The question of comics’ status as an art-form might be irrelevant. Comics might never be accepted into the fold of institutional art, shown in galleries and supported by million dollar donors, yet they are en route to attaining a different kind of prestige. ‘Graphic novels’ are well-respected, recommended literature. Comic book franchises dominate pop culture, and comics studies are relatively well established in academia. Comics creators could still do with more money and credit, but it makes less and less sense for comic books and strips to aspire to the art industry’s pedestal. The complaint that most cartoonists demonstrate more talent than contemporary artists falls apart in the light that both are playing different games.

Film is a good example of this: there is an ‘art’ to filmmaking, and ‘art films,’ but film is not a genre of fine-art. Yet comic’s relationship to institutional art still remains largely unsketched. This is surprising, since the comparison between the two still inspires controversy, and they are not unrelated.

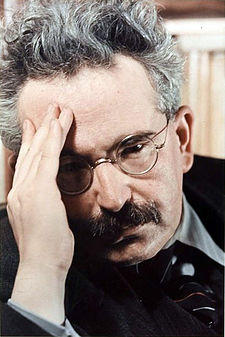

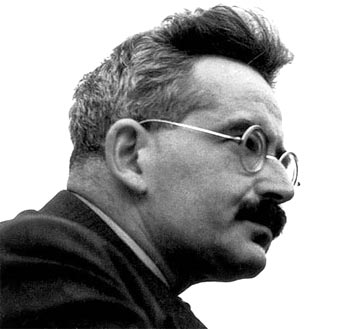

Walter Benjamin, a literary critic, philosopher and social critic, never intended to write about the nature of comics. He wouldn’t have been opposed to it: his insight and curiosity ranged from classic literature to popular illustration to chambermaid’s novels. One seminal essay, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,”* focuses on film and photography, but many of his arguments address the strangeness of another product of modern technology: the comic book. The essay was published in 1936, three years after the creation of the first comic books in the United States and Japan, and four years before his failed escape from Nazi Germany.

In “The Work of Art…,” Benjamin wrote about the implications of photography as an art form before it was widely considered one. He writes, “…commentators had earlier expended much fruitless ingenuity on the question of whether photography was an art—without asking the more fundamental question of whether the invention of photography had not transformed the entire character of art” (28). Benjamin devotes most of the essay to a discussion of film, which he understood as the natural evolution and greater manifestation of twentieth century technology. Unlike film and photography, comics lack the ubiquity and readership to change the nature of art, and as Benjamin argues, the nature of perception. Although, comics have made their own contributions.

Comics are as representative of the same shifts in the cultural landscape, and are descended from many of the same precursors as photography and film. Applying Benjamin’s arguments to comics hazards some guesses about the medium’s relationship to ‘high brow’ forms. It also suggests that comics’ fan community isn’t an accident, but an inextricable and inevitable part of the form.

- The Lineage of Comics

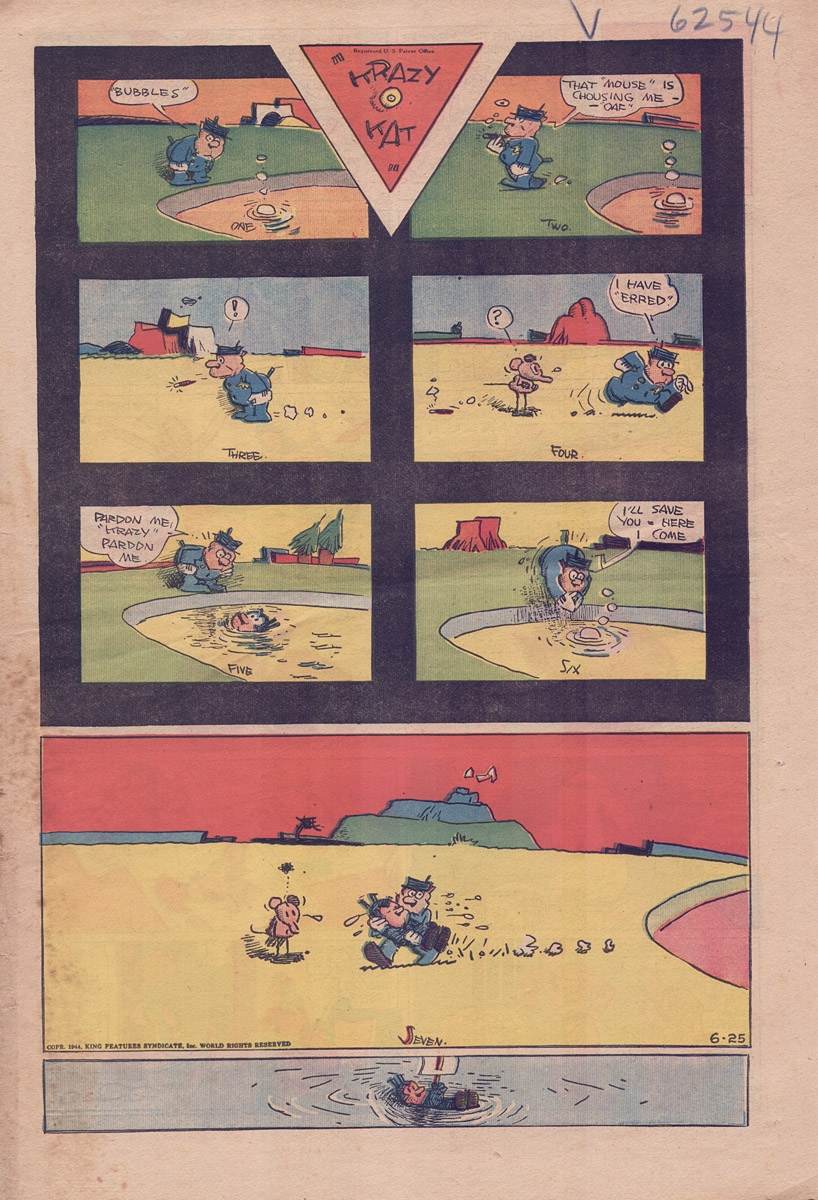

Benjamin traces the origin of photography all the way back to the woodblock. Woodprints were used both for books and broadsheets, or printed public announcements and stories. News and narratives were often conveyed with images alone, as the public was illiterate. Engraving and etching later replaced the ‘reportage’ use of woodblock prints—woodblock didn’t reclaim popularity until early modernists readopted it for its primitivism. Lithography then replaced metal plates, allowing for large numbers of copies to be published on a daily basis. With lithography, drawings could be transferred onto the printing stone. Before, prints had always looked like prints. You could tell there were multiple copies just by how it looked. Now, a newspaper illustration could resemble art that once could only be made and reproduced by hand. The scientific invention of photography usurped lithography, and finally made representation dependent on the eye alone. Illustrations in newspapers nearly became obsolete. As newspaper illustrations, photography and comics are distant cousins, both descendents of the broadsheet.

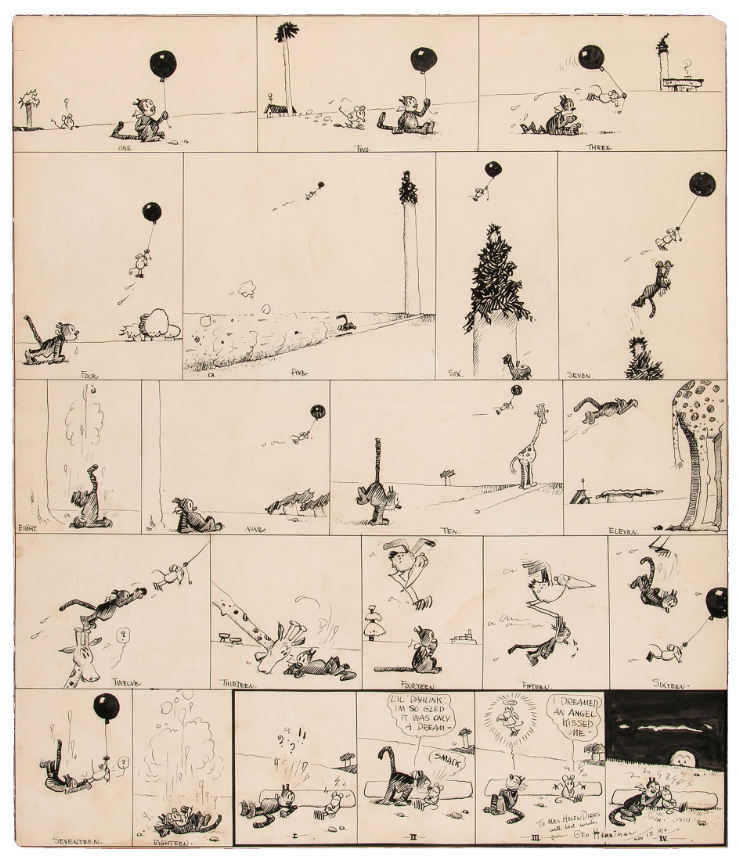

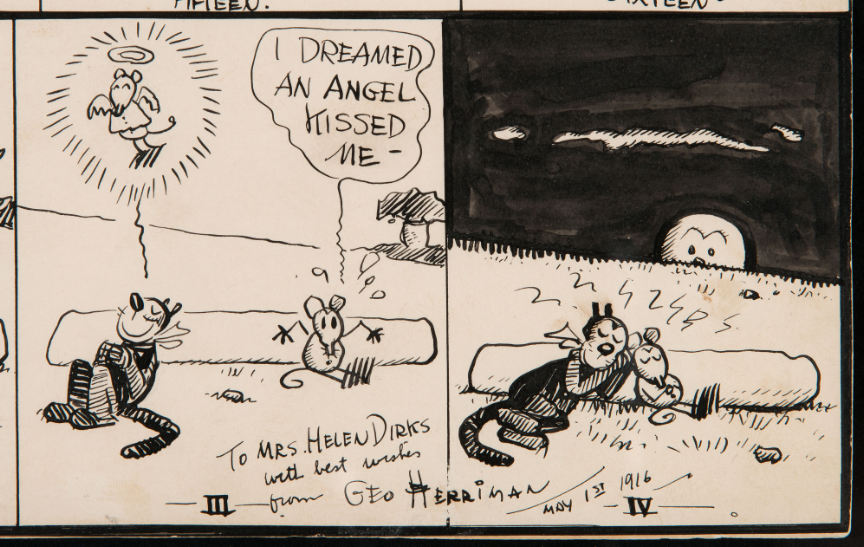

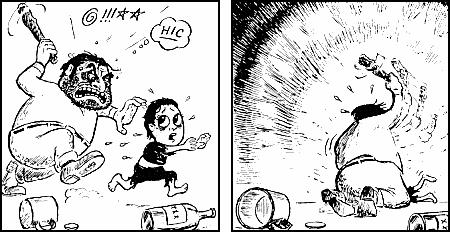

Film and photography shifted the way people could perceive things. For the first time, we knew how a horse’s feet fell when running, and could catch almost imperceptible changes in body language. Benjamin refers to this as “the optical unconscious.” Film can magnify the tiniest details, and can slow down or rewind actions—kinds of perception and visualization that hadn’t been available before. The invention of comic strips and books obviously wasn’t a scientific endeavor, relying on printing technologies already in play. In comparison, comics have given us a (perhaps) universal visual system to communicate speech, thought, movement and impact, but its a light-hearted system, and outside of a comic narrative, unsuited to serious expression.

- The Lack of an Unique Original

In his essay, Benjamin describes the degradation and fragmentation of the ‘original’ work of art through photographic reproduction, and the predominance of art forms that lack originals. This change was partly driven by the public’s desire to “overcome” an art work’s uniqueness and bring it closer to themselves, preferring accessible copies of the same work to a proliferation of small, one-of-a-kind creations. The proliferation of reproductions reduces the value of engaging with the original. We approach the Mona Lisa and it looks small and dark. After so many postcards, Uluru (Ayer’s Rock,) is only impressive for the first few minutes. We’ve seen it before. What once was a rare and location dependent experience now occurs wherever and whenever the consumer likes, and the reproduction is often cheap, sometimes disposable. This results in a detachment from the weight of tradition, and a loss of “aura.” Benjamin coined the term as “a strange tissue of space and time: the unique apparition of a distance, however near it may be. To follow with the eye…a mountain range on the horizon or a branch that casts its shadow on the beholder is to breathe the aura of those mountains, of that branch” (23). His theory parallels the belief in some cultures that photographing an object removes its soul.

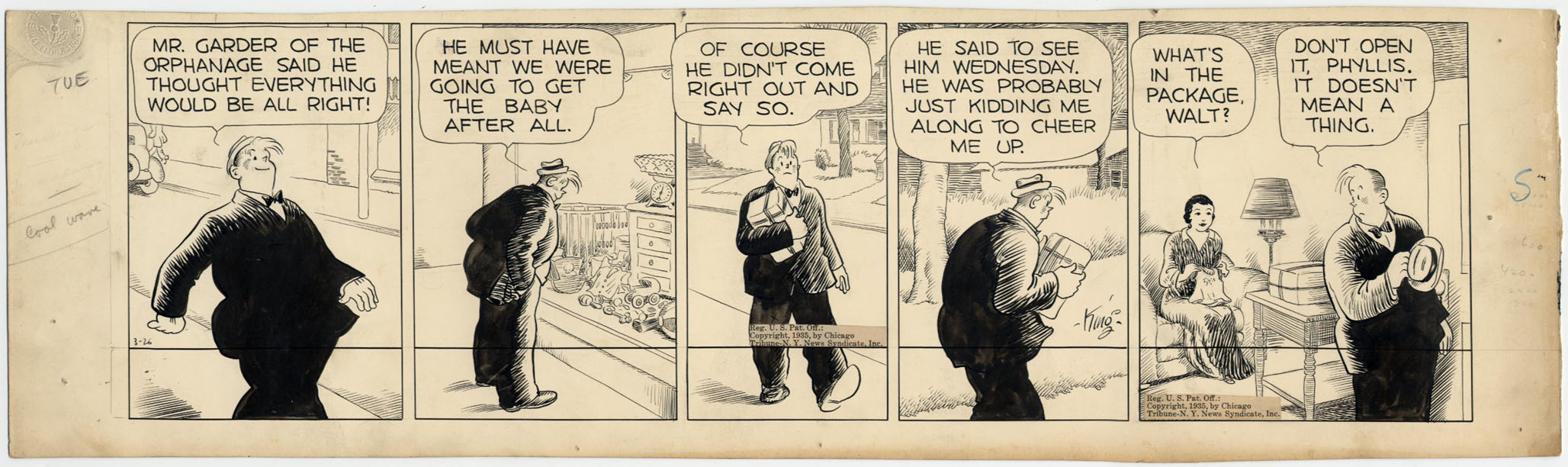

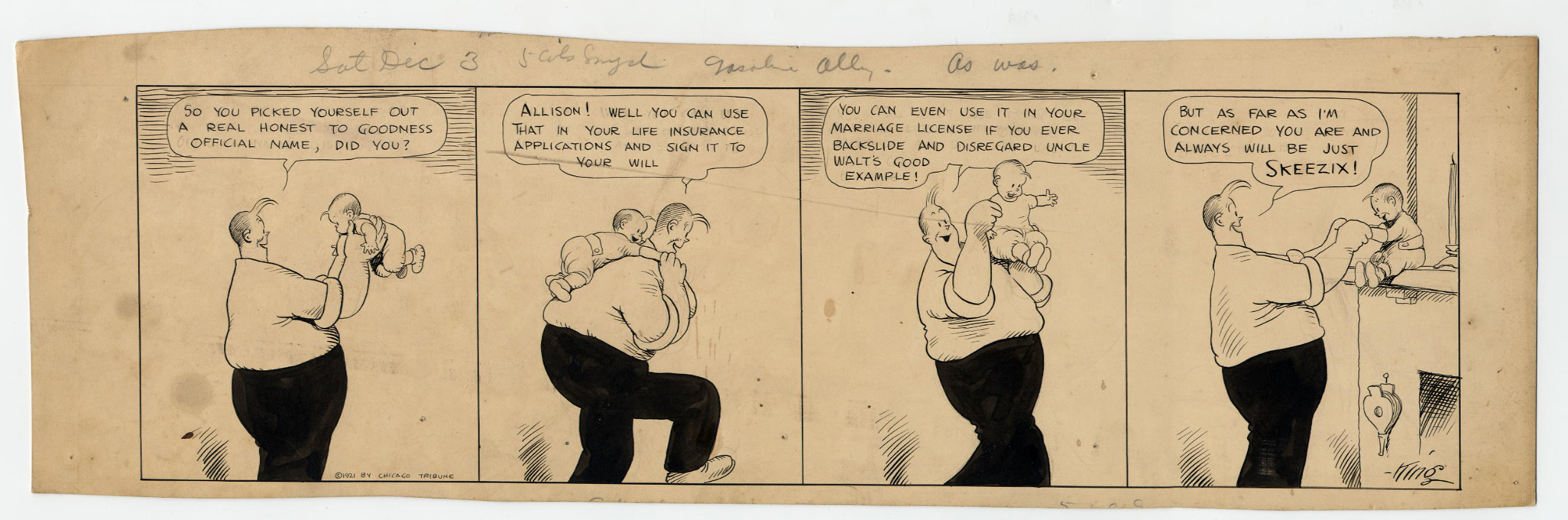

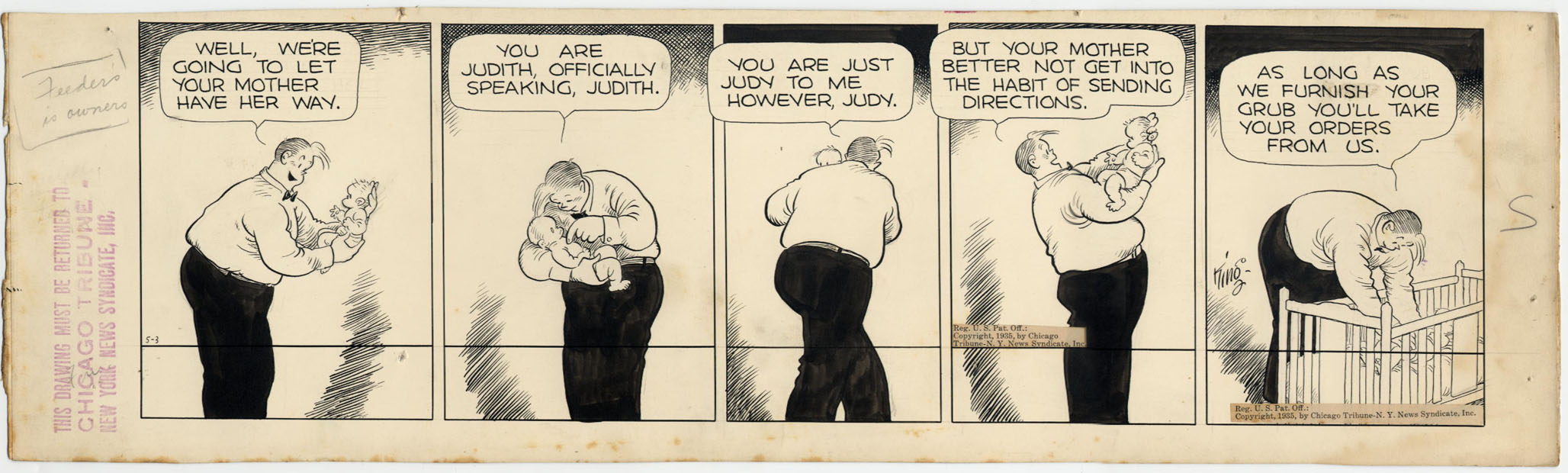

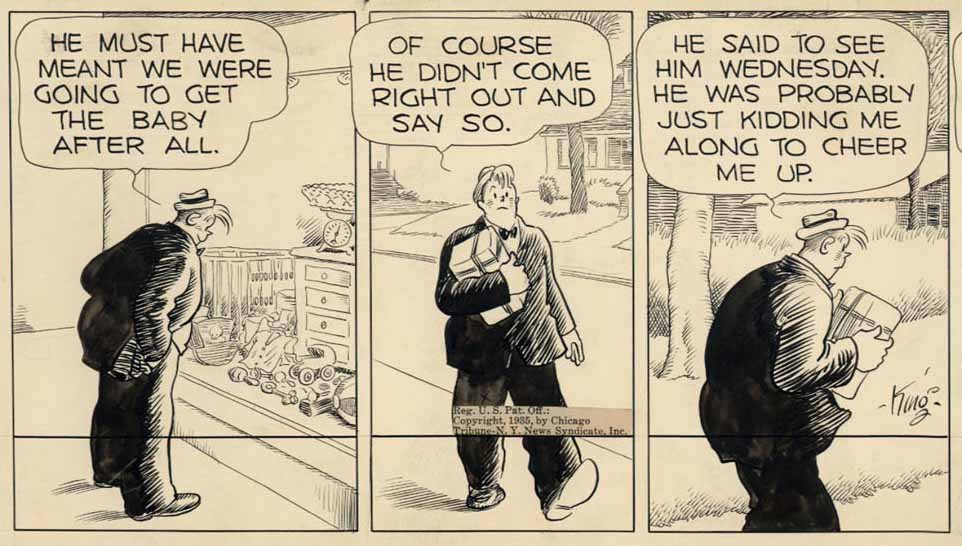

Comics, like all prints, have always lacked originals. The invention of lithography allowed them to appear hand-drawn, or resemble a work with an aura. Printmaking demands skill and artistry, but the vision of the printing press, cranking out copies is harder to romanticize than an illustrator bent over his board, drawing a single virtuosic stroke. The disposabililty of the comic strip and book resulted from the impulse to bring work closer to the reader, but the dynamic artwork and storytelling inspires the desire to become even closer than that. Yet it is impossible to behold an “original” comic, the source of all the multiples, and so its origin-point is scattered between the original artwork, the creators, the publisher, and the franchise.

3. Assemblage from Fragments

“Film is the first form whose artistic character is entirely determined by its reproducibility… The finished film is the exact antithesis of a work created in a single stroke. It is assembled from a very large number of images and image sequences that offer an array of choices to the editor; these images, moreover, can be improved in any desired way in the process leading from the initial take to the final cut” (30).

Comics amplify this when the nature of the visual itself can be redrawn. There is no actor’s performance to cut up and stitch together—the actor doesn’t exist in the first place. Then again, sometimes he does: artists like John Romita Sr. have admitted to copying panels from film stills, and photographic reference is often necessary. Comic’s reference to camera “angles” was doubtlessly borrowed from film. Some pages are collages, patched together from different sources. Sometimes older pages are cut up, for their images are reused on other pages. Finally, the process of reproduction manipulates the contrast and removes pencil lines. The color and the lettering is often added on a copy, not on the linework—no original comic ‘page’ exists, and the penciler’s work is eradicated by an ink tracing.

This lack of aura is compensated by the growth of the cult of celebrity. Following Benjamin’s reasoning, aficionados would latch onto the human figure, the creator, the character, the story’s universe, and the best possible copy, as they are unable to form a relationship to an original work.

4. Fan-Issues and The Cult of Celebrity

“Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” is a fabulously dated, Marxist text. Benjamin was unable to predict the ubiquity of cameras and their every day use. “In photography, exhibition value begins to drive back cult value on all fronts… It falls back to a last entrenchment: the human countenance” (27). For Benjamin, this last entrenchment is the ownership of pictures of the dead, rather than a general obsession with taking pictures of each other.

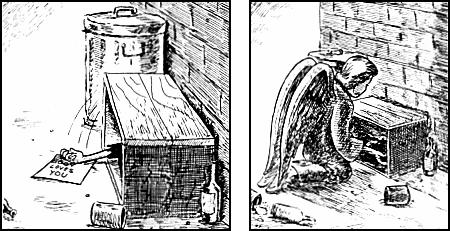

In film and comics, where there is no original copy to behold, the fan must pursue other avenues to become closer to the work. Autographs and other ‘indexes’ of the creator’s presence command incredible value. In some cases, the creators would command more interest than the art-work, creating celebrities. In the case of narrative work, popular characters would be expanded into franchises. Fan communities would grow out of this Sisyphean approach of authenticity, and fan-community concerns would be articulations of this perturbation.

The nature of comics, and mainstream comic’s current dominance of pop culture, dictate a different set of fan-community issues than those of film. And for that matter, art. Celebrity-dom has taken over fine-art, where historic masters command higher prices than ever, and contemporary artists are most valued when shaping themselves into new art-heroes. There continue to be more reproductions, digitally and on more distinct kinds of merchandise, than ever before.

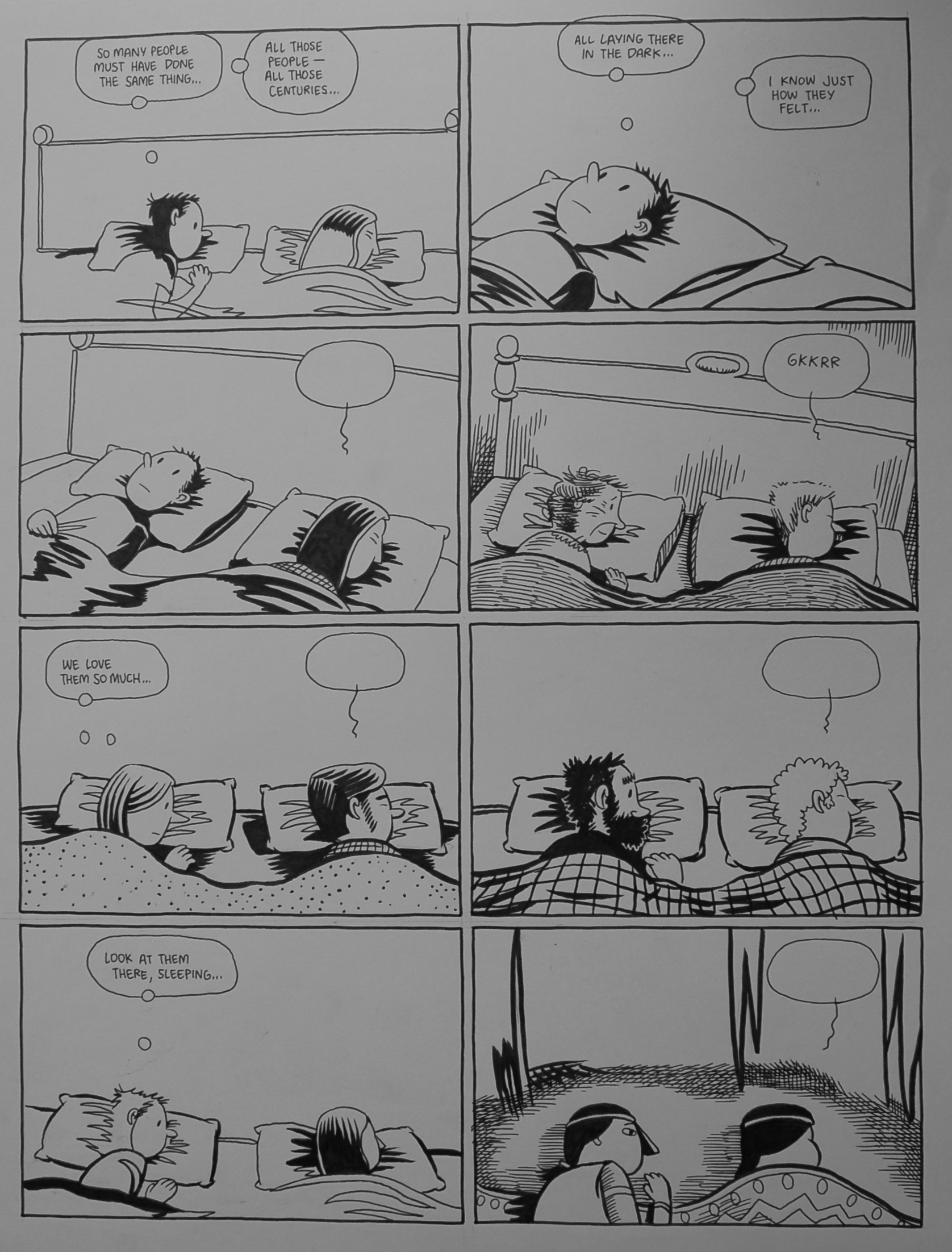

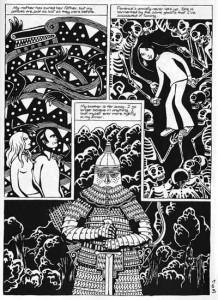

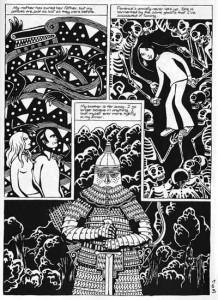

Benjamin believes that the social function of film is to reconcile humanity to technology’s fragmenting of experience—that meaning survives ‘the apparatus.’ By their nature, comics might be more escapism than reconciliation. There is no actor to reclaim his identity, no real world with a stolen ‘aura.’ Comics are created using technology we are comfortable with—they are nostalgic. This is not a bad thing—comics succeed at expressing the subjective, surreal and fantastical with a naturalness and integration that film’s special effects may never achieve. The complicated diagesis of mainstream comics is one of the most fascinating narrative systems in human history. Fantasies are as revealing as our visions of reality, which can be equally fantastical.

from Epileptic, by David B

But fantasies are also manipulative. Benjamin anticipates the loss of aura with an almost reckless happiness—as awed and appreciative as he is of aura, he believes it is used to protect class interests. If people can resist the urge to keep looking for aura where it doesn’t exist, we can move on to nobler work. Consumer capitalism would have us chase the rainbow of “authenticity,” becoming better and better consumers. “Not only does the cult of the movie star, [fostered by the money of the film industry,] preserve that magic of the personality which has long been no more than the putrid magic of its own commodity character, but its counterpart, the cult of the audience, reinforces the corruption by which fascism is seeking to supplant the class consciousness of the masses” (33).

*The quotes pulled from “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” are pulled from another translation (that I use as my travel copy. This translation can be found in The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility And Other Writings on Media (Belknap Harvard, 2008). I’d recommend reading the more orthodox translations in Illuminations or Reflections : Essays, Aphorisms, Autobiographical Writings (Schoken, 1986). There’s a link above to a digital copy, but its a less-recognized translation.