It’s easy to see that comics do not enjoy the prestige or financial backing of the fine arts. It’s harder to justify why not. Many arguments are primarily emotional– the textbook Art Since 1900 discusses comics with thinly veiled disgust, and a cartoonist or publisher can self-righteously reply that art world acceptance is something owed to them. Some argue that differing treatment is a matter of different histories. The broadsheet ancestor of comics branched off from the ‘fine art’ lineage centuries ago, but this ignores the rampant interbreeding of art and comics, and the intersection of their audiences, for the last fifty years. An alternative, manifold hypothesis is given by the prolific comics scholar Thierry Groensteen in his book, Un Objet culturel non identifie (An Unindentified Cultural Object, 2006). Groensteen proposes five ‘symbolic handicaps’ crucial to the devaluation of comics. Beaty offers an aggressive treatment of these in his book Comics Versus Art (2012):

“First, he argues that comics are a ‘bastard’ genre resulting from the ‘scandalous’ mixture of text and image; second, that they are intrinsically infantile and consumed by adults who are seeking to prolonge their adolescence; third, that comics are associated with one of the most degraded branches of the visual arts, caricature; fourth, that they have not been integrated into the development of the visual arts throughout the course of the twentieth century; and finally, that the images produced in comics do not command attention as a result of their multiplicity and tiny format.”

Beaty disregards the first two handicaps only in that they rely “heavily on the intersection of the form with pre-existing aesthetic discourses that had little to do with comics per se… “ Yet he only seriously considers handicap number four, comic’s segregated development from the contemporary art-world, as an obstacle to wider readership.

While this angle a deserves a book on its own, Groensteen’s third and fifth handicaps are worth a harder look. Beaty points out that comic’s relationship to caricature is used to elevate comics more than devalue them, but this association also creates a glass ceiling, where comics can not rise above the marginal place of caricature in the art-world. Beaty dismisses Groensteen’s last handicap, saying,

“Similarly, when Groensteen suggests that comics suffer because of their format, their small printed size and the multiplicity of images, it is difficult to accord this factor any great weight. Groensteen himself devotes very little attention to the suggestion and is not able to mount a particularly compelling case for it. While monumentality has been an important aspect of the visual arts for centuries, it does not seem to follow that small-formatted works have been particularly disparaged specifically for their size.”

Yet perhaps without realizing it, Beaty cites at least three major examples where a comic panels was magnififed and isolated from their sequence in order to elevate their source.

Comics Versus Art presents a thorough history of comic-centric art shows. One of the first major gallery shows dedicated exclusively to comics was held by SOCERLID (Societe civile d’etude et de recherché des literatures dessinees) in 1967 at Paris’ Musee des arts decoratifs, which is part of the Louvre. The show featured three sections on comic art, although the curators didn’t showcase any original strips or pages. Instead, they hung ektachromes and photographic enlargements of individual comic panels, with the coloring removed. The curators argued “thanks to the quality of the paper and clarity of the blacks and whites, the photographic enlargement makes it possible to free the comic strip from the small size that stifles it and to exhibit it in the usual dimensions of the works of art to which the public is accustomed.”

Many more gallery shows sidestep comic narrative altogether in favor of what the curators believe to be the form’s mosts substantial contribution to society—its characters. In a survey of several museum shows that drew inspiration, but did not include, comics, Beaty concludes, “these exhibitions indicated that it is the iconography of comics, rather than the formal—that is to say sequential—elements that is mostly commonly appropriated by artists influenced by comics.” The Institute for Contemporary Art’s 1987 show Comics Iconoclasm featured sections on cartooning technique as well as sequential storytelling, rare for most comics-centric gallery shows, yet both of these sections were dwarfed by the section on cartoon icons.

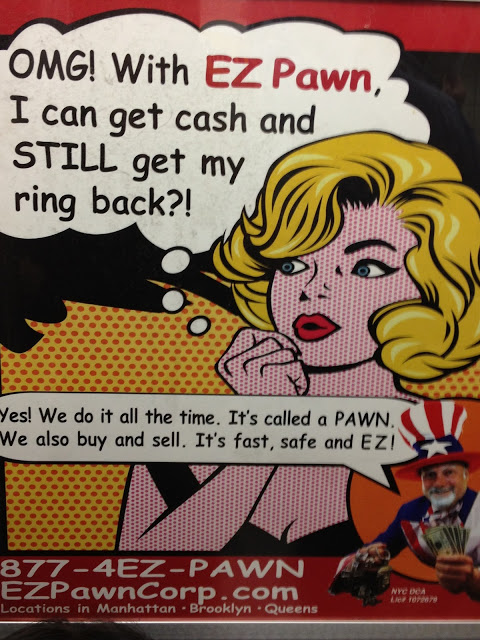

The legacy of Roy Lichtenstein and his comic panel appropriations, often accused of barring comic’s high-brow acceptance, could be the best example of all. Lichtenstein’s work has ensured immortality for the ‘look’ of mid-twentieth century romance and war comics. Museums adore and celebrate Lichtenstein’s accessible iconicity in their marketing, even as this look has been endlessly adopted by advertising. The look engulfs whatever meaning Lichtenstein has an artist, or his paintings have as individual works, and today the ben-day dot women function as stylistic, feminized stick figures. Yet this wouldn’t have happened without Lichtenstein’s blow-up treatment, and the strange prestige it accorded it.

Beaty documents related examples in the world of mainstream comics publishing. Maximum FF, a deluxe-edition book published in 2005 by Marvel Comics, was one telling attempt.

“An oversized hardcover with an elaborate fold-out dust jacket, Maximum FF is a 234-page version of the first issue of Fantastic Four, by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, originally published as a twenty-five-page comic book in 1961. Mosley and Sahre expanded the original work almost ten-fold by dramatically restructuring it: by disaggregating the individual panels and presenting them one per page, one per double-page spread, and even, on two occasions, as quadruple-page gatefolds.”

Beaty goes on to say that the ‘splash’ page and double-page spreads,

“…are particularly valued by collectors of original comic book art because they often present characters drawn on a larger scale than is typical for a comic book and, consequently, are more impressive when framed. For some collectors, the splash page and comic book cover are the most valuable parts of the comic because they are most akin to traditional gallery and museum aesthetics—they are not tainted with the sequentiality that is often held to define the comics form.”

Groensteen would agree with the idea that comics is tainted by its sequentiality, or at least sequentiality is not very relevant or attractive to most of society. Tellingly, the earliest definitions of comics focused on its use of recurring characters and speech bubbles than on its sequentiality—something Beaty recognizes in the first chapter of his book.

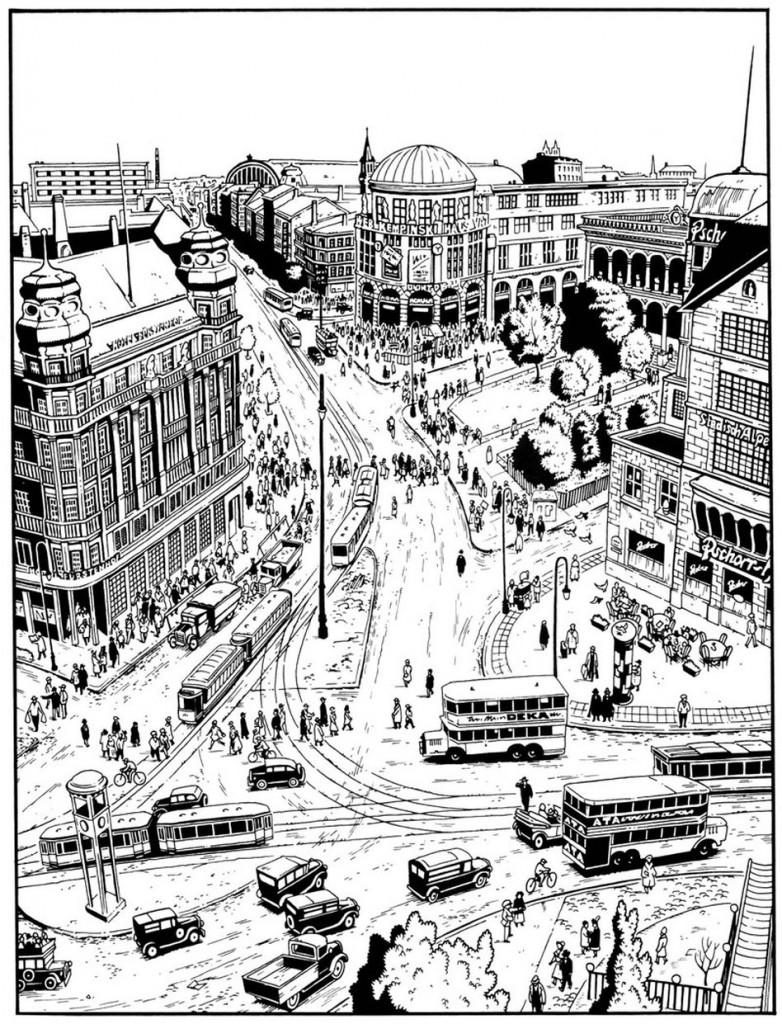

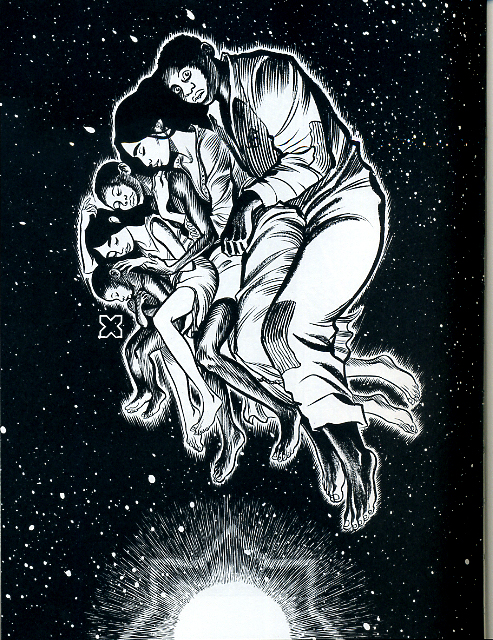

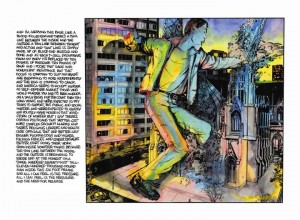

It’s worth wondering about the phenomenology of the splash page and double-page spread, and what happens when they are used in comic books. The splash page is a ubiquitous element of many comics, from American superhero books to manga to independent minicomics. It’s use isn’t random—splash pages most often introduce a story, establish the grandiosity of a setting, or monumentalize the climax of a single issue or narrative arc. The effect is always intended to be eye-catching, attention-grabbing, and big.

Steve Ditko and Stan Lee, Amazing Spider-Man, Issue #33

Rumiko Takahashi, Inuyasha, Book 1

Jason Lutes, Berlin, Volume 1

The splash page is a part of the vocabulary of comics, (or at least its grammar,) and some cartoonists play with or complicate the concept more than others. Within the limited scopes of alternative comics, a few recent examples come to mind. In Craig Thompson’s Habibi, (2011) (which I reviewed here,) a preponderance of splash pages marks the end of the book. Thompson’s loud pages erupt with obvious, mystical-religious imagery, asserting not only that an epic moment has been reached, but that moment is ever-present. The artwork grasps at transcendence, and the narrative, increasingly interrupted, begins to break down.

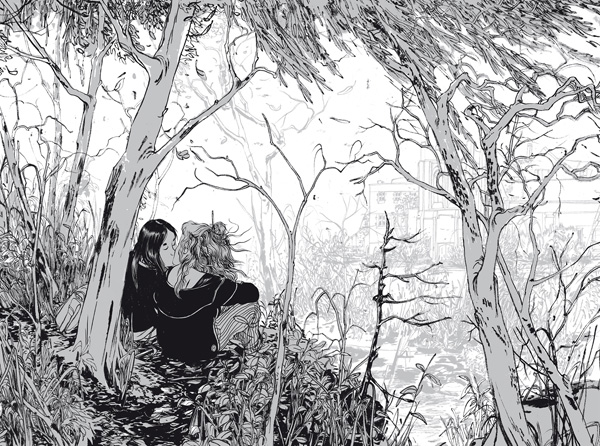

Skim, by Mariko and Jillian Tamaki, (2008), paradoxically uses splash pages to transition between scenes, layer impressions, and create a sense of passing time, even though only a single moment is presented. Both approaches use splash pages earnestly, but where Habibi’s splash-pages-on-steroids amplifies their stillness and power, Skim converts this potential energy into emotional movement.

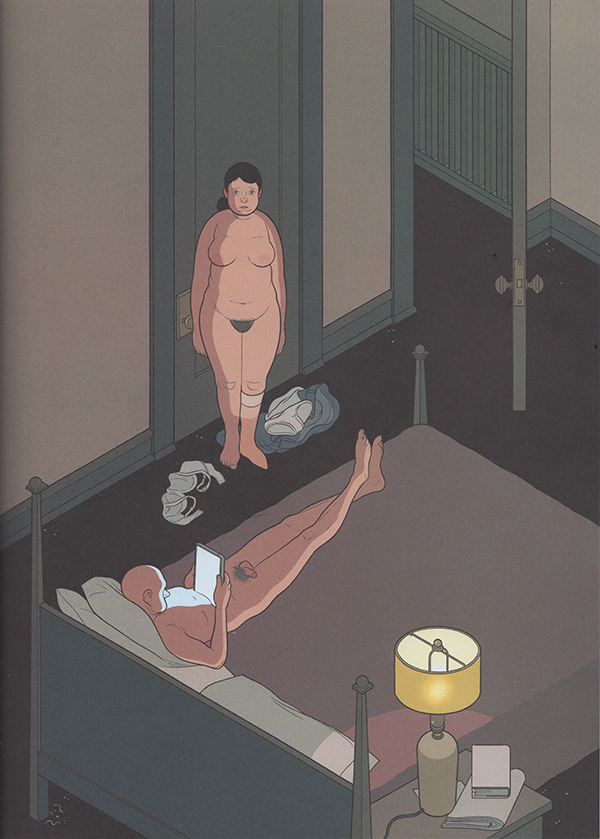

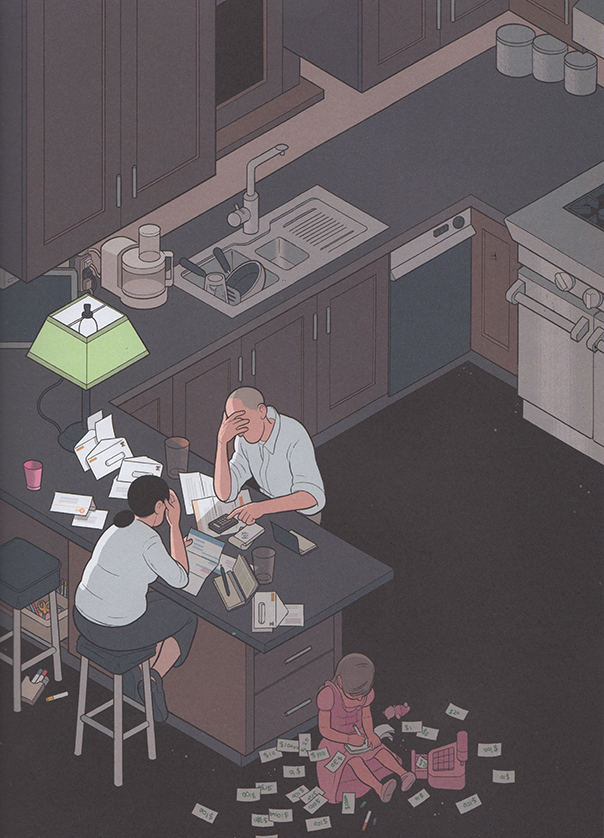

In Chris Ware’s Building Stories, (2012), the cartoonist ironizes the epic quality of the splash page by depicting banal moments in the life of his characters. However, the splash page has the last laugh, fostering a sort of ‘epicly banal’ or ‘very depressing’ feeling, which hasn’t escaped the notice of critics like Douglas Wolk. Perhaps Ware’s splash pages are better read as mislaid covers; they share the cheeky realism of his illustrations for The New Yorker, and one of these pages was featured as a ‘joke cover’ on the New Yorker site. It seems difficult to use the splash page insincerely– it transforms its content into something remarkable, whether the artist meant it to be read that way.

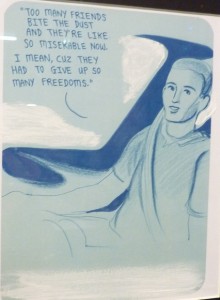

It’s funny that one of the most prominent and dramatic techniques in comic storytelling is one that makes a comic behave a little less sequential, fragmented, even hybrid-like. While captions and speech balloons are often present, they feel less like a competing element, especially in terms of scale, (aside from the author credits and copyright jargon jammed into some mainstream pages.) The splash page isn’t actively read as much as it is passively gazed upon, or absorbed, as if on a wall. That jump from reading to gazing is partially what makes experiencing a splash page feel profound. But only one moment can be presented, and there often isn’t much to figure out. The splash page is the opposite of the comics gutter, the space between the panels that contains the ‘unshown,’ and according to Scott McCloud, generates the medium’s storytelling power. While splash pages and individual panels are the easiest to display, a cartoonist’s panels and gutter transitions better capture the essence of a narrative work.

Its not surprising that the art-world and collectors, unsure of how to hang comics on a wall, would favor panels and pages that behave more like paintings. But is it possible to successfully bring comics narrative– small, printed, sequential and ambiguous– into a museum setting? Or is its special breed of profundity incompatible with what attendees expect from a gallery show? Outside of more people reading actual comics, (and how would they be convinced to do that?), is there a venue, or a kind of oration, that better matches the type of transcendence a comic book achieves, rather than what it reaches on one page or panel? As long as the gallery-show remains the standard by which high-brow acceptance is judged, discussion of what makes the comics medium work, (or even great,) will be locked onto their resemblance of fine art. Artists with greater technical skill will be rewarded most, despite the fact that the art world has bucked judgements of skill, chaining comics to a quaint nostalgia for draftsmanship. And severing panels from their original sources does not an art movement make– shows will remain an oddity, a fun, occasional diversion from looking at real art. Many people would not mind. Some readers will always need comics to act a little bit more like other things, in order to love them in those kinds of ways.