The titular protagonist, posing as the Bogeyman

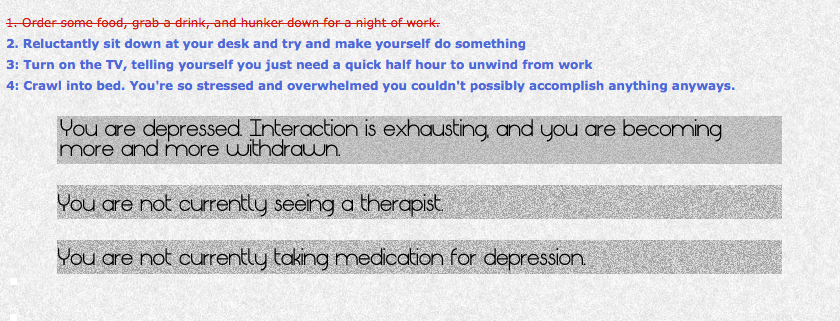

The Sly Cooper series is one of the most beloved games of the PS2 era, one of the so-called “Holy Trinity” of PS2 platformers. The series features a world full of anthropomorphized animals, where Sly Cooper, a roguish raccoon, and his friends have a series of globetrotting adventures pulling off heists in all sorts of exotic locales. The series is lovable, charming, and exciting, and the news that it’s getting a CGI movie release for 2016 has me overjoyed.

Oh, and it really, REALLY hates poor people.

Maybe I should start from the beginning…

Intro: The Basics

The narrative of the game revolves around Sly Cooper and his allies fending off threats to his family legacy. It positions the protagonist as a rightfully privileged hero, and the antagonists as nefarious class usurpers. At every turn, the series reinforces the idea that the Bad Guys are bad guys because they challenge social hierarchy, directly or otherwise, and that the Good Guys are good guys because they are defending Sly’s bloodline, which is presented as inherently good for arbitrary and never-questioned reasons.

Sly 1: F@$! The Haters

The whole series starts with you learning about Sly’s central motivating tragedy. He’s descended from a long line of master thieves that aggregated all of their thieving knowledge into a single book that has been passed down through the generations. This clan takes pride in only stealing from other thieves, as they consider it the ultimate test of skill to rip off another larcenist. The very night Sly’s father was going to give him the book, five mysterious strangers invaded and ransacked their home. These strangers, known as the Fiendish Five, murder Sly’s father and tear the book into several pieces, retreating to the far reaches of the earth with their respective parts. This brutal and bizarre crime lands little Sly in an orphanage with nothing but his father’s cane, where he meets Bentley (a turtle, and the brains of their gang) and Murray (a hippo, and the brawn of their outfit). They quickly become fast friends and start stealing stuff, honing their skills for the inevitable day when they would embark to recover Sly’s inheritance.

Why do Bentley and Murray agree to dedicate their lives to Sly’s inherently selfish revenge scheme? How did they end up in the orphanage and what are their backstories? Who knows? The answers to these questions are never provided. In fact, Sly is the only character in the whole series with a self-contained backstory. Bentley and Murray (and every other character you meet) seem to exist for the sole purpose of aiding, validating, and/or antagonizing Sly throughout his journey.

The first antagonist and member of the Fiendish Five, Raleigh, seems to contradict the thesis proposed above. He is the aristocratic British heir of a sizable fortune, turning to modern piracy out of boredom. Frankly, he’s a pretty straightforward jerk.

Not so with the second, Muggshott (a bulldog), or the third, Miz Ruby (an alligator). Both are bullied and ostracized as children. Muggshott pursues control of his social circumstances through bodybuilding, and Miz Ruby pursues control over her environment through her magical voodoo powers. Both turn to crime because…the story needs Bad Guys. There is never any clear motivation given for their choice to enter high-stakes crime. Instead, you are left to believe that in the process of overcoming their marginalization, they simply became evil.

Fear the victims of bullying. Feeeeeaaar theeeeeeeem.

The story of the fourth member, the Panda King, is even more absurd. He was born and raised poor in China. In order to escape poverty and indulge his love of the art of fireworks, he put together a display for some noblemen, who ridiculed him for his poverty. In response, he swears revenge on his critics and uses fireworks to pursue crime. But not only is this runaway poor person thin-skinned and uppity, he’s also a sociopath. In the first level of his portion of the game, you see him bury a village under an avalanche. No reason for this action is ever given (except for some vague line about extortion), and you only see this incident from afar. In fact, you never see any bystanders harmed by Sly’s enemies, although you are frequently told he is helping innocents. You never see their faces, and Sly keeps everything he steals. He’s not Robin Hood. Instead, you are led to believe that a process of competitive larceny, whereby Sly ruins somebody and Inspector Fox rushes in to mop up, is a virtuous, populist societal good, without ever seeing the populations being “saved.”

The Panda King calls Sly on this when they finally meet, rumbling, “You are a thief, just like me.” Sly scoffs back, “No, that’s only half right. I am a thief…from a long line of master thieves. Whereas you…you’re just a frustrated firework artist turned homicidal pyromaniac!” Not only does Sly specifically cite his bloodline and inheritance as evidence of his moral superiority over the King, he explicitly links his enemy’s failed attempts as an artist, and by extension, his failed attempt to exercise upward mobility, to his violent, evil tendencies.

The Big Bad of the game, Clockwerk (an owl), further validates Sly’s bloodline through contrast. Clockwerk shows up in virtually every image of a Cooper clan member that you see, but only as a shadowy silhouette in the background. He is an ancient nemesis of the Cooper clan, so envious of the Coopers’ thieving abilities that he mechanized his body to live until the day he destroys the Cooper line. His stated goal is to end the Cooper lineage, steal their relics, and make their name fade into obscurity, and his stated motivation is envy. That’s it. No other plans. He just hates the Cooper bloodline and inheritance so much that he founded the Fiendish Five solely to kill them all. Here, you, the viewer, are asked to accept some dizzying circular logic: the Cooper legacy is worth protecting because Clockwerk hates it and is evil. But why does he hate the Cooper legacy? Because the Cooper legacy is good and he is evil. He is so evil, in fact, that the whole second game is largely about stealing and destroying his mechanized corpse…

Sly 2: Return of the Haters

After the events of the first game, you learn that Clockwerk’s mechanized body parts are in a museum, oddly enough. Sly and his Super Friends attempt to steal the parts, because they believe that Clockwerk could be revived and threaten the Cooper line once again. Unfortunately, a new set of villains in the form of the Klaww Gang, have stolen the parts first, for nebulous and nefarious purposes. In order to protect the Cooper line from future threats from Clockwerk, Cooper and Co must steal them back.

The game wastes no time explaining how evil the new guys are. The first couple of criminals you go after follow now-familiar templates. Dimitri (a…newt, I guess?) is a failed artist who turned to forgery and racketeering after being laughed at by the art world, and Rajan (a tiger) escaped poverty in New Delhi by using drug trafficking to build up enormous wealth. In both cases, you see these formerly marginalized individuals showing off ostentatious wealth in the form of Dimitri’s nightclub and Rajan’s “ancestral palace.” In both cases, that wealth is accumulated through work, not inheritance. In both cases, the game constantly ridicules these men for being so egotistical as to show off their earned wealth, as well as demonizing them for threatening Sly’s bloodline without knowing.

Here we witness the repulsive spectacle of a poor person making money.

It is worth noting that in the process of taking down Dimitri and Rajan, the Cooper Gang are aided by a mysterious colleague of Inspector Fox named Constable Neyla (a panther). At the moment they nail Rajan, the Cooper Gang are betrayed by Neyla, who imprisons them. From this moment on, Neyla is a recurring enemy, whereas before, she served largely as a plot spur providing periodic missions. This role is taken over by Inspector Fox, who Sly refers to as the biggest reason “this is all fun.” Law enforcement serves as a game mechanic, contributing to the global adventurism of the protagonists. The moment the law enforcement become characters with personal motivations outside of Sly’s adventures, they become evil.

To illustrate the point, Sly and Murray are thrown in a prison operated by the Contessa (a black widow spider), a warden affiliated with Interpol. Bentley seeks to rescue his friends, and learns in the process that the Contessa is an expert in hypnotherapy, which she uses to rehabilitate her inmates. But (gasp) there is a nefarious catch. Her hypnotherapy erases her inmates’ criminal tendencies, allowing them to reintegrate into society, but she also uses hypnosis to force inmates to tell her where they have stashed their criminal fortunes. Upon learning this, Bentley gasps, “That dishonors thieving and law enforcement at the same time!!”

To restate that differently, the Contessa steals the fortunes of other criminals…which is exactly what the Cooper Gang does. It’s the whole point of the series. It is extremely hard to discern what nuance makes the Contessa’s way of doing it so much worse than Cooper’s. If it’s the hypnosis, the Cooper gang have drugged, beaten, blown up, and otherwise brutalized their opponents on a regular basis. If it’s that she utilizes the aid of law enforcement, the Cooper Gang used Neyla’s help to take down two prior marks. If it’s that she is evading detection, Bentley is actively trying to break his friends out of prison. And yet, the narrative supports Bentley’s gasping assertion, despite its utter hypocrisy and self-righteousness.

Perhaps it has to do with the Contessa’s background. The Contessa is a black widow, both literally and figuratively. he came into her own astounding fortune, including her ostentatious Gothic castle, by marrying a wealthy Czech nobleman and then poisoning him. The explicit reason for her evilness is her murder and deception, but the narrative precedent suggests it’s her inheritance by marriage that is more offensive, as opposed to Sly’s virtuous inheritance by birthright.

After steamrolling the Contessa, the Gang target Jean Bison, a Gold Rush-era prospector who was frozen in ice for roughly 150 years before thawing out and building a freight-and-timber empire in Canada (it’s a weird game). Jean Bison aspires to “taming the Wild North, damming every river, and chopping down every tree, with progress delivered at the sharp end of an axe.” Jean Bison’s criminal enterprises exist to “bankroll his one-man war against Nature.” The Cooper Gang steps in, not just to steal from Bison, but to, “save the environment from his twisted sense of progress.” In other words, it’s not corporate entities, or societal consumption habits that are to blame for environmental destruction. It’s the backwards, anachronistic, white working class, and that bloc is so powerful and intimidating that only a royal heir like Sly Cooper is capable of stopping them.

All Hail the unstoppable lumberjack overlord!!

The equation of marginalization to evil becomes most blatant with the boss of the Klaww, Arpeggio (a parrot). Arpeggio is a bird whose species should be able to fly, but his wings are stunted, and therefore, useless for flight; he’s effectively disabled, but the game has absolutely no sympathy. He pursues an education in engineering, taking inspiration from Leonardo Da Vinci in a quest to create prosthetic enhancements, which the game presents as a megalomaniacal pursuit that ultimately leads to his criminality. He also takes on Neyla as a protégé, who has been working with him under Interpol’s nose the whole time in an effort to reassemble Clockwerk’s body as an exoskeleton. Sly confronts them, Arpeggio rants, Neyla betrays them all and fuses with Clockwerk to become immortal, and the Gang has to stop her, or some such nonsense like that.

But if Neyla is a cop, an inherent authority figure and a powerful person in this world, isn’t the game saying that privilege and power are dangerous and corrupting? In answer, the game’s manual gives us Neyla’s backstory. She grew up poor in New Delhi and scammed her way into, and through, a prestigious British university. Interpol caught her, but was so impressed by her scam that they gave her a job (so she could “get into the criminal mind”). So the answer is that privilege and power do corrupt…if you weren’t born into them in the first place.

This monstrosity is what happens when you let poor people get an education.

After a big battle, the Cooper Gang takes down Clock-la, who now hates the Cooper lineage, despite a complete lack of narrative precedent. In the money-shot of the whole game, the Gang extract Clock-la’s “hate chip,” the source of Clockwerk’s immortality and power, and crush it underfoot, causing all the Clockwerk parts to rot. The triumphant finale of the whole game is Sly’s destruction of evil, which is almost exclusively a threat to his bloodline. Why should you want to save this bloodline? Because it’s the Good Guy’s bloodline and hating it is evil. Kumba-friggin’-ya.

Sly 3: In Defense of the Natural Hoarder of Things

It is a testament to human creativity that after all of the political mess in the first two games, the third game remixes the old garbage into something fresh. This time around, the Gang is on a mission to open the fabled Cooper Vault, a giant safe in the side of a mountain on an island in the South Pacific that stores the stolen riches accumulated by the Cooper Clan throughout history. The only obstacle is that the island in question is already inhabited by a madman, named Dr. M, who has built a well-staffed fortress in order to crack the impervious Cooper Vault. The Vault’s key is Sly’s cane, but the Cooper Gang need to go recruiting to assemble the talent necessary to infiltrate the fortress and get anywhere near the Vault. More globetrotting ensues.

The first two enemies Sly faces walk the trail blazed by Jean Bison in Sly 2, namely, that of the evil white working class.The first thug, Octavio, is an Italian opera singer who was rendered obsolete by the onset of rock ’n roll. He and all of his diehard Italian fans form a mafia that sets out on a dastardly plan to sink Venice into its own canals in a bid to get attention (seriously). In order to destabilize the Venetian foundations, Octavio pumps tar out from under the buildings and into the canals, which enrages Sly, Bentley, and Murray, as an example of environmental degradation. This absurd scenario uses vapid, misplaced environmentalism to laugh at a white working class losing cultural relevance and clout, setting up Octavio and his goons as a punch line, rather than real characters.

But if the game sneers at Octavio, it snarls at the Australian miners Sly goes up against next. Out in the Australian Outback, Sly and his friends decide that to recruit a local mystic, they must first help him drive off the miners ravaging the environment in search of precious gems. There are no corporate logos or managers anywhere, just a mass of wayward workers, and the game reserves particular viciousness for these nameless average Joes. In order to drive off the miners, the Gang incinerates them on electric fences, unleashes pickup truck-sized scorpions into their mineshafts to slaughter them, and feeds several of the miners to a local crocodile in an effort to get the croc to “develop a taste for miner.”

That miner is about to be fed to a crocodile…and he’s the bad guy.

All of this arbitrary retribution is exacted against the nameless working masses in the name of “the environment,” without ever showing the populations affected adversely by the miners. At the end of Sly’s conflict with the miners, a cut-scene shows the “rescued” Outback, an expansive open desert with little vegetation and no wildlife, for which you have slaughtered hundreds. But the game still presents this pointless violence as inherently good, for seemingly no other reason than that the protagonist “saved” something from the unwashed laborers.

But at this point, the game tires of pissing on labor, and instead pontificates on how terrible royal heirs who aren’t Sly can be. To illustrate, the narrative travels to China, where the Gang try to recruit the Panda King as a demolitions expert by agreeing to rescue his daughter from the ruthless General Tsao (a rooster). Tsao is the heir of a long royal line, and he kidnaps the Panda King’s daughter, Jing King, in order to marry her and augment his family line. Until the wedding, he imprisons Jing King and basks in his own image like a peacock. Like Rajan before him, he has the gall to show off his wealth in the form of an opulent mountain fortress/palace/monastery. But the way the game signals to you that he’s a Really Bad Dude is his insistence that his bloodline is better than Cooper’s. For some utterly unknown reason, Tsao is as obsessed with denigrating Sly as he is with preening himself.

While the game laughs at Tsao, it’s also desperately trying to convince you that bad guys can reform and become Good Guys by holding the Panda King up as an example. Sly is initially wary about the King (you know, because he helped murder Sly’s father). But the King slowly wins over various members of the team by helping them on missions. This all culminates in his mission helping Sly, before which he gives his reflection a pep talk. Here, the game sends you into a dialogue mini-game where the Panda King has to calm his fractured psyche by getting his Yin and Yang sides on the same page (it’s like the writers saw a NatGeo special on Taoism while high, and then insisted on plugging it here). Panda Yin wants to utilize Sly’s help to free their daughter, and thinks Sly is actually an ok dude. Panda Yang thinks Sly is an uppity jerk who disgraced them and that they don’t need his help. The game sides with Panda Yin, shockingly, and tasks you with convincing Panda Yang of Panda Yin’s point of view with preprogrammed options. The winning line of reasoning states that “Cooper is a teacher of humility” and that that quality is somehow spiritually useful to them for its own sake.

Just to recap, Sly is the kind of guy who cites his bloodline as evidence of his existential superiority over the Panda King, and pisses on him for being upwardly mobile. Sly is the kind of guy who routinely involves his best friends in harebrained schemes to achieve his inherently selfish ends, without ever really asking them how he could lend them a hand with their problems. Sly is the kind of guy who gets angry with cops when they put him in jail for breaking the law. If Sly taught anybody humility, it sure as hell wasn’t by example, and so Panda King’s insistence that he can learn humility from Sly reeks of kowtowing. The game says the Panda King can be a Good Guy…if only he learns his place and stays there, at the feet of Sly Cooper, thieving royalty.

All of this confused classist nonsense culminates in the heist, where the Gang not only rescue Jing King, but also seek to ruin Tsao by robbing him of his family treasures. In the process of doing this, the Gang destroy Tsao’s ancestral temple and take his most prized heirloom treasures, and the game portrays his justifiable outrage as evil and megalomaniacal. Remember, the first game had you traveling all over the globe to ruin and brutalize five people in order to recover one such prized heirloom of the Cooper family that was stolen. But doing the same thing to Tsao is all well and good, because he is a Bad Dude. In anger, he even yells at Cooper, “Hear me Cooper, my lineage surpasses yours in every way!” It is at this moment that the game, in an attempt to simultaneously erase and embrace its own blatant elitism, has its protagonist utter the single most inane line of the series, “It’s not about the family name pal…it’s what you do with it!”

Are you kidding me? That’s the best you can come up with?

What does Cooper mean by this statement, precisely? What should one do with his family name? How have Cooper and Tsao, respectively, measured up to that standard? Who knows? The game never answers any of these questions explicitly. In fact, there are only two explicit reasons we are given to hate Tsao, one of which is the kidnapping of women. But the reason that is placed front and center, that is repeated more often than anything else, is the fact that Tsao believes his lineage is superior to Cooper’s. It is this apparent megalomania that really shows that Tsao is evil. Tsao is a villain because he failed to learn his place, at Cooper’s feet, as the Panda King did.

All of the troubling politics thus far coalesce neatly into the final level of this game, when we return to Dr. M’s island. After many further hijinks, aimed at infiltrating M’s fortress, Cooper, Bentley, and Murray manage to crack open the heavily guarded door to the Cooper Vault, and Sly insists that the three enter the front door of the vault together, having gone on so many adventures. But the game treats this touching gesture of friendship with cold, hard cynicism. The very minute the three friends step into the Vault, there is another door that only Sly is agile enough to even access, and so he is rescued by circumstance from having to actually follow through on his offer to his friends. As if the narrative had to make it clearer that it didn’t think Sly’s friends are worth enough to access his heritage, Bentley voices the sentiment explicitly, “…this place was built for you [Sly]. We’ll hold down the fort here.”

While Sly is making his way through the caverns of the Cooper Vault, in which the Cooper Clan seems to have stored a non-negligible percentage of global GDP in the form of gold, jewels, and art, that second statement in the above quote proves prophetic. Bentley immediately doubles back on the sentiment he expressed by asking Murray, “Do you ever feel like you’re playing second fiddle to Sly? Like he treats us as sidekicks?” Murray doesn’t see it that way, responding, “…we’re all in it together!” And all at once, Bentley starts unraveling the games politics in one fell swoop, “Sure, we’re all here, but are we equal? Who went into the Vault? Sly. By himself.” But Bentley never gets to finish his point, because it is at that moment that the Vault, now opened, is invaded by Dr. M’s goons. Murray succinctly summarizes the situation and their options, “Think of it this way, Bentley. If it were you in that vault, and Sly and I were out here, what would he do?” Bentley responds with the only answer, “Stop these thugs and protect his friend.”

It’s as if the game only had Bentley raise these questions in order to swat them aside. The crushing thing is that Bentley had almost discerned the game’s politics from within the game itself. Bentley, the brains of the team, was approaching a fundamental truth in his world. Sly doesn’t treat Bentley and Murray as sidekicks…but the game sure does. The narrative certainly does not see Bentley and Murray, let alone any other characters, as equal to Sly. Sly went into the Vault, alone, because this is HIS story, and nobody else’s. And it’s the moment Bentley begins to realize and articulate this that the game puts him back in his place with a sentimental appeal to friendship. Besides, Bentley isn’t in the Vault to question the politics of the situation, he’s there to “hold down the fort.” This is Sly’s show after all, and Bentley’s not even on the fiddle. He’s on the drum set at the back of the stage.

You were SO CLOSE!!

And it turns out that the villainous Dr. M voices exactly the same critique Bentley just brushed up against. Dr. M follows his goons into the cave and reveals that he was the brains of Cooper’s father’s gang, much like Bentley is the brains for the modern Cooper Gang. Once you learn this information, Dr. M tries to build a bridge with Bentley, “…I know the pain you suffer working under your inferior.” The inferior in this sentence is Sly, and we know from Tsao’s example what that means about Dr. M’s character. Of course Bentley refutes this logic. It doesn’t matter that Bentley organizes the heists, does all the research, does his own R&D for the Gang, and in general vastly outstrips the rest of the Gang in terms of hours dedicated to the Gang’s success, because the Cooper Gang has one thing…”brotherhood.”

Dr. M scoffs at this, “Brotherhood? That’s just what he wants you to think. It’s a tool to keep you in line!” Dr. M is right about the nature of the tool, but he’s wrong about who’s holding it. It’s the narrative, not Sly, that insists on relegating Bentley to not-even-on-the-fiddle status. But Bentley has been blinded by his own vapid appeals to friendship. The game has decided he’s not worthy to bask in Sly’s heritage. Only His Highness the royal heir can do that. When Dr. M makes a move to enter the Vault proper, even Bentley says so, “That haul is for Coopers only!” Dr. M pragmatically replies, “Maybe it’s time for men such as you and I to change all that.” Dr. M insists that the work he put in as the brains of the old Cooper Gang make him worthy of the Cooper fortune his work contributed to…and the game, in it’s infinite wisdom, is absolutely certain that this basic act of self-respect makes him a megalomaniac. How dare he think he’s worthy of Sly’s fortune!? He’s not part of the bloodline!!

In the end, like every Big Bad before him, Dr. M tries to kill Sly because (SURPRISE!!) he hates Sly’s father, and by extension, Sly’s bloodline. After they fight, there’s a short scene where Sly and Dr. M discuss how, despite Sly’s maniacal obsession with his lineage, that he’s just an individual, and Dr. M can’t blame Sly for the fact that Sly’s father was, apparently, a dick. In the process of reminiscing, the comparisons between Dr. M/Sly’s father and Bentley/Sly come to a head, with Sly insisting that he would risk his life for his friends. The problem with that is that the game has rescued Sly from including his friends meaningfully as equal partners in the story. Saying he’d risk his life for them is just the game’s way of showing Sly is a good person without actually making him do anything to assert, by action, how much he values his friends.

And the game makes it known exactly how much Sly’s friends are worth without him after Dr. M is defeated. Sly manages, through faked amnesia (long story), to run away with Inspector Carmelita Fox, leaving his friends behind. In the aftermath of his escape, Bentley narrates the epilogue, explaining that, “Without Sly as our leader, for the first time we each had to step out on our own. A difficult thing, we’d been together ever since we met at the orphanage.” In other words, Bentley and Murray finally strike out on their own, as individuals separated from Sly’s legacy…except not at all. Murray goes into stocked-van racing, driving the Cooper van with Sly’s raccoon-faced logo on the side. The game refuses to let Murray have his own unique identity.

But what happens to Bentley is even more insulting. You see, Sly left Bentley and Murray an enormous trove of treasure he managed to evacuate from the Cooper Vault before leaving his friends behind. So what does Bentley do with their newfound wealth? Does he spend it on his own dreams? Not at all! Instead, he builds another, much higher tech Cooper Vault to bury the treasure in.

The treasure really only served to show how generous Sly was. The game never had any intention of validating Bentley’s worth by insisting he deserved a cut of Sly’s legacy. And the game makes this even clearer in the final frames of the epilogue, where you see Bentley writing his narrated words, “So while this might be the end of our adventures, it could be the start of something even bigger!” The hitch? He’s writing those words in Sly’s family book, from the first game! The game refuses to allow for any possibility that Sly’s friends might have any identity beyond upholding his royal legacy, or that they are worthy of being equal partners in that legacy. Even after Sly is gone, living his own life, his friends are not allowed to the same. The game won’t let them, because, as we’ve seen throughout this series, anybody who thinks they have an inherently meaningful identity outside of Cooper’s lineage, or who merely insists that they deserve more than they were born into, is a villain…and Sly Cooper will always be there to put them in their place.