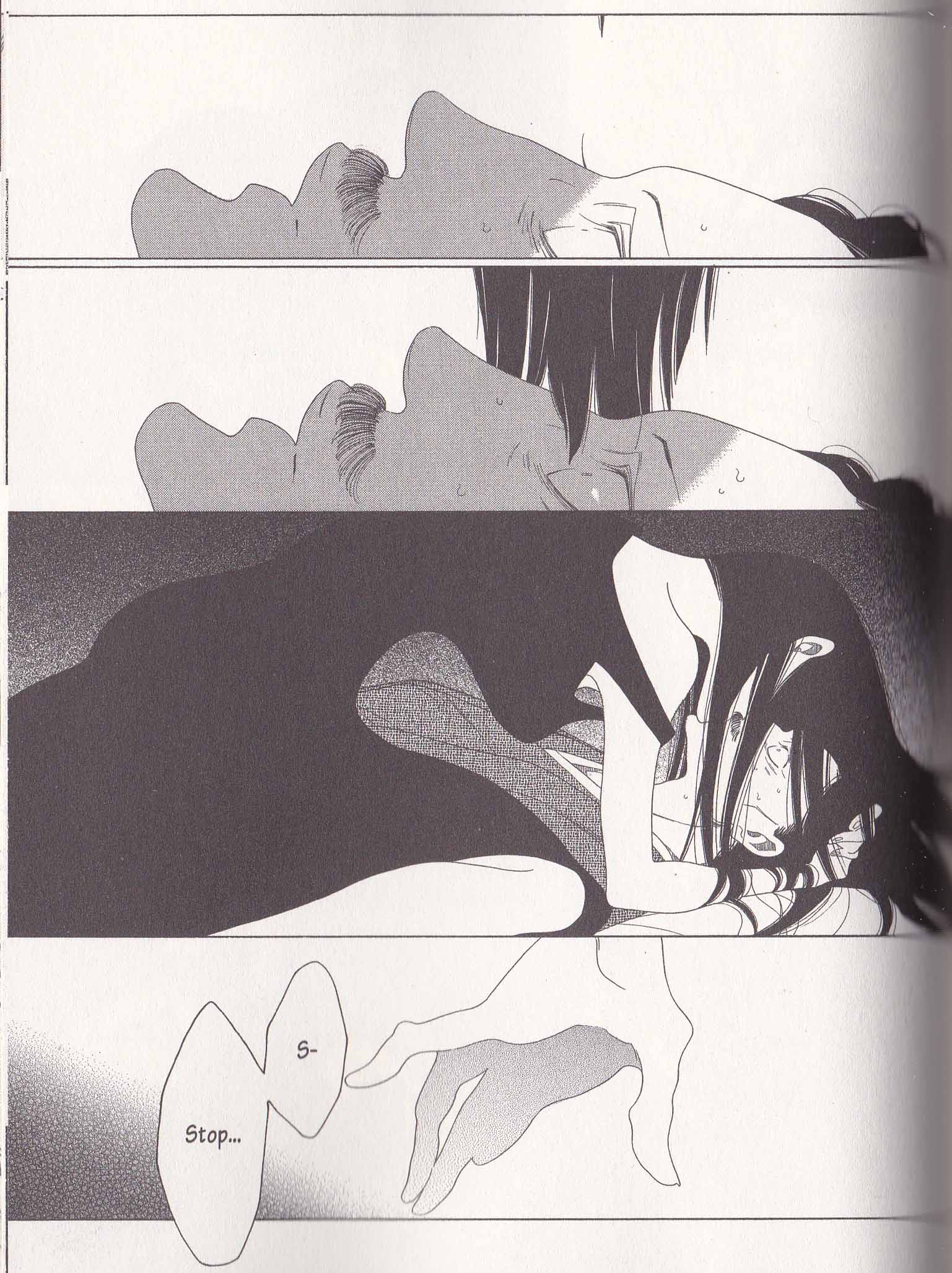

As for the eroticism, the authoress seems to take a singular delight in finger fucks but appears more abashed by actual coitus. Scenes involving the latter are broken up and defused through her panel work and other forms of obfuscation. The blow jobs depicted are undeniably squalid and damp; it is an act which is depicted with contempt and disgust.

One might see in this a decidedly feminine approach, the use of lengthy fingers being more readily available or even more attractive than the male sex organ (I have yet to read any of Nakamura’s Boy’s Love manga to confirm this). The reiteration of this device in comics will undoubtedly suggest the work of Guido Crepax to a Western audience—that arch student and adapter of all forms of literary smut. That penchant for gnarled, stringy hands inserted into orifices, as well as a boundless attraction to the sopping juices of a tight cunt are all hallmarks of that Italian cartoonist.

Nakamura’s delicate minimalism and elongated figures suggest the work of Aubrey Beardsley and the smattering of reviews I’ve read offer up an amalgamation of this Western eroticism and that found in Ukiyo-e in explanation of the final product (though examples from the latter seem considerably more frank).

Crepax’s vision suggests violence and control while Nakamura’s allows for desirability and fulfillment; an almost feminine coyness about the penis which is quite the reverse in Crepax where the male organ is an erect weapon.

Despite all this, there are immense difficulties for the would be reader before we get to that final moment of legerdemain. There are about 50 pages of scattered plot here fluffed out to 450 pages of mind numbing repetition of figuration and expression, as well as pointless nudity and pin-ups. All to often this is a suspense novel without any suspense, an exercise in eroticism without sensuality, a depiction of authorial obsession with nary any artistry—a torrent of metaphors with almost no consequence or real depth. It’s as if you bought a comic and all you got was paper and ink. The high page count and, one suspects, the pace of publishing has resulted in far too many pages of quite insipid mood, depiction of place, and composition. Only at the end does some form of concentrated artistry rear its head.

The flurry of barely developed plot devices is oppressive and infuriating. For instance, the incessant cradle snatching and the reassertion of the “natural” attraction of young girls for boring wrinkly, old farts (especially when they spend all day cooking for them)—all this clipped from the celebrated annals of incest in Japanese Adult Videos. Yes, even female mangakas can be idiots (or maybe ironic, it’s hard to tell). Tired tropes abound, it is almost as if dutiful eroticism had anesthetized creativity. And thus we have Aki as an assertive succubus, entrapping the author with her wiles and literature, her form transformed not by smothering the devil’s bottom with adulation but by heeding the surgeon’s knife.

The tear jerking moment when Nakamura lifts a plot point from episode Z of your favorite police procedural crap—the cop who gets overly involved because the victim reminds him of his sister (or was that wife, mother, or child)—is certainly incitement to book burning.

A trying experience then but one alleviated by a lengthy and well inscribed denouement—the solitary reason one might pause in the act of casting a copy into the outer darkness to mention this work at all.

_____

Other reactions

There aren’t many to choose from as yet but there’s a review by Sean Gaffney, another at Otaku Champloo, and finally one by Connie C..